With growing activity and innovation around token-based network models, builders are wondering how to distinguish different types of tokens — and which might be the best choice for their business. At the same time, both consumers and policy makers are trying to better understand the roles and risks of blockchain tokens in applications.

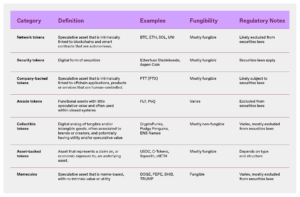

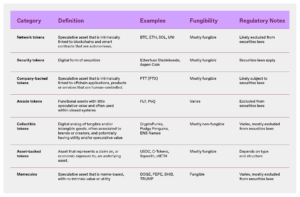

To help organize the conversation, we present definitions, examples, and a framework for understanding the seven categories of tokens we see entrepreneurs building with most often: network tokens, security tokens, company-backed tokens, arcade tokens, collectible tokens, asset-backed tokens, and memecoins. We outline them in more detail below.

A quick refresher: Tokens and their characteristics

Fundamentally, tokens enable true digital ownership.

More precisely, a blockchain is a decentralized computer composed of a network of individual computers maintaining shared ledgers — effectively, a “computer in the sky.” Tokens are data records on those ledgers that can track quantities, permissions, and other metadata. Critically, these data records can only be changed according to the rules encoded on the blockchain, and those rules can be used to grant enforceable rights.

Beneath this precision, there’s a lot of detail that has implications for design, functionality, value, and risk: Because tokens are embedded in software, they can be programmed to represent pretty much anything — any digital form or record of property. That means tokens can be designed to be digital stores of value like Bitcoin, productive and consumptive assets like Ether, collectibles like digital trading cards and game items, payment stablecoins like USDC, and even digitized shares of stock.

Some tokens provide holders with various rights — voting rights or economic rights, for example — while others simply enable the use of a product or network service. Some tokens are transferable among users, and others are not. And some tokens are fungible in the sense that all units are equivalent (like dollar bills), while others are non-fungible, in the sense that they represent unique individual assets (unique, like a trading card, or even the Mona Lisa).

These design choices matter because they dictate whether a token might be a good store of value or medium of exchange; whether it might be a productive asset with innate functional and/or economic value; or whether it’s inherently valueless. The characteristics of a given token also dictate how it might be treated under applicable laws.

So, whether you’re building a blockchain-based project, investing in tokens, or simply using them as a consumer, it’s essential to know what to look for. It’s important not to confuse, for instance, memecoins with network tokens. The remainder of this article aims to help clear up the confusion.

Tokens types

Network tokens

Network tokens are intrinsically linked to, and derive their value from, the programmatic functioning of a blockchain or smart contract protocol.

Network tokens often have embedded utility; they may be used for network operations, to form consensus, to coordinate protocol upgrades, or to incentivize network actions. The networks to which these tokens relate also often (and in most cases should) contain economic mechanisms that drive the value of the token. These include programmatic buybacks, dividends, and other changes to the total token supply via token creation (“faucets”) or burning (“sinks”) to introduce inflationary and deflationary pressures in service of the network.

Network tokens can have trust dependencies that are similar to both commodities and securities. Recognizing this, both the SEC’s 2019 Framework and FIT21 provided for network tokens to be excluded from U.S. securities laws when those trust dependencies are mitigated through decentralization of the underlying network. The core essence of decentralization is that the system can operate without human control (a person, company, or management team).

Network tokens are best used to bootstrap the creation of new networks, distribute ownership or control of a network to its users, and/or ensure the network can self-fund its own continuous and secure operation. Examples of network tokens include DOGE, Bitcoin’s BTC, Ethereum’s ETH, Solana’s SOL, and Uniswap’s UNI. In the context of smart contract protocols like Uniswap and Aave, network tokens are also sometimes called “protocol tokens” or “app tokens.”

Security tokens

Security tokens represent the digital form of a security, which could be in a traditional form – like a share in a company or a corporate bond – or might take on specialized characteristics, such as providing a profits interest in an LLC, a share in an athlete’s future earnings, or even securitized rights to future payments of litigation settlements.

Securities typically grant the holder a defined right, title, or interest, and their issuers usually have unilateral power to affect or structure the risk of the asset. With the SEC expected to modernize securities laws to permit onchain transactions, the number and types of securities that will be tokenized will likely grow, which could bring efficiencies and enhanced liquidity to securities markets. But even as the category grows, digital securities will remain subject to securities laws in the U.S.

Security tokens have been used for raising capital for business ventures. Examples of security tokens include Etherfuse Stablebonds and Aspen Coin, a fractional ownership interest in the St. Regis Aspen Resort.

Company-backed tokens

Company-backed tokens are intrinsically linked to, and derive value from, an offchain application, product, or service operated by a company (or other centralized organization).

Like network tokens, company-backed tokens may make use of blockchains and smart contracts (e.g., to facilitate payments). But because they primarily relate to offchain operations rather than ownership of a network, a company may unilaterally control their issuance, utility, and value. Like arcade tokens (described below), company-backed tokens often have their own embedded utility. Unlike arcade tokens, company-backed tokens are speculative.

Given these characteristics — even though company-backed tokens don’t grant the holder a defined right, title, or interest like a traditional security — they have trust dependencies that are similar to securities: Their value is inherently dependent upon a system that is controlled by a person, company or management team. As a result, although company-backed tokens are not securities per se, transactions in company-backed tokens, when they attract investment, are likely to be subject to U.S. securities laws.

Company-backed tokens may become a legitimate category. However, they have historically mostly been used in the U.S. to unlawfully circumvent securities laws — attracting investment in applications, products, or services controlled by a company, potentially acting as a proxy for an equity interest or profits interest in that company. Examples of company-backed tokens include FTT, which functioned as a profits interest in FTX’s exchange, or a hypothetical cloud service provider issuing tokens that enable holders to access the cloud services as well as receive a portion of the onchain revenue derived from such services. Meanwhile, BNB is an example of a company-backed token that evolved into a network token with the launch of the Binance Smart Chain. Company-backed tokens are sometimes referred to as “startup tokens,” or, given their link to an offchain application, “app tokens.”

Arcade tokens

Arcade tokens provide utility within a system and that are not intended for investment purposes. Arcade tokens often function as currencies within a digital economy. Examples include digital gold in a game, loyalty points within a membership program, or redeemable credits for digital products and services.

Importantly, arcade tokens are distinguishable from security tokens, network tokens, and company-backed tokens because they are specifically designed to dissuade speculation. For instance, these tokens may have uncapped supplies (meaning an unlimited number can be minted) and/or limited transferability; they may expire or lose value if unused, or they may only have monetary value and utility within the system in which they are issued. Most importantly, they do not offer, promise, or imply financial returns. Given their unsuitability as investment products, arcade tokens are generally excluded from U.S. securities laws.

Arcade tokens are best used as currencies within digital economies, where the issuer derives economic benefit from controlling the monetary policy (i.e., acting as the central bank) of that digital economy and maintaining a steady token value – as opposed to benefiting from the appreciation in token value. Examples include FLY, the loyalty and payment token of the Blackbird restaurant network. Another example is Pocketful of Quarters, an in-game asset that received no action relief from the SEC in 2019. Robux and Start Alliance Points have not yet been tokenized but otherwise encapsulate the concept of arcade tokens well. Arcade tokens are also sometimes called “utility tokens,” “loyalty tokens,” or “points.”

Collectible tokens

Collectible tokens derive value, utility, or significance from being a record of ownership of a tangible or intangible good. For instance, a collectible token may be a digital analog or representation of a work of art, a musical composition, or a literary work; a collectible or merchandise, like a ticket stub from a concert; membership in a club or community; or an asset in a game or metaverse, like a digital sword or plot of metaverse land.

These tokens are typically non-fungible and often have utility. For example, a collectible token may function as a license or ticket to an event; could be used in a video game (like that sword); or could provide ownership rights with respect to intellectual property. Because collectible tokens typically relate to a finished work or product, and don’t depend on third party efforts, they are generally excluded from U.S. securities laws.

Collectible tokens are best used to convey ownership of tangible or intangible goods. Many, although not all, “NFT” products fall into this category. Examples include NFTs that convey ownership of digital art or other media; profile pictures (“pfps”) like CryptoPunks and Bored Apes, as well as other virtual fashion and branded goods; game items; and account records or identifiers such as ENS domains.

Some collectible tokens are directly associated with physical products, either to provide a digital extension of the physical product experience, like with Pudgy Penguins toys and Generative Goods collectible cards; or to provide a digital representation of a physical good that is easier to track and/or exchange, as with NFT event tickets and BAXUS’s vaulted liquor NFTs.

Asset-backed tokens

Asset-backed tokens derive their value from a claim on, or economic exposure to, one or more underlying assets. These underlying assets may include real-world assets (e.g., commodities, fiat currency, or securities) or digital assets (e.g., cryptocurrencies or liquidity pool interests).

Asset-backed tokens may be fully or partially collateralized and can serve different purposes: acting as stores of value, hedging instruments, or onchain financial primitives. Unlike collectible tokens, which derive value from ownership of a unique good (like digital art, in-game items, or event tickets), asset-backed tokens function more like financial instruments, deriving value from their collateral, price-pegging mechanisms, or rights to redemption. The regulatory treatment of asset-backed tokens, however, depends on their structure and use. Some, like fiat-backed stablecoins, are generally excluded from U.S. securities laws. Others, like certain derivative tokens, may be subject to securities or commodities regulations if they represent investment contracts or futures-like instruments.

There are many use cases for asset-backed tokens, including:

- stablecoins, which are pegged to a currency or asset;

- derivative tokens, which provide synthetic exposure to underlying assets or financial positions;

- liquidity provider (LP) tokens, which represent claims on pooled assets in decentralized finance (DeFi) protocols; and

- deposit receipt tokens, which represent staked or escrowed assets.

Examples include USDC (a fiat-backed stablecoin), Compound’s C-tokens (an LP token), Lido’s stETH (a liquid staking token), and OPYN’s Squeeth (a derivative token tracking ETH’s price).

Memecoins

Memecoins are tokens without intrinsic utility or value, often tied to an internet meme or community-driven movement, and not fundamentally tied to a network, company, or application.

Memecoins’ prices are driven purely by speculation and associated market forces, which makes them highly susceptible to manipulation. Their central features are their lack of intrinsic purpose (if they had a purpose, they would no longer be memecoins), lack of utility, and their resulting zero-sum nature and volatility. Memecoins are generally excluded from U.S. securities laws, although they are still subject to anti-fraud and market manipulation laws.

Examples include PEPE, SHIB, and TRUMP.

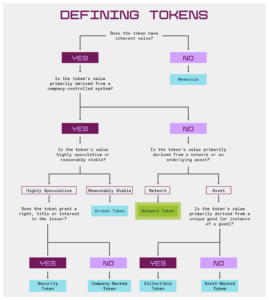

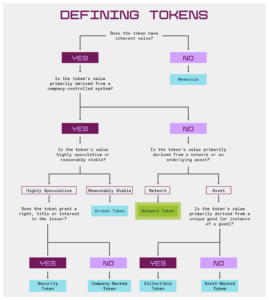

Not every token will fit neatly within one of these categories — entrepreneurs are regularly iterating and experimenting with new models. For instance, social and reputation tokens may function more like arcade tokens if they aren’t investable, or could function more like company-backed tokens if they’re controlled by a centralized issuer. Tokens can also evolve from one category to another as their characteristics are changed or new features are added, making classification difficult.

But the defining characteristic that delineates these categories is the expected source of value accrual. A flowchart helps illustrate this point:

***

Acknowledgements: We’d like to thank Chris Dixon, Tim Roughgarden, and Bill Hinman for their helpful comments; and Tim Sullivan for his editing.

***

Miles Jennings is General Counsel of a16z crypto, where he advises the firm and its portfolio companies on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs, and state and federal securities laws.

Scott Duke Kominers is the Sarofim-Rock Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, a Faculty Affiliate of the Harvard Department of Economics, and a Research Partner at a16z crypto. He also advises a number of companies on web3 strategy, as well as marketplace and incentive design; for further disclosures, see his website. He’s also the coauthor of The Everything Token: How NFTs and Web3 Will Transform the Way We Buy, Sell, and Create.

Eddy Lazzarin is the chief technology officer for a16z crypto. He oversees the engineering, research, and security teams, which support the investing process and collaborate with portfolio companies to build the future of the internet.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.