What if the greatest breakthroughs in human history weren’t new inventions, but the simple removal of friction? We are trained to look for the next revolutionary product. We almost always overlook the invisible, boring standards that allow thousands of new products to exist.

This is a story about that hidden architecture. It’s about why the battle for the future isn’t about building a better thing — it’s about agreeing on the rules that let everything connect.

It’s a battle that repeats in every era, and today it’s being waged over the operating system for human ambition itself: money.

The most dangerous move isn’t falling behind on technology. The most dangerous move is to accept a “modern” solution that’s just a prettier cage.

The beginning

Our story begins not with an invention, but with a maddening, costly, and completely unnecessary stop.

In 1885, a passenger traveling across England — say, from London to Wales — would arrive at the station in Gloucester, disembark, and find herself stranded. Her journey was not over, but her train’s was. To continue, she would have to navigate a chaotic platform, haul her luggage to a separate station, and buy a new ticket for a different company’s train, one that ran on tracks just a few inches wider.

Nearby, a merchant might watch in despair as his cargo of fragile pottery was unloaded from one car and manually reloaded onto another, the cost of breakage and delay eating into any potential profit.

This was the daily, maddening reality of a closed system. In 19th-century Britain and America, railways were a fragmented patchwork of private lines, each with its own incompatible track gauge. It was a failure of coordination that held entire economies captive, levying a hidden tax on every person and every piece of cargo.

Then, over a single, frantic weekend in 1886, thousands of workers across the American South set out to fix the impossible. In a near-miraculous feat of coordination, they manually adjusted 13,000 miles of track to a national standard. By Monday morning, trains rolled uninterrupted from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. The result was immediate: Traffic rose 20% almost overnight. They chose a two-day sprint of relentless work to build a century of frictionless progress.

This chaotic, costly, and ultimately necessary act of standardization is not a historical curiosity. It is the central, repeating drama of human progress. In every era, we face the same fundamental battle: a war between the seductive, profitable, and orderly nature of closed systems and the chaotic, innovative, and explosive potential of open ones.

Timeless patterns

This pattern is timeless, defining everything from the dusty, physical routes of the Silk Road, to Roman units of measurement, to the invisible, digital architecture of the cloud we use daily.

If the logic of openness has been known for millennia, why do we keep forgetting it and rebuilding walled gardens?

Because fragmentation isn’t just an accident, it’s a business model. The allure of closed systems is rational and powerful. It’s about control, profit, and speed to market.

But while a closed system may scale rapidly — assuming it can convince others to join and avoid failure — that very design inevitably concentrates market power in the hands of its architect. That power leads to an irresistible temptation: not just to shape the system, but to extract most of the value for themselves. It comes down to a simple paradox: Everyone wants an open standard, as long as it’s their standard. Why cooperate when you can own the junction?

Whether it’s a 19th-century railway baron defending his proprietary gauge, a tech giant controlling its closed social graph, or a fintech designing a CorpChain — a blockchain that is neither truly open nor permissionless — the playbook is the same. The owner retains the power to dictate the terms of engagement and capture a disproportionate share of the value created.

But while a closed system may scale rapidly ... that very design inevitably concentrates market power in the hands of its architect.

Closed systems also appeal to a deep-seated desire for order. They are environments where participants can be vetted, rules enforced, and outcomes planned and managed. Open, chaordic systems trade this engineered stability for a different prize: permissionless innovation. They are inherently unpredictable, and their very nature creates asymmetric outcomes — both massive new value and significant new risks.

The temptation, then, is to lock in a market, to build your kingdom in the belief that this control is the only path to a durable and profitable future. But this strategy fundamentally misunderstands the nature of innovation. It’s a fatal trade-off: In exchange for short-term profits, the architect of a closed system gives up the one thing that guarantees long-term survival: adaptability.

History’s verdict here is unambiguous. The very systems built for control, no matter how dominant they appear, are eventually out-innovated and overwhelmed by networks that choose to cooperate on the underlying standard, and then compete on the products.

The genius is the standard

Consider the chaos of global trade before the 1960s. For centuries, shipping was defined by “break-bulk cargo”: innumerable barrels, sacks, crates, and boxes loaded and unloaded by hand. Every port was a unique logistical nightmare. Ships spent more time docked than at sea.

Then a trucker from North Carolina, Malcolm McLean, reframed the problem. He realized the problem wasn’t the ships or the cranes—it was the lack of a common interface. His solution, the simple, standardized steel shipping container, looked incremental but was revolutionary.

That one standard — a box that could move seamlessly from truck to train to ship — was an open protocol. It allowed for competition to thrive on top of the new rail. Suddenly, shipping companies, truck lines, and port operators could all innovate on their own piece of the puzzle, knowing it would connect to the whole. The cost of loading a ton of cargo fell by 97%, and global trade expanded more than sevenfold within two decades.

As The Economist put it, one boring box did more for globalization than 50 years of trade agreements combined.

The same principle revolutionized retail in the 1970s. Before the barcode, every checkout was manual, every store an island. Inventory was guesswork. There was no “universal language” for commerce.

The solution? The now-ubiquitous Universal Product Code (UPC).

At first, adoption stalled in a classic chicken-and-egg problem: Retailers wouldn’t buy the expensive scanners until products had the codes. Manufacturers wouldn’t print the codes until stores had the scanners.

But once the system hit a tipping point, the protocol turned retail into software. Suddenly, inventory wasn’t guesswork, it was a real-time data stream.

As The Economist put it, one boring box did more for globalization than 50 years of trade agreements combined.

The $17 billion in annual savings was, in fact, the least interesting part of the story. The most interesting part was the new clarity the system created. For the first time, early adopters could see it all: what to build, where to sell it, and what should come next. They didn’t just get more efficient; they built global supply chains on a scale the world had never seen.

This reveals a fundamental truth: The best product doesn’t win. The most vibrant ecosystem does. A universal interface is how you build one.

This brings us back to the central tension between open and closed — a tension that is as old as civilization, and one that has always presented two competing paths to success.

Standards by decree or standards by consensus

The first model is a top-down standard, imposed by a single power. When the Roman Empire rose, it didn’t just connect disparate regions; it inherited chaos. It faced a world of friction, a nightmare of incompatible parts — local roads, local currencies, local customs.

The Romans had a profound, modern insight: You cannot run an empire on chaos. You must first build its operating system. So they created a protocol. A standard for the entire known world. Every road was built to the same width and foundation. A uniform coinage allowed commerce to flow without friction.

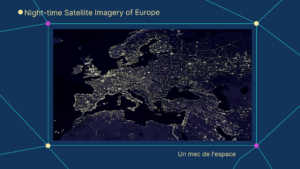

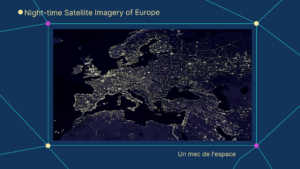

What began as a military project became the economic platform for an entire continent, collapsing the cost of transport and trade. The proof is etched onto the planet. Two millennia later, night-time satellite imagery of Europe still traces those ancient routes — a physical map of how coordination compounds value across millennia.

The second model is a bottom-up standard, which emerges from users, innovators, and misfits.

Two thousand years ago, even as the Romans were starting their standardization project, the Silk Road served as the prime example. Here’s the thing most people get wrong: It was never one road. It was an interlocking web of exchanges, an open system. And because it was open, no single ruler controlled it, and no gatekeeper could shut it down.

Kings tried to tax it. Robbers tried to raid it. Empires tried to wall it off. But the network was smarter than any single part — it just routed around them. It was alive.

The Silk Road was a protocol for trade. Standard weights and measures emerged not from decree, but from necessity. The network carried silk and spices, but its true exports were technology, ideas, and culture. It connected worlds.

Top-down standards are powerful, but they inevitably involve an empire — whether to create and enforce the standard or as a result of the standard’s succeeding. Bottom-up standards are resilient, but they are forged through sometimes painfully slow, decentralized experimentation and consensus.

This same dynamic — the fundamental tension between imposed design and emergent order — would come to define the digital age.

The early computer industry was a world of proprietary systems. Every machine was its own universe — from DEC to HP to the IBM mainframes. Software written for one wouldn’t work on any other.

Then, in 1981, IBM — the king of closed systems — made a fateful decision. To accelerate speed to market, they built their new personal computer with off-the-shelf parts and ended up licensing its beating heart from a little-known software startup from New Mexico: Microsoft.

Bill Gates’s masterful move was to retain the rights to license that operating system, MS-DOS, to everyone else. In a moment of historic irony, IBM had accidentally created one of the most influential open standards of our time: Wintel.

This set up a natural experiment, pitting Apple’s closed, vertically integrated model against the open Wintel ecosystem. The results were not even close. While Apple controlled every piece of hardware and software, the Wintel standard exploded. Dozens of hardware companies competed to build cheaper, faster machines, and developers could finally write a program once to run it everywhere.

Within less than a decade, the open PC platform dominated, capturing over 80% of the market. The lesson was brutal and absolute: An open ecosystem, by enabling a faster pace of hardware and software innovation, will almost always outpace a more closed, proprietary solution.

The internet became the ultimate test of this dynamic. At its dawn, incumbents bet on control. Proprietary portals like America Online, Apple eWorld, and Microsoft Network built walled gardens, attempting to curate — and monetize — the entire user experience.

On the other side was not a competing product but simply a set of open, ownerless rules: TCP/IP and HTTP.

It wasn’t a fair fight. It was a complete annihilation. The open protocols simply routed around the walls, just as the Silk Road had routed around empires.

Why? Because you cannot curate the future.

It wasn't a fair fight. It was a complete annihilation. The open protocols simply routed around the walls, just as the Silk Road had routed around empires.

Permissionless innovation on an open standard will always create exponentially more value. The result was one of the largest productivity expansions in history, unleashing over $2.1 trillion in value in the US alone, and driving 21% of GDP growth in advanced economies in just 5 years.

The most powerful wins, however, are often the most unexpected. When Linux appeared, it was dismissed by industry experts as a “toy.” It wasn’t as polished as Windows; it wasn’t an enterprise-grade product. It was, they said, a hobbyist project.

But this critique fundamentally missed the point. The power of Linux wasn’t in the features of version one: It was in its new, open architecture.

That “toy” with the penguin mascot now runs 90% of the cloud and 100% of the world’s top 500 supercomputers, creating an estimated $8.8 trillion in value. The open standard became so dominant that its greatest enemy, Microsoft — a company that once famously called it a “cancer” — was forced to embrace it. The open standard, in the end, was simply too powerful to compete with.

The last, big closed network: Money

Today, our financial system looks exactly like the 19th-century railways. It is a fragmented patchwork of closed, proprietary networks. A handful of institutions run the tollbooths of everyday payments, collecting what amounts to a private tax on the economy with every swipe, tap, or wire. Like a constant background radiation, this friction invisibly erodes business margins through a cascade of fees—totaling over $187 billion in merchant fees in 2024 alone—all cleverly disguised by the brilliant marketing scheme of consumer rewards.

We are all, in effect, still standing on that platform in Gloucester, hauling our baggage to the next platform, watching our delicate wares get manhandled by porters, paying a hidden tax on our own ambition.

We have seen attempts to fix this. In the 1960s, the credit card industry faced its own coordination failure. When Bank of America tried to scale its credit card network unilaterally, its losses ballooned. The turning point came when Dee Hock realized no single bank could own the standard. They created a cooperative — Visa. The principle was simple: Cooperate on the infrastructure, compete on the products.

More recently, India built a public open protocol called the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). By creating a neutral, shared rail for digital payments, India cut transaction costs to near zero. In just a few years, UPI grew to handle 18 billion transactions a month. That’s nearly 50% of all real-time, global transactions… in one single system. Moreover, once payments became a solved, shared layer, entrepreneurs built better credit, lending, and commerce applications on top.

These consortia or public-sector-led models are the modern equivalent of the credit card network and the Roman roads — top-down, imposed standards. But permissionless blockchain networks and cryptocurrencies have introduced a third possibility: the Silk Road model. A network for value that is not owned by a company, a cooperative, or even a single nation-state. A neutral, emergent, and open protocol for money itself.

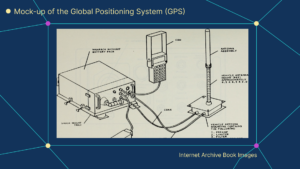

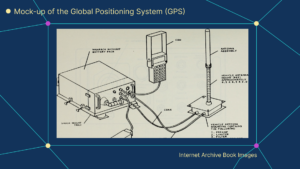

The best analogy for its potential impact is the GPS. This system wasn’t built for the public: It was a closed, top-secret tool built by the US military, for the US military. It was designed for one thing: strategic advantage and control.

And then, in the 1980s, the government did something that changed the world. They flipped a switch. And they gave the signal away — to everyone, for free. They effectively handed humanity a superpower with no idea what would be unleashed. They couldn’t have predicted Google Maps, Uber, or precision agriculture. They didn’t have to.

Nobody had to ask permission. Nobody had to launch a satellite. The foundation was simply there — an open, public protocol for location. This was the true gift: the freedom to build. An entire generation of entrepreneurs built new industries on top, focused on creating value, not on coordinating on the infrastructure or licensing it from an incumbent.

An open financial infrastructure will play this role. It’s about providing a foundation as open and as neutral as a GPS signal — so that you can be the architect. So you have the freedom to build, the freedom to compete on your product, not to waste time rebuilding the plumbing.

But this is not the future the incumbents are selling. They are coming to you with a great story about a “CorpChain.” They will tell you it’s frontier technology. They will tell you it’s purpose-built for payments. But a CorpChain isn’t the future. It’s just a higher wall. A cage painted gold with partnership incentives. It is a system with their rails and their rules. A system where your organization will never have root access. A system where you are a tenant, not an architect.

To choose the wall — the “CorpChain” model — is to accept the friction that quietly, invisibly grinds progress to a halt. It is to accept the tax that the present levies on our future. The cost, in lost opportunity and human potential, is immense.

The value unlocked by a truly open network will always be infinitely greater than the profit captured by a closed one.

This, then, is the choice — the same one faced by the railway barons, the shipping magnates, and the internet’s architects. We can continue to build our own incompatible gauges, profiting from the moats that keep us apart. Or we can do the hard, necessary work of coordination.

The economic lesson is unambiguous: The value unlocked by a truly open network will always be infinitely greater than the profit captured by a closed one.

It all comes down to the simplest question: Do we build higher walls or open roads?

History only remembers one of those choices.

It remembers the road builders.

***

Christian Catalini is the co-founder of Lightspark and the MIT Cryptoeconomics Lab.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.