Over the past month, we’ve seen two major exploits on closely related systems: Balancer’s Composable Stable Pools and Yearn’s yETH. The details differ — the math and code paths aren’t identical — but the shape of the failures is strikingly similar: subtle numerical behavior at the edge of precision, exploited through highly sophisticated sequences of transactions.

The Balancer exploit alone siphoned more than $120 million. The shock was amplified because the targeted contracts had been operating for years — considered “battle‑tested” and safe by many. Just a few weeks later, yETH suffered a separate exploit with a different immediate root cause but the same underlying pattern: tiny numerical errors becoming material under adversarially engineered conditions.

When two such incidents land back-to-back, it’s no longer just about a single bug or protocol. It suggests a broader class of numerical vulnerabilities that our standard defenses don’t fully address.

In this post, we use the Balancer incident as a concrete case study. We distill the core mechanics and outline methodologies to prevent similar failures, from pool-favorable rounding and virtual liquidity to precision math and, ultimately, runtime enforcement of invariants. We argue that, especially in light of recent events, runtime enforcement should be treated as a first-class design requirement for systems that rely on complex numerical behavior.

We don’t usually cover exploits in depth, but this time it’s worth sharing our analysis. We hope this helps the community better understand and secure their protocols.

A recurring pattern: Subtle numerical edge cases

Both recent incidents share a common pattern:

- Under normal conditions, tiny rounding or precision errors are economically irrelevant.

- Under carefully engineered, adversarial conditions, those same errors dominate the outcome.

- Attackers can deliberately drive the system into these edge conditions and then extract value.

This is not unique to a single design. Any protocol that combines complex math, numerical methods, and composability is exposed to this class of risk.

In what follows, we’ll walk through the Balancer exploit as a concrete running example of this pattern, and then show how the same defensive ideas — especially runtime enforcement — apply more broadly, including to the yETH incident and future designs.

Balancer exploit: Mechanics

Let’s unpack how a seemingly minor rounding quirk cascaded into a large-scale exploit.

Small rounding errors: Not a big deal — until liquidity gets tiny

The immediate cause most people point to is rounding in the “wrong” direction — think “1 wei” off. In a well‑funded pool, though, being off by one unit on a normal trade is negligible — the gas would cost more than any drip‑feed benefit.

What really matters isn’t just the direction of the rounding error but its relative magnitude compared to the resulting value. An error that’s imperceptible in a deep pool can dominate the outcome in a thin one.

Where it becomes dangerous is when pool liquidity is extremely small. Imagine a pool with reserves of (10 wei, 10 wei). If a rounding error lets a trader take 2 wei instead of 1, that extra wei shifts reserves by 10%, materially distorting price. (This is a simplified illustration — the actual math is subtler.)

So if an attacker can make liquidity momentarily small, a directionally bad rounding error can warp reserve ratios enough to manipulate price and extract value.

But in a healthy decentralized pool, temporarily collapsing liquidity is hard. You’d need to compromise many LPs to coordinate exits across them.

How temporary low liquidity became feasible

One scenario where it does become feasible is when LP tokens can be arbitrarily minted and borrowed, or flash-loaned. In that case, an attacker could effectively borrow LP tokens, perform a liquidity exit to shrink the pool, exploit a rounding‑driven price distortion, then restore liquidity and repay at a lower LP token value.

In Balancer’s Composable Stable Pool, two design features combined to enable an LP-flashloan effect:

- Batch swaps with aggregated settlement. Instead of settling each leg immediately, the system nets balances at the end.

- LP mint/burn treated as token swaps, which means they can now participate in batch swaps just like ordinary trades.

If you “exit liquidity” early in the batch and “add liquidity” at the end, you’ve effectively obtained a flash loan of LP tokens for the duration of the batch.

With liquidity temporarily pushed down, the attacker could then leverage directional rounding to skew the reserve ratio and manipulate price. (We’ve omitted the detailed arithmetic here — see other write-ups for a full walkthrough.)

The combination — not rounding alone — was the crux.

This pattern — economically negligible error under normal conditions, but dominant under adversarially induced edge conditions — is exactly what we see in the yETH incident too, even though the specific formulas and code paths differ.

From attack to defense

With the mechanics understood, let’s look at defenses — first, a quick recap of baseline mitigations and where they fall short, then runtime enforcement techniques that push defenses further.

Baseline defenses

Start with foundational measures.

1. Pool-favorable rounding

This directly addresses the root cause of the Balancer incident. But it’s not always trivial: Complex math may require maintaining both “round up” and “round down” variants across code paths, and determining which direction favors the pool can vary by context. As DeFi math grows more intricate, airtight directional rounding becomes harder.

Moreover, “pool-favorable” rounding isn’t free of side effects. Because it systematically tilts outcomes against traders, attackers can sometimes exploit these rounding behaviors to extract value from other users rather than the pool itself — ERC4626 vault “inflation attacks” are a good example of this dynamic. In other words, making rounding always favor the pool doesn’t necessarily eliminate exploitability — it may simply shift who bears the precision loss.

2. Virtual liquidity

One way to mitigate low-liquidity fragility is to introduce virtual reserve offsets that favor the protocol and keep liquidity calculations numerically stable. This approach helps maintain a minimum effective depth even when real reserves thin out.

Another, simpler variant is to seed each pool with a non-trivial amount of initial liquidity that remains permanently locked. It achieves a similar stabilizing effect at minimal cost — negligible in most cases, though it can add up if pools are created automatically at large scale.

Both methods strengthen precision and stability under thin conditions, but they trade simplicity for either added math complexity or mild capital lock-up.

Enforcing high-precision fixed-point arithmetic

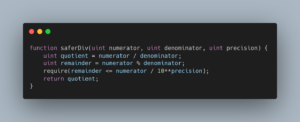

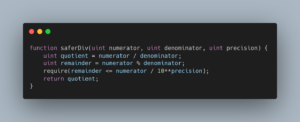

Though relatively untested, it may be reasonable to enforce precision on the division operation itself. This would involve measuring the output of the division operation and ensuring it was above a specified precision threshold. By doing this, protocols could ensure all critical rounding operations are precise enough that all rounding errors become mathematically negligible.

Numerical errors in DeFi protocols, after the adoption of safe math as the default, are rounding errors. Rounding errors arise from one operation — division. So how can we ensure that a division introduces less than a certain fraction of error? We check the remainder.

Illustrative pseudocode

Why this condition checks precision loss

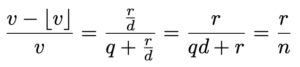

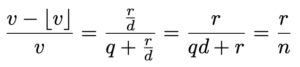

Mathematically, any division with numerator n, denominator d, quotient q, and remainder r can be written as n = q × d + r, where 0 ≤ r < d.

The real (mathematical) division result v is n / d = q + r / d, while the integer division result (as performed in Solidity) is ⌊v⌋ = q.

The relative precision loss from rounding down is therefore:

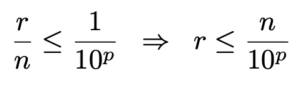

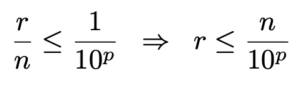

We want this loss to be less than a chosen precision threshold, for example ≤ 1/10^p.

That gives:

Hence, the check `require(remainder <= numerator / 10**precision)` enforces exactly this condition — it guarantees that the relative precision loss of the division is smaller than 1/10^p.

If the remainder is too large relative to the numerator, the operation reverts, ensuring all divisions that affect protocol state maintain at least the specified precision.

Limitation

One limitation of this approach is that it only bounds the precision loss for a single division.

In iterative or compounding calculations — for example, computing (1 + r)^n — small rounding errors can accumulate over multiple steps, eventually exceeding the precision threshold even if each individual operation is within bounds.

Addressing this would require tracking cumulative precision loss across the entire computation path, which is non-trivial and adds overhead.

Caveats and tradeoffs

This kind of runtime enforcement is great for safety — it stops weird behaviors before they happen — but it can also go too far.

If the condition is too strict, liveness issues can develop: Harmless transactions might revert just because they fall slightly outside the bounds. Once that happens, funds can get stuck.

To avoid that, make sure your enforcement thresholds aren’t tighter than they need to be. And as a backup, consider using upgradable contracts or admin-controlled enforcement toggle so you can lift the restriction if a fund-lock ever occurs.

Even with these caveats, enforcing precision on critical operations directly targets the “subtle numerical behavior under edge conditions” pattern we’ve just seen recur in two separate exploits.

Runtime assertions of security-critical invariants

When mathematical complexity or compounded precision loss makes it difficult to fully control rounding behavior — as in the case of accumulated errors across multiple operations — a final line of defense is to encode protocol invariants as runtime assertions. If an operation violates an invariant, it should revert immediately.

Crucially, this applies across the incidents: Although the exact formulas differ, in each case a core economic invariant was broken during value extraction. If that invariant had been explicitly encoded and enforced at runtime, the exploit path would have been blocked, regardless of the specific arithmetic quirk exploited.

In case of AMMs, two core properties should hold:

1. Total liquidity should never decrease (except for liquidity exits).

For constant‑product markets, as an example, this means k = x * y stays constant (hence the name) or increases slightly as fees accrue (and partly due to pool-favorable rounding). More generally: The pool’s total value should not shrink under normal (non-exit) operations.

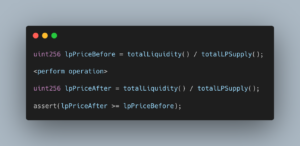

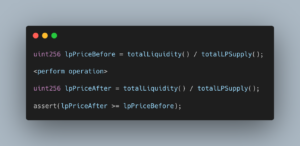

2. LP token value should not decrease.

That is, “total liquidity / total LP supply” should never go down as a result of any operation — even after a liquidity exit.

Every major AMM exploit ultimately violates one of these properties.

Of course, formally verifying these properties is ideal but often impractical for complex math. (In Balancer’s case, the formal verification didn’t capture these particular properties.) When compile-time proofs aren’t feasible, enforcing invariants at runtime can serve as a robust safety net.

Illustrative pseudocode for runtime enforcement:

This approach — known as runtime enforcement or runtime verification — has long existed in traditional software engineering and is overdue for broader adoption in DeFi.

Ask auditors to help identify security-critical properties and encode as many as possible as in-code assertions. You won’t catch everything, but you’ll block an entire class of exploits — including ones rooted in entirely new classes of vulnerabilities that have yet to be discovered — so long as any such attack would require breaking an invariant you enforce at runtime.

That said, the same caution applies here as before: While runtime enforcement is powerful for safety, overly strict invariants can introduce liveness issues — benign transactions reverting even when no real risk exists. To avoid locking funds or disrupting normal pool operation, invariants must be derived from rigorous analysis and implemented faithfully, then tested extensively. And as a fallback, consider making the enforcement logic configurable, so that if a liveness or fund-lock issue ever arises, the restriction can be relaxed or temporarily lifted.

***

The recent incidents showed how subtle numerical instability can turn into real vulnerabilities — and how the conditions that make them exploitable are hard to detect in advance.

Runtime enforcement of numerical precision and security-critical invariants provides a complementary — and increasingly necessary — last line of defense: a mechanism that ensures that even if an unforeseen mathematical subtlety slips through, the protocol will still reject any states that violate core economic properties.

By pairing numerical hygiene with runtime-enforced invariants, we can build DeFi systems that remain correct and resilient even in adversarial conditions — including ones we haven’t yet seen.

We’re also exploring a community effort to catalog runtime-checkable security properties for major DeFi designs — and we’d welcome anyone interested in helping push this work forward.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investment-list/.

The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures/ for additional important information.