Table of contents

- Rating methodology

- Making the grade: Summary of our analysis

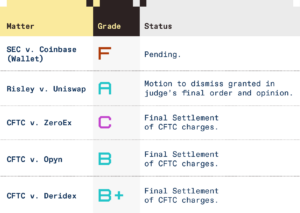

- Our enforcement action report card

- Matter: SEC v. Coinbase (Wallet)

- Matter: Risley v. Uniswap

- Matter: CFTC v. ZeroEx

- Matter: CFTC v. Opyn

- Matter: CFTC v. Deridex

Recent significant enforcement actions and court rulings demonstrate how different U.S. government actors view web3 regulation. While these actions may foreshadow how web3 will be regulated absent new legislation, they can also inform us about how new legislation could be tailored to appropriately regulate web3 to satisfy policy goals and provide a path for the industry to flourish in the United States.

As a result, we thought it would be helpful to examine, contextualize, and rate these actions – specifically, those involving Coinbase (Wallet), Uniswap, ZeroEx, OPYN, and Deridex – based on our “Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols’‘ framework (RANP). In particular, we examine whether the actions appropriately target business activity rather than software and its developers – the key tenet of RANP – and we assess them based on their adherence to RANP, as well as their application of existing laws. Overall, they are generally consistent with RANP’s focus on businesses rather than software, but do differ in their application of existing laws. This leaves us with far a more optimistic outlook than prevailing industry outlook about the current U.S. regulatory landscape.

As noted in part four of RANP, the methodology we use for assessing how existing regulation or new legislation should apply to a web3 project begins with an examination of the nature of the project’s underlying software protocol and whether it potentially implicates regulated activity. Where a protocol implicates regulated activity, we analyze the appropriate level of regulatory intervention or oversight (or liability) for specific applications referencing that protocol.

As we discussed in part two of RANP, even where a web3 protocol facilitates activity that would be regulated in a centralized context, a government’s or agency’s regulatory priorities should always balance the tradeoffs of additional regulation. In general, the government should not infringe individuals’ freedom to publish open source software. Instead, governments should constrain their regulatory focus on business-related activities undertaken in their jurisdiction, including the use of new technology to facilitate illicit activity or evade existing regulation.

We assess a protocol’s nature by determining if it is: (1) open source, (2) decentralized, (3) autonomous, (4) standardized, (5) censorship resistant, and (6) permissionless. Regulations that recognize the importance of these characteristics, and incentivize protocols to adopt them, should result in protocols that foster an open, free, and credibly neutral internet. This is, in fact, how the current base layer of the current internet is designed and how governments have viewed accountability of the web’s use. Where protocols demonstrate these characteristics, it curtails their potential use for regulatory arbitrage, for instance, by centralized businesses seeking to evade regulation by using smart contracts deployed to a blockchain they control.

In our case studies (which you can read in full) we evaluate each protocol against these criteria based upon the allegations of the relevant regulator (without taking a view whether the allegations were factually accurate), general industry knowledge, and the findings of the presiding judge presiding.

The second step of our analysis requires an assessment of what the appropriate risk and level of regulation should be for the application or business using the protocol based upon characteristics of the application or business. We’re guided by the rubric we established for centralized and decentralized exchanges in part four of RANP. The application of regulation or assignment of liability in our examples are only appropriate to the extent they relate to and address the risks posed by the application’s or business’s characteristics.

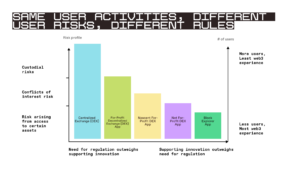

In the actions that implicated existing regulations, we assess whether the extension of such regulations to web3 makes sense in the context of RANP or if better tailored regulation is necessary given the unique characteristics of blockchain technology. In other words, is the concept of “same user activities, same user risks, same rules” appropriate? Or does the underlying technology mean that similar user activities give rise to differing risks and a need for rules that are tailored to address those differences?

The regulatory framework for web3 activity in the United States is poorly developed, but the actions we analyzed show signs of its potential maturation and paint a picture that is not as dire as many industry pundits allege. Critically, none of the actions we analyzed provide conclusive evidence of regulators or courts “targeting developers” solely for developing, publishing, or deploying code. Instead, strong evidence suggests that regulators and courts have generally targeted businesses engaged in activities (that happen to include the use of code) in violation of regulations, consistent with RANP. This distinction is critically important: Targeting developers solely for publishing code would diminish web3’s potential and destroy the industry’s future in the U.S. Targeting business activity that facilitates violations of existing law (or the intent of existing law) creates a path for reasonable regulation of web3 that would still allow the underlying technology to thrive.

The focus on businesses instead of protocols is abundantly clear in the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) action against Coinbase as well as the judges analysis in the Uniswap matter. While the ambiguous and problematic language in the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) actions makes it more difficult to reach the same conclusion, an analysis of the totality of the CFTC’s actions and settlements in the web3 sector to date demonstrates that they have not yet targeted developers or protocols even though many opportunities exist to do so. Nevertheless, despite their targeting of businesses, both the CFTC and SEC actions received lower ratings because of their regulation-by-enforcement approach and their failure to foster innovation.

Otherwise, the actions of the SEC and CFTC are easy to distinguish. The SEC’s action against Coinbase’s wallet was an unpredictable extension of rules that is counterproductive – regulatory guidance and tailored rulemaking would do more to protect investors and foster financial innovation. Moreover, without clear regulations that govern the challenged conduct or that provide a path to compliance, the action stretches the scope of existing regulations to such an extent that it challenges notions of basic fairness and due process.

The CFTC, though, has demonstrated a more principled approach. The regulations that the CFTC uses clearly apply to the business activity challenged and their application was foreseeable. The actions, in our evaluation, do not violate notions of fairness and due process. But we strongly agree with Commissioner Mersinger’s dissent that argued that the preferable solution would have been to bring these businesses into a sandbox or a new regulatory structure that would foster innovation. The CFTC’s mandate to promote responsible innovation is being undermined by a lack of action to embrace novel derivatives structures that provide a concrete benefit to consumers over existing systems.

Based on our analysis of the actions against Coinbase (Wallet), Uniswap, ZeroEx, OPYN, and Deridex, we have assigned them the following grades, followed by a short analysis of each action’s outcome. You can also read the complete case studies here.

Grade: F

Status: Pending

The SEC brought charges against Coinbase, Inc. alleging that it operated as an unregistered broker under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 by enabling Coinbase wallet users to swap digital assets through a software protocol deployed to a blockchain. The complaint is generally consistent with RANP in that its focus is appropriately on Coinbase’s business activities relating to the wallet, not on the development of the wallet’s underlying code or the decentralized and autonomous protocol it uses to conduct swaps.

But while RANP argues that a strong case can be made to subject applications like the wallet’s swap feature to regulation, no existing U.S. regulation specifically prohibits such activity. While generally SEC guidance in this area underscores that whether an activity constitutes acting as a broker is often a facts and circumstances test, the examples in that guidance do not encompass the features of the wallet. In cases like this, RANP argues strongly against attempts to address “regulatory gaps” through unpredictable extensions of existing regulations, particularly where the activity and risks targeted are substantially different from the activity and risks existing regulations and guidance were intended to address. Unfortunately, that is precisely what the SEC has done in alleging that Coinbase offers brokerage services through its wallet.

As a result, the SEC’s complaint is another example of a regulatory action that is counterproductive when regulatory guidance and tailored rulemaking would do more to protect investors and foster financial innovation.

Read the full case study here.

Grade: A

Status: Motion to dismiss granted in judge’s final order and opinion

Judge Failla dismissed a class action brought against Uniswap Labs and other defendants that attempted to hold such defendants liable for the functioning of the Uniswap decentralized exchange protocol and the Uniswap.org website interface for the protocol. Judge Failla’s refusal to grant the plaintiffs relief is generally consistent with RANP. In particular, her legal reasoning provides strong support for excluding smart contract protocols and their developers from regulation and liability, yet justifies increasing the obligations of web3 applications as the risks they present to users increases.

Read the full case study here.

Grade: C

Status: Final Settlement of CFTC charges

The CFTC took action against ZeroEx, Inc. for its facilitation of trading of certain leveraged digital assets via the 0x smart contract protocol and the Matcha.xyz website interface in violation of the Commodities Exchange Act (CEA). While the CFTC’s use of ambiguous language and its reliance on regulation-by-enforcement has created unnecessary confusion about its intended overarching regulatory approach to web3, the CFTC’s action is generally consistent with RANP. The action provides strong evidence that the CFTC’s primary focus continues to be on businesses operating applications, not autonomous software protocols. This conclusion is supported by CFTC’s frequent reference to the Matcha interface as well as the settlement reached with ZeroEx, which enabled the Matcha Interface to continue to be accessible to U.S. persons following the delisting of the infringing assets from the interface. Meanwhile, the infringing assets remain accessible outside the U.S.

But the CFTC’s approach does fail to foster innovation in the manner called for in RANP. Not-for-profit applications like the Matcha Interface should be given flexibility under applicable regulations to promote innovation, particularly where leveraged assets can be offered safely and where they only represent a small subsection of the available assets, as was the case with the Matcha interface.

Nevertheless, the CFTC’s application of the CEA to the Matcha Interface essentially tracks RANP’s regulatory focus. It was a reasonable application of existing law, making it entirely foreseeable and avoidable, and it curtails potential regulatory arbitrage.

Read the full case study here.

Grade: B

Summary: Final Settlement of CFTC charges

The CFTC took action against Opyn, Inc. for its facilitation of the creation, purchase, sale, and trading of a blockchain-based derivative via a smart contract protocol, and the opyn.co website interface in violation of the CEA. As with its action against ZeroEx, the CFTC used ambiguous language and pursued regulation-by-enforcement. Even so, this action generally adheres to RANP and provides an even stronger signal that the CFTC is focused on regulating businesses, not software: The CFTC appears to be satisfied with Opyn’s application of stronger U.S. IP blocking following its settlement with the company. Meanwhile, its product remains accessible outside the U.S.

Still, the action represents a perplexing failure by the CFTC to support innovation. Opyn’s product offering is truly innovative, a perfect example of how programmable blockchains can remove many of the risks historically associated with derivatives and perpetual futures.

Nevertheless, the CFTC’s action tracks RANP’s regulatory focus. Opyn operated an interface that facilitated activity that was unlawful in the U.S., it failed to effectively block U.S. persons from using that interface, and it and its investors promoted its products on forums that were accessible to U.S. persons. Further, the CFTC’s action was a reasonable application of existing law and was entirely foreseeable.

Read the full case study here.

Grade: B+

Summary: Final Settlement of CFTC charges

The CFTC took action against Deridex, Inc. for its operation of a digital asset trading platform for leveraged digital assets and derivatives via a smart contract protocol and the app.deridex.org website interface in violation of the CEA. While the matter presents similar problems as the ZeroEx and Opyn actions regarding ambiguous language and regulation-by-enforcement, the CFTC’s action is generally consistent with RANP and essentially tracks its regulatory focus. Deridex operated an interface that facilitated activity that was unlawful in the U.S. and it allegedly blatantly disregarded U.S. laws in failing to make any attempt to block U.S. persons. As a result, the CFTC’s action was a reasonable application of existing law and was entirely foreseeable.

Read the full case study here.

***

The regulatory landscape across web3 is full of opportunity. Across the government, actors appear to be correctly focusing on the activities of businesses, not the activities of developers. This aligns with the central premise of RANP.

Beyond that, RANP argues that it is critical that the creation of new regulations or the application of existing regulations to web3 account for the differing benefits and risks of blockchain technology. The same user activities result in different risks and therefore demand different rules to yield the same regulatory outcome.

The CFTC appears to be the best positioned to capitalize on this next step.Their actions can be viewed as more in line with their legal mandate and regulations, but this is not to excuse the agency’s distinct lack of action to create policy frameworks around decentralized derivatives products. Promoting responsible innovation is a provision written into the CFTC’s mandate – one it has distinctly failed to meet here. The agency has the authority to review novel approaches to derivatives markets and make exemptions to existing rules that allow for innovation to be safely adopted. The use of such authority is critical to offer consumers a choice to engage with novel technology that presents distinct benefits while protecting against different risks.

***

Miles Jennings is General Counsel and Head of Decentralization of a16z crypto, where he advises the firm and its portfolio companies on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs and state and federal securities laws. You can follow him on X @milesjennings

Brian Quintenz is the Head of Policy for a16z crypto, where he helps to translate between the crypto and policy communities. You can follow him on X @brianquintenz

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.