Table of contents

- Case Study #1: SEC v. Coinbase

- Case Study #2: Risley v. Uniswap

- Case Study #3: CFTC v. ZeroEx

- Case Study #4: CFTC v. OPYN

- Case Study #5: CFTC v. Deridex

In this article, we provide the longer case studies for grading recent actions against Coinbase, Uniswap, ZeroEx, Opyn, and Deridex. If you’d like a more compact version, read this piece for background and our shorter evaluations.

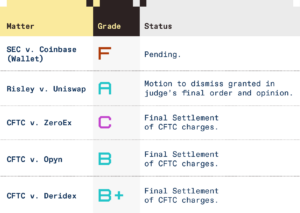

This chart also captures our grading.

Grade: F

Background

In July 2023, the SEC filed a complaint against Coinbase, Inc. (“Coinbase”) alleging a number of violations under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”), including that Coinbase provided broker services through the swap feature of its wallet (the “Wallet”).

The Wallet is a self-custodial wallet that is available for download and use on a wide array of personal computing devices, including Apple iPhones via the App Store. The primary purpose of the Wallet is to enable users to take custody and control of their digital assets. In addition to enabling users to store their digital assets, the Wallet includes a swap feature that enables users to trade thousands of digital assets onchain. To perform a swap, the user simply opens the feature in the Wallet, selects the blockchain they wish to trade on and inputs the two assets to be traded. The app then utilizes a smart contract protocol created by ZeroEx, Inc. (the “0x Protocol”) to check pricing on over 75 decentralized exchanges (“DEXes”). It then presents the user with the price of the transaction (including gas fees). The user can then select to execute the transaction by using the Wallet to send a message to the 0x Protocol, which routes the trade to the underlying DEX protocol providing the user with the best execution.

Within the context of RANP, the Wallet would properly be categorized as a “Web3 App” and the 0x Protocol, which functions as a DEX aggregator would be properly categorized as a “Protocol”.

It is important to note that while we have categorized the Wallet as a “Web3 App” for purposes of RANP, not all digital asset wallets should be similarly designated as such. As compared to websites that are hosted and operated by companies to enable users to access protocols, digital asset wallets are typically just software that is downloaded and run by users on their own devices. Given this, digital asset wallets are inherently more capable of being customized by users, and the developers of such software should not bear the responsibility for such customization. As a result, where a digital asset wallet is simply a generic tool that operates like a block explorer (a tool for reading and writing to blockchains), it would not be suitable for regulation as an application under RANP. However, where a digital asset wallet (1) abstracts away the complexity of a general tool and takes an active role in directing user behaviors (such as by providing users with a convenient method to swap assets) and (2) such functionality is maintained and updated by a person for business purposes, a strong argument can be made that the wallet should be classified as a “Web3 App” under RANP.

Protocol Characteristics

For purposes hereof, we will evaluate smart contracts that make up the 0x Protocol that enable the swap feature of the Wallet. Together, these smart contracts programmatically ensure that user swaps are routed to the underlying DEXes that provide the user with the best execution on their swap. As we previously wrote in part four of RANP, protocols deserving of regulatory exemptions should exhibit six key features.

| Characteristic | Applicable? | Discussion |

| Open Source | Unclear | The smart contracts and the offchain computational algorithm used by the protocol for routing trades via DEXs (the “Solver”) have all been made open source. |

| Decentralized | Yes | The 0x Protocol is not controlled by any person or concentrated group of related persons. Though the protocol makes use of offchain computational resources relating to the Solver, an open source version of the solver is available and can be run by anyone. This enables verification that all routing proposals proposed by the protocol are calculated in accordance with the open source Solver algorithm. |

| Autonomous | Partial | The 0x Protocol is partially autonomous (the offchain solver is operated by ZeroEx, Inc.). |

| Standardized | Yes | As evidenced by its compatibility with 75 DEXes, the 0x Protocol makes use of standards that maximize its composability. |

| Censorship Resistant | Yes | The 0x Protocol cannot be used to censor individuals or transactions (other than with respect to the Solver). |

| Permissionless | Yes | The 0x Protocol is permissionless and can be used by anyone to trade digital assets (other than with respect to the Solver). |

Based on the foregoing, the 0x Protocol used by the Wallet can be classified as a self-executing software protocol that functions as composable internet infrastructure. There is therefore a strong basis to shield it and its developers from regulation.

Application Characteristics

The Wallet is purpose built to enable the trading of digital assets (among other features) and does not currently take a fee on any swap transaction. The current swap feature of the application would be properly categorized as a not-for-profit app, purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets. As we explained in RANP, where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of policy objectives should favor fostering innovation. As a result, apps like the current Wallet should likely be exempt from registration requirements of any applicable regulation, but subject to compliance with upfront or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

However, according to the SEC’s allegations, the Wallet may have taken a fee on the principal of the trade at one point in time. In particular, in its complaint, the SEC alleged that “[d]uring the relevant period and through at least March 2023, Coinbase charged a flat fee of 1% of the principal amount of each transaction executed through the swap/trade feature in Wallet.” Assuming this allegation is true, the swap feature of the application would be properly categorized as an established for-profit app. As discussed in RANP, a stronger case can be made to apply regulation to established for-profit apps that directly facilitate trading of digital assets via DEXes.

Analysis

RANP argues that a strong case can be made to apply regulatory requirements to for-profit apps that facilitate trading of digital assets (as the Wallet was operated during the relevant period). However, no U.S. regulations specifically prohibit such functionality, including U.S. securities laws. Meanwhile, even though SEC guidance in this area underscores that whether an activity constitutes acting as a broker is often a facts and circumstances test, the examples in that guidance do not encompass the features of the wallet. Thus, while it may be appropriate for Congress to seek to address this “regulatory gap” through new legislation, RANP argues that it is not appropriate for regulators to unilaterally expand existing regulations to do so. Unfortunately, that is precisely what the SEC has done in alleging that Coinbase offers brokerage services through the Wallet.

Even if we assume that all of the SEC’s allegations that the digital assets available for swapping via the Wallet are being offered and sold in transactions that are subject to U.S. securities laws (a highly contested issue), the SEC’s complaint against Coinbase should fail. Coinbase’s activity (the development of the wallet and making it available to consumers) should not alone constitute broker services in violation of U.S. securities laws. As stipulated in Coinbase’s response to the SEC’s complaint, the SEC’s complaint is “…devoid of allegations to establish that Coinbase performs any such relevant ‘broker’ activities through Wallet. The SEC offers no well-pleaded facts that Coinbase uses Wallet to take or process orders; or to negotiate transactions for customers; or to make investment recommendations, provide digital asset valuations, or offer other transactional advice to customers; or to recommend or arrange customer financing; or to process trade documentation; or to hold customer assets or funds.”

In fact, Coinbase’s wallet’s functionality does not implicate nearly any of the sixteen different factors that have commonly been used by the SEC in categorizing activity as broker activity:

| Participating in discussions between a company and potential investors or negotiating the terms of a securities transaction on behalf of buyers and/or sellers | Not applicable |

| Assisting in structuring transactions | Not applicable |

| Receiving transaction-based compensation (i.e., a commission or some form of compensation that is tied to the size or success of a securities offering or transaction) | Applicable, but see below. |

| Engaging in “pre-screening” potential investors to determine their eligibility to purchase securities | Not applicable |

| Engaging in “pre-selling” the issuance of securities to gauge the level of interest of potential investors | Not applicable |

| Conducting or assisting with the sale of securities | Not applicable – Software run on a user’s device that is trustless does not give rise to the conflicts of interest this activity normally gives rise to |

| Providing advice regarding the value of securities | Not applicable |

| Locating issuers of securities on behalf of investors | Not applicable |

| Handling customer funds and securities | Not applicable |

| Soliciting securities transactions | Not applicable – See below. |

| Disseminating quotes for securities or other pricing information | Not applicable – The application does not disseminate quotes, it merely enables the user to read the blockchain upon request. |

| Actively (rather than passively) finding investors | Not applicable |

| Sending private placement memoranda, subscription documents, and due diligence materials to potential investors;Venable LLP Finders and Unregistered Broker-Dealers | Not applicable |

| Advising on portfolio allocations to accommodate an investment | Not applicable |

| Providing analyses of potential investments | Not applicable |

| Providing potential investors with confidential information identifying other investors and their capital commitments | Not applicable |

Transaction-based compensation is often referred to by the SEC as the hallmark of broker activity. However, the SEC’s own stated policy rationale for broker registration requirements of the Exchange Act fails to justify its action against Coinbase’s Wallet. In particular, the SEC’s policy rationale is often referred to the “salesmen’s stake” conflict of interest, but such conflict does not exist here. While Coinbase allegedly received a fee during the relevant period, which would technically constitute transaction-based compensation”, the salesmen’s stake conflict does not arise where there is no solicitation for investment or recommendation for purchases or sales. Yes, Coinbase makes more money if people engage in more transactions, but without a specific solicitation for transactions, the conflict of interest is no different than that of any counterparty or service provider in any sort of business arrangement. Ordinary business arrangements do not trigger broker registration obligations under the Exchange Act, yet the SEC is alleging that they do here.

So, the relevant question becomes whether Coinbase actively solicited investors to trade certain digital assets. While the SEC alleged that Coinbase solicits customers to trade via its wallet by stating on its public blog that “Coinbase Wallet brings the expansive world of DEX trading to your fingertips, where you can easily swap thousands of tokens, trade on your preferred network, and discover the lowest fees,” these statements are not evidence that Coinbase actively solicits investors. As discussed in Case Study #3 below, a judge in a recent class action involving Uniswap Labs rejected plaintiffs’ claims that statements made by Uniswap Labs similar to Coinbase’s statements constituted a solicitation to purchase digital assets. There, Judge Failla ruled that the defendants offered “nothing more than a conclusory allegation that Defendants” solicited digital asset purchases by the Defendants. The SEC’s complaint’s allegation of solicitation fails for the same reasons. Per Judge Failla’s ruling, “[a]fter all, no plaintiff would sue the New York Stock Exchange or NASDAQ for tweeting that its exchange was a safe place to trade after that plaintiff had lost money due to an issuer’s fraudulent schemes.”

Furthermore, the extension of broker rules under U.S. securities laws to the activity engaged in by Coinbase in relation to the Wallet is both unnecessary and counterproductive. Such rules are largely meant to protect investors in securities from conflicts of interest relating to the assets traded and the manner of execution, risks that are not present with the Wallet (regardless of whether or not the offers and sales of digital assets in secondary markets are subject to securities laws). Not only is the swap feature of the Wallet not opinionated about which assets users trade (it does not curate the list of tradable assets and it does not prioritize assets in a manner that might trigger concerns about conflicts of interest), but because the smart contracts of the 0x Protocol are simply computer code that can be analyzed by anyone, the 0x Protocol can provide an auditable trail for the best execution on all trades initiated via the Wallet’s swap feature – thereby already accomplishing what existing broker rules can only hope to achieve with regard to Best Execution requirements. The SEC’s action against Coinbase’s Wallet therefore runs counter to its own core mission of protecting investors.

It is also not uncommon for the SEC to find activity that is similar to the Wallet’s functionality to be outside the bounds of broker regulations. Through a number of “No Action Letters”, the SEC has deemed “Finders”, “Internet Portals” and “Online Bulletin Boards”, platforms with similar functionality to the Wallet, to not be brokers even though they facilitated offers and sales of securities. One of the key disqualifying factors from these safe harbors is the presence of transaction-based compensation, the presence of which gives rise to potential conflicts of interest because the platforms are all operated and controlled by their creators. However, as described above, because of the way the Wallet is architected, transaction-based compensation on trades initiated through the Wallet does not give rise to conflicts of interest. As a result, the Wallet’s swap feature should not be deemed to be broker activity and, rather than bringing this action, the SEC should have provided guidance or “no action” relief to applications like Coinbase’s wallet and other DEX interfaces.

In conclusion, while there are risks inherent to the operation of for-profit apps that facilitate trading of digital assets (as the Wallet was allegedly operated during the relevant period), those risks are distinctly different that the risks broker rules and guidance are meant to address. Logic and RANP therefore necessitate that new regulations be developed to address such new risks – existing regulations must not be unpredictably extended via regulation-by-enforcement, as such actions will unnecessarily curtail a burgeoning technology.

Given the foregoing, we assign a grade of “F” to this regulatory action.

Grade: A

Background

In August 2023, the judge presiding over a class action lawsuit brought against Universal Navigation, Inc. (“Uniswap Labs”) and certain other defendants (including Andreessen Horowitz) in connection with the operation and functioning of the Uniswap decentralized exchange protocol (the “Uniswap Protocol”) and the Uniswap.org website interface for the protocol (the “Uniswap Interface”), dismissed the plaintiffs’ complaint in full.

In the matter, the plaintiffs brought two primary claims under U.S. securities laws, one for rescission of certain contracts under Section 29(b) of the Exchange Act and one for defendants’ alleged violation of Section 12(a)(1) of the Securities Act of 1933 (the “Securities Act”). Each of these claims related to plaintiffs trading of certain digital assets alleged to be securities by the plaintiffs, and the defendants related activity with respect to the Uniswap Protocol and Uniswap Interface, which the plaintiffs alleged should have been regulated as an “exchange” or “broker or dealer” under U.S. securities laws.

The Uniswap Protocol is a decentralized exchange smart contract protocol that enables anyone who accesses it to swap digital assets. In addition, Uniswap Labs – a team that functions independently of the protocol – operates the Uniswap Interface, which facilitates a user-friendly means of accessing the Uniswap Protocol. The Uniswap Interface is one of dozens of frontend interfaces designed to access the Uniswap Protocol that are operated by independent parties. To perform a swap, a user navigates to the Uniswap Interface (or any other frontend), connects a wallet and then inputs the two assets to be traded. The app then checks pricing on versions 2 and 3 of the Uniswap Protocol, before presenting the user with the proposed execution and price of the transaction (including gas fees). The user can then select to execute the transaction using the Uniswap Interface to prompt their connected wallet to send a message to the Uniswap Protocol, which then self-executes the trade.

Within the context of RANP, the Uniswap Interface would properly be categorized as a “Web3 App” and the Uniswap Protocol, which functions as a DEX, would properly be categorized as a “Protocol”.

Protocol Characteristics

Together, smart contracts of the Uniswap Protocol enable users to swap digital assets. While the plaintiffs in this matter alleged that the defendants controlled and operated the Uniswap Protocol, such allegations were entirely and demonstrably false.

| Characteristic | Applicable? | Discussion |

| Open Source | Yes | The smart contracts for both v2 and v3 of the Uniswap Protocol are available for use pursuant to standard open source licenses. |

| Decentralized | Yes | The Uniswap Protocol is not controlled by any person or concentrated group of related persons. |

| Autonomous | Yes | The Uniswap Protocol is fully autonomous. |

| Standardized | Yes | The Uniswap Protocol makes use of standards that maximize its composability, including ERC-20. |

| Censorship Resistant | Yes | The Uniswap Protocol cannot be used to censor individuals or transactions. |

| Permissionless | Yes | The Uniswap Protocol is permissionless and can be used by anyone to deploy liquidity pools and to trade digital assets. |

Based on the foregoing, the Uniswap Protocol can be classified as a self-executing software protocol that functions as composable internet infrastructure. There is therefore a strong basis to shield it and its developers from regulation and liability.

Application Characteristics

The Uniswap Interface is purpose-built to enable access to the Uniswap Protocol for the purpose of trading digital assets. The application does not currently take a fee on any swap transaction (though fees do accrue to independent participants that provide liquidity with respect to digital asset pairs to the protocol’s smart contract pools, thereby providing liquidity for trades routed through the protocol). The Uniswap Interface would therefore currently be properly categorized under RANP as a not-for-profit app, purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets. As we explained in RANP, where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of policy objectives should favor fostering innovation. As a result, apps like the Uniswap Interface should likely be exempt from registration requirements of any applicable regulation, but subject to compliance with upfront or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

Analysis

The plaintiff’s Section 29(b) claim under the Exchange Act sought to rescind the trades initiated by the plaintiffs via the protocol and interface. To win on such a claim, the plaintiffs were required to show that (i) the contracts underpinning such trades were prohibited transactions, (ii) that the plaintiffs were in contractual privity with the defendants and (iii) that the plaintiffs were the types of people the Exchange Act was designed to protect. These requirements reflect the common-law principle that a contract to perform an illegal act is void.

In determining that the defendants had no liability under Section 29(b) of the Exchange Act, Judge Failla wrote that “it defies logic that a drafter of computer code underlying a particular software platform could be liable under Section 29(b) for a third-party’s misuse of that platform.” Elaborating on this point, Judge Failla recognized that the core smart contracts deployed by Uniswap Labs had an entirely legal purpose and remain constant, but that users of the Uniswap Protocol had deployed the underlying smart contracts for the pools of digital assets that the plaintiffs took issue with. When combined with the decentralized, autonomous and permissionless nature of the Uniswap Protocol, Judge Failla concluded that these factors demanded that the Uniswap Protocol itself, as well as the defendants, could not be liable under Section 29(b) as currently constituted.

The plaintiff’s Section 12(a)(1) claim under the Securities Act sought to hold the defendants liable as statutory sellers under two separate theories, both of which were rejected by Judge Failla.

Judge Failla’s rulings and the legal reasoning behind them are worth exploring within the context of RANP.

First, because plaintiffs’ claims against defendants failed as a result of the defendants not having created or deployed the “pair” smart contracts that were directly involved in illegal trading of digital assets, Judge Failla did not need to address how liability could have arisen. For instance, if one of the defendants had deployed the offending “pair” smart contracts, it is unclear whether Judge Failla would have found that a person liable for the activity facilitated by such smart contracts if such person did not also facilitate the activity via an application. But in light of Judge Failla’s recognition of the distinction between a protocol and an interface, there is good reason to believe that she may have been hesitant to apply liability if no interface were available.

To emphasize this point, it is worth reviewing Judge Failla’s use of a self-driving car analogy in her ruling, “[i]n this regard, the Court sees merit in Defendants’ counterpoint that this case is more like an effort to hold a developer of self-driving cars liable for a third party’s use of the car to commit a traffic violation or to rob a bank. In those circumstances, one would not sue the car company for facilitating the wrongdoing; they would sue the individual who committed the wrong.” It remains an open question whether, to modify the analogy, a court would find liability even if a self-driving car were specifically designed to commit a traffic violation, if the manufacturer never facilitated access or use of such car. As a result, courts that properly distinguish applications from protocols should not find a party liable without showing that they facilitate access to or use of something unlawful. This approach would generally be consistent with RANP, which argues that where the primary purpose of a protocol and the application referencing it is to facilitate illegal transactions, the argument for applying regulation (and consequently, liability), is highest. But that argument falters without the presence of the application that facilitates access to the protocol.

Second, Judge Failla’s reasoning can be extrapolated to suggest that had the defendants profited from trading activity via the Uniswap Interface and Uniswap Protocol, the plaintiffs may have been better positioned to pursue a Section 12 solicitation claim. Such an outcome is also generally consistent with RANP, which argues that there is a stronger basis for applying regulation (and consequently, liability) to established for-profit apps that directly facilitate trading of digital assets via DEXs. However, even if plaintiffs’ allegations that the defendants stood to profit from the challenged transactions were not “entirely conclusory and devoid of factual support,” the outcome should have remained the same because the defendants did not urge plaintiffs to purchase the digital at issue and the plaintiffs did not purchase the tokens because of any such solicitation by defendant. Ultimately, they simply used a tool (the Uniswap Interface and Uniswap Protocol) that is not opinionated about what digital assets a user swaps and that does not promote the acquisition or sale of any individual asset or activity.

Third, even though Judge Failla was not required to opine on whether the Uniswap Interface or Uniswap Protocol functioned as an “exchange” or that defendants acted as “brokers” under the Exchange Act, her reasoning with respect to the actions of the defendants and the characteristics of the Uniswap Protocol provide a strong indication that she would also have rejected these allegations as insufficient. Further, such allegations may have been even more difficult to prove in this case than in the SEC v. Coinbase case regarding Coinbase’s Wallet discussed in Case Study #1 above, because in this case the Uniswap Interface never collected any fees.

As a result, Judge Failla’s ruling reinforces the approach set forth in RANP and her statements are a strong indicator that neither regulators nor courts should be stretching existing regulations beyond their intended purpose, stating here that “…Plaintiffs’ claims are better addressed to Congress than to this Court.”

Given the foregoing, we assign a grade of “A” to this legal action.

Grade: C

Background

In September 2023, the CFTC issued an order and entered into a settlement with ZeroEx, Inc. (“ZeroEx”), the creator of a smart contract protocol that facilitates the trading of digital assets by aggregating trading opportunities across DEXes (the “0x Protocol”), and the Matcha.xyz website interface (the “Matcha Interface”), both of which were accessible to persons in the U.S. The CFTC alleged that the Matcha Interface listed multiple digital assets that provided traders with approximately 2:1 leveraged exposure to digital assets such as ether and bitcoin, and found that these assets were leveraged or margined retail commodity transactions, which could only be offered on a registered exchange in accordance with the CEA.

In settlement of the order, ZeroEx was required to pay a fine of $200,000 and cease and desist from violating the CEA. Following the settlement, the Matcha Interface has delisted the relevant assets and continues to be accessible to U.S. persons.

Within the context of RANP, the Matcha Interface would properly be categorized as a “Web3 App” and the 0x Protocol, which functions as a DEX, would be properly categorized as a “Protocol”.

Protocol Characteristics

For purposes hereof, we will evaluate the characteristics of the DEX aggregator smart contracts that make up the 0x Protocol. Together, these smart contracts programmatically ensure that user swaps are routed to the underlying DEXes that provide the user with the best execution on their swap.

| Characteristic | Applicable? | Discussion |

| Open Source | Unclear | The smart contracts and the offchain computational algorithm used by the protocol for routing trades via DEXs (the “Solver”) have all been made open source. |

| Decentralized | Yes | The 0x Protocol is not controlled by any person or concentrated group of related persons. Though the protocol makes use of offchain computational resources relating to the Solver, an open source version of the solver is available and can be run by anyone. This enables verification that all routing proposals proposed by the protocol are calculated in accordance with the open source Solver algorithm. |

| Autonomous | Partial | The 0x Protocol is partially autonomous (the offchain solver is operated by ZeroEx, Inc.). |

| Standardized | Yes | As evidenced by its compatibility with 75 DEXes, the 0x Protocol makes use of standards that maximize its composability. |

| Censorship Resistant | Yes | The 0x Protocol cannot be used to censor individuals or transactions (other than with respect to the Solver). |

| Permissionless | Yes | The 0x Protocol is permissionless and can be used by anyone to trade digital assets (other than with respect to the Solver). |

Based on the foregoing, the 0x Protocol can be classified as a self-executing software protocol that functions as composable internet infrastructure. There is therefore a strong basis to shield it and its developers from regulation.

Application Characteristics

The Matcha Interface is an application that is purpose built to enable the trading of digital assets and does not take a fee on any swap transaction. As a result, under RANP the application would be properly categorized as a not-for-profit app, purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets. It was not purpose-built to facilitate trading of leveraged digital assets or other derivatives. As we explained in RANP, where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of policy objectives should favor fostering innovation. Such apps should likely be exempt from registration requirements of any applicable regulation, but subject to compliance with upfront or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

Analysis

The CFTC order sets forth that ZeroEx’s enablement of trading of certain leveraged digital assets violated Section 4(a) of the Commodities Exchange Act. Section 4(a) prohibits persons from “conducting an office or business in the United States for the purpose of soliciting or accepting orders for, or otherwise dealing in, off-exchange leveraged or margined retail commodity transactions with customers who were not eligible contract participants or eligible commercial entities.” The order precedes any formal rulemaking or guidance to the industry, and it uses imprecise language, failing to delineate whether the development and deployment of the 0x Protocol or the operation of the Matcha Interface were the primary reason for the CFTC bringing its action.

Under RANP, this result creates two issues:

In her dissent, Commissioner Mersinger highlighted these issues and argued that the CFTC’s regulation-by-enforcement approach was unnecessary, stating that “the Commission’s Orders in these cases give no indication that customer funds have been misappropriated or that any market participants have been victimized by the DeFi protocols on which the Commission has unleashed its enforcement powers.”

While Commissioner Mersinger is correct in her critiques of the CFTC’s actions, these shortcomings should not be overstated.

With respect to the first issue, while the CFTC’s language creates confusion, it does not support a conclusion that the CFTC intends to target developers or protocols. Throughout the CFTC’s order, the Matcha Interface is referenced frequently (e.g., “By accessing Matcha’s website, users could trade on a peer-to-peer basis in thousands of different digital asset trading pairs for settlement on various blockchains.”) and the CFTC noted that ZeroEx “…took no steps to restrict users who were not eligible contract participants.” Further, the CFTC justifies its treatment of ZeroEx as an “offeror” subject to Section 4(a) of the CEA because it “…deploy[ed] a decentralized protocol (the 0x protocol) and operat[ed] a front-end user interface (Matcha)…” (emphasis added).

The wording of the order, especially in the context of the other actions the CFTC has brought, suggests that the operation of the Matcha Interface and the failure to block U.S. persons from accessing it was the key factor that led to the action. This perspective is supported by the settlement between the CFTC and ZeroEx, which enabled the Matcha Interface to continue to be accessible to U.S. persons following the delisting of the infringing assets from the interface. Meanwhile, the infringing assets remain accessible outside the United States.

As a result, while the CFTC’s pursuit of regulation-by-enforcement is sub-optimal, creates confusion, and is inefficient, it does not mean the CFTC is targeting developers of software protocols, as opposed to the operators of interfaces or other services that interact with U.S. persons. In fact, all of the CFTC’s actions in the sector to date have similarly focused on business activity. We are not aware of any examples where the CFTC has taken an action that exclusively focused on the development and deployment of software protocols, without any accompanying ongoing business operations, most often in relation to the ongoing operation of an interface.

With respect to the second issue, we agree with Commissioner Mersinger’s dissent, which argued that the preferable solution would have been to bring ZeroEx into a sandbox or a new regulatory structure that would foster innovation. Coinbase International Exchange, for instance, just received regulatory approval by the Bermuda Monetary Authority to offer perpetual crypto futures contracts, a strong example of promoting innovation and customer protection through updating existing regulations.

However, the CFTC’s order against ZeroEx is not an example of a regulator stretching existing regulations beyond their well-understood meaning. The CEA grants the CFTC very broad authority, and its application here was foreseeable and in line with the intent of the regulation – the offending assets clearly involved leverage and therefore provided users with synthetic exposure to the underlying asset. Most importantly, a path to compliance still exists – here, the CFTC appears to be satisfied with ZeroEx only removing the offending assets from the Matcha Interface, and such assets were only a small percentage of the platform’s activity. As a result, the CFTC’s action can be easily distinguished from the SEC’s action against Coinbase discussed in Case Study #1.

Further, in the absence of a regulatory sandbox or a new regulatory structure that would foster innovation, it is unsurprising that the CFTC brought this action against ZeroEx Its failure to apply the CEA to businesses utilizing smart contracts (as opposed to proprietary software) would be prejudicial to centralized businesses and would encourage regulatory arbitrage through the use of smart contracts. While the goal of fostering innovation is a noble one, the rules facilitating that goal need to be transparent and available to all.

As a result, while the CFTC should be admonished for its ambiguous language, which will continue to create uncertainty rather that clarity, and a regulation-by-enforcement approach that fails to update its rulebook to foster innovation in the leveraged digital asset and digital asset derivatives spaces, this action does not run in opposition of RANP or notions of fairness.

Given the foregoing, we assign a grade of “C” to this legal action.

Grade: B

Background

In September 2023, the CFTC issued an order and entered into a settlement with Opyn, Inc. (“Opyn”), the creator of a smart contract protocol (the “Opyn Protocol”) and the opyn.co website interface (the “Opyn Interface”) that facilitated the creation, purchase, sale, and trading of a blockchain-based derivative called oSQTH (more commonly known as “Squeeth”), allegedly in violation of the CEA. During the relevant period, Squeeth was accessible to persons in the U.S. via the Opyn Interface (as well as other methods like through an unnamed decentralized exchange or by accessing the Opyn Protocol directly via a block explorer). Opyn sought to block U.S. users from using the Opyn Interface to access the Opyn Protocol by applying an internet protocol (“IP”) address blocker to the interface. However, the CFTC alleged that such steps were not sufficient to block U.S. users.

In settlement of the order, Opyn was required to pay a fine of $250,000 and cease and desist from violating the CEA. Following the settlement, the Opyn Interface is no longer accessible to U.S. persons.

Within the context of RANP, the Opyn Interface would properly be categorized as a “Web3 App” and the Opyn Protocol would be properly categorized as a “Protocol”.

Protocol Characteristics

For purposes hereof, we will evaluate the characteristics of the smart contracts that make up the Opyn Protocol.

| Characteristic | Applicable? | Discussion |

| Open Source | Yes | The smart contracts for the Opyn Protocol are available for use pursuant to standard open source licenses. |

| Decentralized | Uncertain | The Opyn Protocol is not controlled by any person or concentrated group of related persons, however, the CFTC alleged that Opyn “retained a degree of control over the Opyn Protocol by retaining the ability to impose transaction fees on the minting of oSQTH, as well as the ability to effect a shutdown of the protocol…” |

| Autonomous | Yes | The Opyn Protocol is fully autonomous. |

| Standardized | Yes | The Opyn Protocol makes use of standards that maximize its composability. |

| Censorship Resistant | Yes | The Opyn Protocol cannot be used to censor individuals or transactions. |

| Permissionless | Yes | The Opyn Protocol is permissionless and can be used by anyone. |

Based on the foregoing, the Opyn Protocol had characteristics that make it function similarly to composable internet infrastructure. However, the protocol was alleged to be less decentralized than the protocols discussed in Case Studies #1 through #3, though the order does not articulate how that factored into the CFTC’s decision making.

Application Characteristics

The Opyn Interface is an application that is purpose built to enable the creation, purchase, sale and trading of a blockchain-based derivative called Squeeth and does not take a fee on any transactions. As detailed in the CFTC’s order, Squeeth’s classification as a derivative meant that is not permitted to be offered or sold in the U.S., other than through a registered platform, which the Opyn Interface was not. As a result, under RANP the Opyn Interface would be properly categorized as a not-for-profit app, purpose-built to directly facilitate activity that is unlawful in the U.S. As we explained in RANP, where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of the policy objectives of any applicable regulations should favor fostering innovation. However, such policy objectives must be weighed against the policy objectives behind the regulations that an application runs afoul of, and where an application is purpose built to facilitate activity that violates such regulations, it may be unreasonable to permit such activity to continue. The goal of fostering innovation does not and should not justify lawlessness.

Analysis

The CFTC order sets forth that Opyn’s activity constituted multiple violations of the CEA, including:

With respect to the violation of Section 4(a) and Section 5h(a)(1) of the CEA, the CFTC’s order specifically referenced Opyn’s use of the Opyn Protocol and Opyn Interface and noted that “Opyn conducted an office or business in the United States…” However, the order does not specify whether it was Opyn’s development of the Opyn Protocol or its operation of the Opyn Interface that gave rise to the violations.

With respect to the violation of Section 4d(a)(1), the CFTC’s order emphasized that Opyn acted as an unregistered FCM by “…soliciting and accepting orders for swaps via the Opyn Protocol.” Such solicitations and acceptances directly relate to the business activities of Opyn carried out through the Opyn Interface as well as its online marketing efforts. While the order also referenced Opyn’s development and deployment of the Opyn Protocol (“…by creating and deploying smart contracts that were designed and intended to allow users of the Opyn Protocol to contribute collateral and establish perpetual contract positions, Opyn accepted property to margin these transactions.”), such position would have likely been challenged had the matter been brought before a court. There, Opyn could have argued that the decentralized nature of the Opyn Protocol meant that Opyn could not have played any role in the acceptance of property to margin the relevant transactions – such acceptance happens autonomously and without any influence of the original developer of the smart contracts. However, even if this argument had been successful, Opyn’s defense may still not have prevailed given its ongoing operation of the Opyn Interface.

The lack of precise language with respect to the Section 4(a) and Section 5h(a)(1) claims and the reference to the Opyn Protocol in the Section 4d(a)(1) claim are problematic and introduce uncertainty about the CFTC’s regulatory focus and intentions. Further, the lack of any discussion of the characteristics of the Opyn Protocol, including Opyn’s ability to shutdown the protocol, makes it difficult for onlookers to ascertain which facts were most important in driving the outcome of the order.

However, before concluding that the CFTC is targeting developers merely for developing code, it is helpful to provide some additional context about Opyn’s business activities.

First, for several years law firms have regularly advised companies in the crypto sector to go further than simply blocking IP addresses. In order to effectively block U.S. persons, established best practices include three components: (1) blocking U.S. IP addresses; (2) blocking IP addresses associated with well-known VPNs; and (3) blocking any wallet address from using the protocol if that address has been associated with an address covered by (1) or (2). Here, it appears that Opyn only blocked U.S. addresses.

Second, industry observers in the U.S. who have never used the Opyn Protocol are nevertheless likely to be quite familiar with its product, Squeeth. That is because the asset was heavily marketed and discussed on forums accessible to U.S. persons, including Twitter and Medium. These promotional efforts were undertaken by a number of persons unrelated to Opyn, but they were also undertaken by Opyn itself as well as its investors, often with direct links to the Opyn Interface and without notices that Squeeth was not available for purchase in the U.S.

Given the foregoing, it should not come as any surprise that the CFTC took action here. In August 2021, the CFTC brought a similar action against BitMex, a cryptocurrency derivatives trading platform, alleging that BitMEX’s IP blocking was insufficient, that it heavily marketed to U.S. customers, and that it had knowledge that a substantial portion of its trading volume was coming from U.S. persons. In that matter, BitMEX faced a fine of $100M.

In light of the foregoing, it was entirely foreseeable that the CFTC would bring an action against Opyn under the CEA as such action is in line with the intent of the regulation – Squeeth was clearly a derivative. Had the matter gone to court, we do not believe the CFTC’s charges with respect to Section 4d(a)(1) would have succeeded based solely on Opyn’s development of the Opyn Protocol (as discussed above), and it remains to be seen whether the CFTC would have ultimately prevailed on such charge given Opyn’s ongoing operation of the Opyn Interface, its failure to effectively block U.S. persons and it and its investors’ promotions targeting U.S. persons.

As a result, the CFTC should again be admonished for its regulation-by-enforcement approach and its use of deliberately ambiguous language that attempts to mask its intent and broaden its potential reach. These maneuvers will only continue to create uncertainty rather than clarity. Further, Opyn’s Squeeth is a truly innovative product and is a perfect example of how blockchain-based products can remove many of the risks historically associated with derivatives and perpetual futures, yet existing regulations do not permit it to be offered and sold in the U.S. We therefore would have strongly preferred the CFTC to have enabled Squeeth to exist in a regulatory sandbox or a new regulatory structure that would promote such innovations.

However, despite these objections, one cannot say that this action defies notions of fairness. So long as the CFTC is satisfied with Opyn Inc.’s application of stronger U.S. IP blocking post-settlement and is not demanding the shutdown of the Opyn Protocol, the action would also not be in conflict with RANP.

Given the foregoing, we assign a grade of “B” to this legal action.

Grade: B+

Background

In September 2023, the CFTC issued an order and entered into a settlement with Deridex, Inc. (“Deridex”), the creator of a smart contract protocol (the “Deridex Protocol”) and the app.deridex.org website interface (the “Deridex Interface”) that functioned as a digital asset trading platform and offered leveraged trading of digital asset derivatives, allegedly in violation of the CEA. During the relevant period, the platform was accessible to persons in the U.S. either via the Deridex Interface or by accessing the Deridex Protocol directly via a block explorer. The CFTC alleged that Deridex did not take any steps to block U.S. persons.

In settlement of the order, Deridex was required to pay a fine of $100,000 and cease and desist from violating the CEA. Following the settlement, the Deridex Interface does not appear to be in operation and is no longer accessible.

Within the context of RANP, the Deridex Interface would properly be categorized as a “Web3 App” and the Deridex Protocol would be properly categorized as a “Protocol”.

Protocol Characteristics

For purposes hereof, we will evaluate the characteristics of the smart contracts that make up the Deridex Protocol.

| Characteristic | Applicable? | Discussion |

| Open Source | Yes | The smart contracts for the Deridex Protocol are available for use pursuant to standard open source licenses. |

| Decentralized | Uncertain | The CFTC alleged that Deridex retained substantial control over the Deridex Protocol, noting that Deridex “retained the ability to update relevant smart contract code to adjust how the smart contracts operated in order to, among other things, suspend trading or prevent users from depositing collateral.” |

| Autonomous | Yes | The Deridex Protocol was partially autonomous, as it remained under the control of Deridex |

| Standardized | Yes | The Deridex Protocol made use of standards that maximize its composability. |

| Censorship Resistant | Uncertain | Given Deridex’s alleged control of the Deridex Protocol, Deridex would likely have been positioned to censor individuals or transactions. |

| Permissionless | Yes | The Deridex Protocol was permissionless and could be used by anyone. |

Based on the foregoing, the Deridex Protocol had characteristics that make it function similarly to composable internet infrastructure. However, the protocol was alleged to be less decentralized than the protocols discussed in Case Studies #1 through #3, though the order does not articulate how that factored into the CFTC’s decision making. It is worth noting though that the CFTC alleged that Deridex held custody of user assets that were deployed to the protocol, something that could not be true if the protocol were truly decentralized.

Application Characteristics

The Deridex Interface is an application that is purpose built to enable leveraged trading of digital asset derivatives and Deridex collected aggregate fees on transactions that were de minimis. As detailed in the CFTC’s order, leveraged trading of derivatives is not permitted to be offered in the U.S., other than through a registered platform, which the Deridex Interface was not. As a result, under RANP the Deridex Interface would be properly categorized as a not-for-profit app, purpose-built to directly facilitate activity that is unlawful in the U.S. As we explained in RANP, where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of the policy objectives of any applicable regulations should favor fostering innovation. However, such policy objectives must be weighed against the policy objectives behind the regulations that an application runs afoul of, and where an application is purpose built to facilitate activity that violates such regulations, it may be unreasonable to permit such activity to continue. The goal of fostering innovation does not and should not justify lawlessness.

Analysis

The CFTC order sets forth that Deridex’s activity constituted multiple violations of the CEA, including:

With respect to the violation of Section 4(a) and Section 5h(a)(1) of the CEA, the CFTC’s order specifically referenced Deridex’s use of the Deridex Protocol and Deridex Interface and noted that “Deridex conducted an office or business in the United States…” However, the order does not specify whether it was Deridex’s development of or control over the Deridex Protocol or its operation of the Deridex Interface that gave rise to the violations.

With respect to the violation of Section 4d(a)(1), the CFTC’s order emphasizes that Deridex acted as an unregistered FCM by “…soliciting and accepting orders for swaps via the Deridex Protocol.” Such solicitations and acceptances directly relate to the business activities of Deridex carried out through the Deridex Interface as well as its online marketing efforts. While the order also references Deridex’s development and deployment of the Deridex Protocol (“…by creating and deploying smart contracts that were designed and intended to allow users of the Deridex Protocol to contribute collateral and establish perpetual contract positions, Deridex accepted property to margin these transactions.”), such position would have likely been challenged had the matter been brought before a court. There, Deridex could have argued that the decentralized nature of the Deridex Protocol meant that Deridex could not have played any role in the acceptance of property to margin the relevant transactions – such acceptance happens autonomously and without any influence of the original developer of the smart contracts. However, this argument was unlikely to have been successful given that the Deridex Protocol was allegedly not decentralized. Further, even if the argument had been successful, Deridex’s defense may still not have prevailed given its ongoing operation of the Deridex Interface.

The lack of precise language with respect to the Section 4(a) and Section 5h(a)(1) claims and the reference to the Deridex Protocol in the Section 4d(a)(1) claim are problematic and introduce uncertainty about the CFTC’s regulatory focus and intentions. Further, the lack of any discussion of the characteristics of the Deridex Protocol, including Deridex Inc’’s level of control over the protocol and its custodying of assets, makes it difficult for onlookers to ascertain which facts were most important in driving the outcome of the order.

The foregoing violations are nearly identical to the violations alleged in the CFTC’s order against Opyn, as discussed in Case Study #4. As a result, the same context provided in that action regarding IP blocking, BitMEX and other protocols are useful here, where Deridex allegedly did not even attempt to block U.S. persons. Thus, even though it is less clear what promotional efforts Deridex engaged in as compared to Opyn, Deridex’s allegedly blatant disregard of U.S. law and the alleged lack of decentralization likely justified the CFTC’s move against it.

As a result, as in the Opyn case, the CFTC should again be admonished for its regulation-by-enforcement approach and its use of vague and sometimes deliberately ambiguous language. However, despite these objections, one cannot say that this action defies notions of fairness.

Given the foregoing, we assign a grade of “B+” to this legal action.

***

Miles Jennings is General Counsel and Head of Decentralization of a16z crypto, where he advises the firm and its portfolio companies on decentralization, DAOs, governance, NFTs and state and federal securities laws. You can follow him on X @milesjennings

Brian Quintenz is the Head of Policy for a16z crypto, where he helps to translate between the crypto and policy communities. You can follow him on X @brianquintenz

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.