No matches

We couldn't find any matches for "".

Double check your spelling or try a different search term.

Still can't find what you're looking for? Check out our featured articles.

Featured Articles

AI needs crypto — especially now

Tourists in the bazaar: Why agents will need B2B payments — and why stablecoins will get there first

Every company faces some version of the “cold start problem”: How do you get started from nothing? How do you acquire customers? How do you create network effects — where your product or service becomes more valuable to its users as more people use it — that create incentives for even more customers to sign up?

In short, how do you “go to market” and convince potential customers to spend their money, time, and attention on your product or service?

The response by most organizations in web2 — the Internet era defined by large centralized products/services like Amazon, eBay, Facebook, and Twitter, in which the vast majority of value accrues to the platform itself rather than to the users — is to invest significantly in sales and marketing teams as part of a traditional go-to-market (GTM) strategy that focuses on generating leads and acquiring and retaining customers. But in recent years, a whole new model of organization-building has emerged. Rather than being controlled by corporations — with centralized leadership making all decisions about the product or service, even when using consumers’ data and free, user-generated content — this new model leverages decentralized technologies and brings users into the role of owners through the digital primitive known as tokens.

This new model, known as web3, changes the entire idea of GTM for these new kinds of companies. While some traditional customer acquisition frameworks are still relevant, the introduction of tokens and novel organizational structures such as decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) requires a variety of go-to-market approaches. Since web3 is still new to so many, yet there’s tremendous building in the space, in this article I share some new frameworks for thinking about GTM in this context, as well as where different types of organizations may exist in the ecosystem. I’ll also offer some tips and tactics for builders looking to create their own web3 GTM strategies as the space continues to evolve.

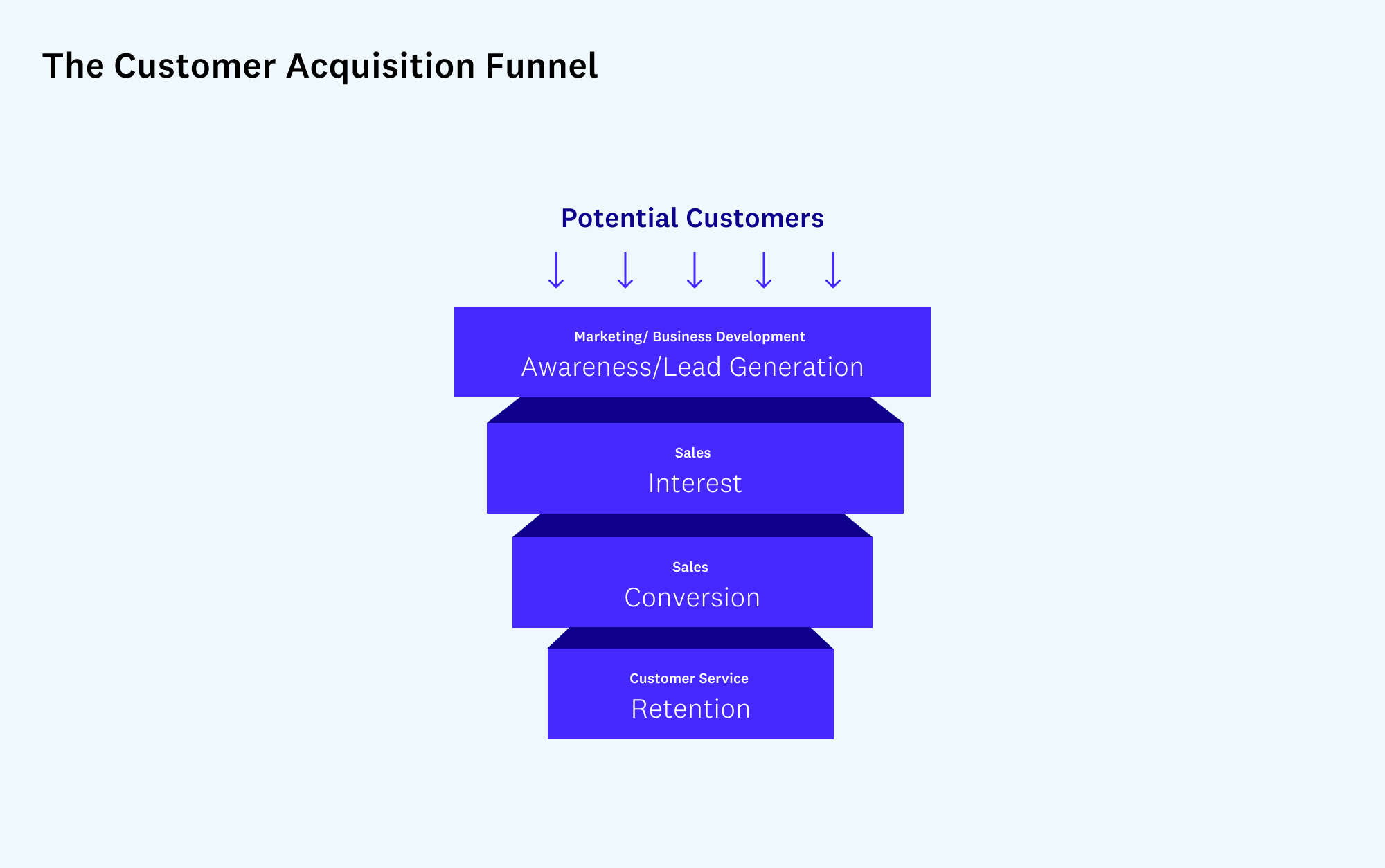

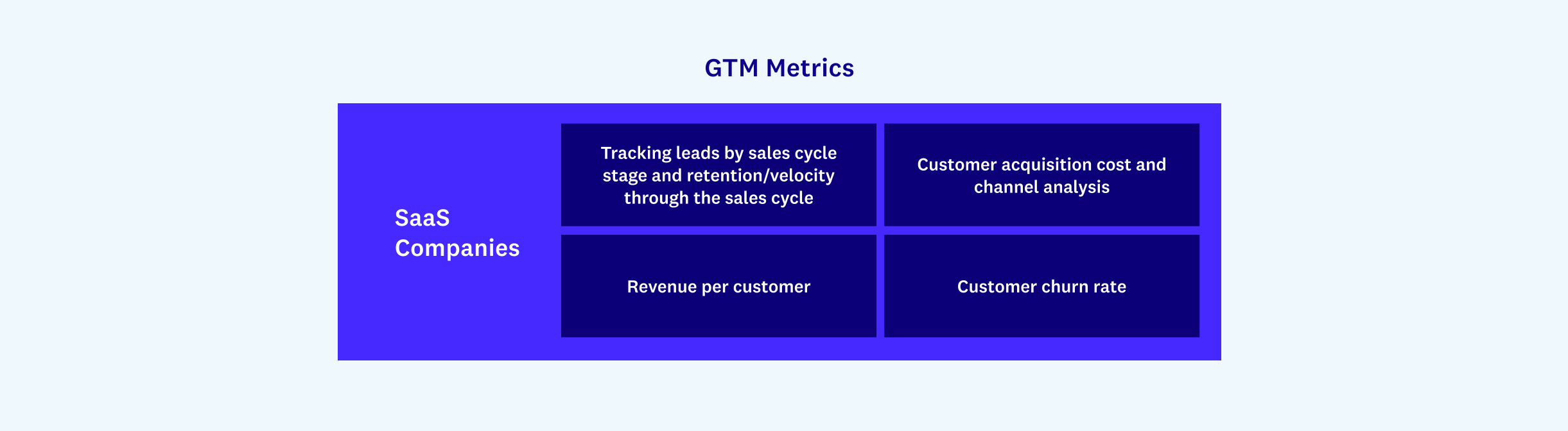

The catalyst of new go-to-market motions: tokens

The concept of the customer acquisition funnel is core to go-to-market, and is very familiar to most businesses: going from awareness and lead generation at the top of the funnel to converting and retaining customers at the bottom of the funnel. Traditional web2 go-to-market therefore attacks the cold-start problem through this very linear lens of customer acquisition, encompassing areas such as pricing, marketing, partnerships, sales channel mapping, and sales force optimization. Success metrics include time to close a lead, site click-through rate, and revenue per customer, among others.

Web3 changes the whole approach to bootstrapping new networks, since tokens offer an alternative to the traditional approach to the cold-start problem. Rather than spending funds on traditional marketing to entice and acquire potential customers, core developer teams can use tokens to bring in early users, who can then be rewarded for their early contributions when network effects weren’t yet obvious or started. Not only are those early users evangelists who bring more people into the network (who would like to similarly be rewarded for their contributions), but this essentially makes early users in web3 more powerful than the traditional business development or salespeople in web2.

For example, lending protocol Compound [full disclosure: we’re investors in this and some of the other organizations discussed in this piece] used tokens to incentivize early lenders and borrowers by providing extra rewards in the form of COMP tokens for participating, or “bootstrapping liquidity,” with a liquidity mining program. Any users of the protocol, whether a borrower or lender, received COMP tokens. After the program launched in 2020, total value locked (TVL) in Compound jumped from ~$100M to ~$600M. It’s worth noting that while token incentivization attracts users, it alone is not enough to make them “sticky”; more on this later. While traditional companies do incentivize employees through equity, they rarely financially incentivize customers in a long-term way (other than through acquisition discounts or referral bonuses).

To summarize: In web2, the primary GTM stakeholder is the customer, typically acquired via sales and marketing efforts. In web3, an organization’s GTM stakeholders include not just their customers/users, but also their developers, investors, and partners. Many web3 companies therefore find community roles to be more critical than sales and marketing roles.

The web3 go-to-market matrix

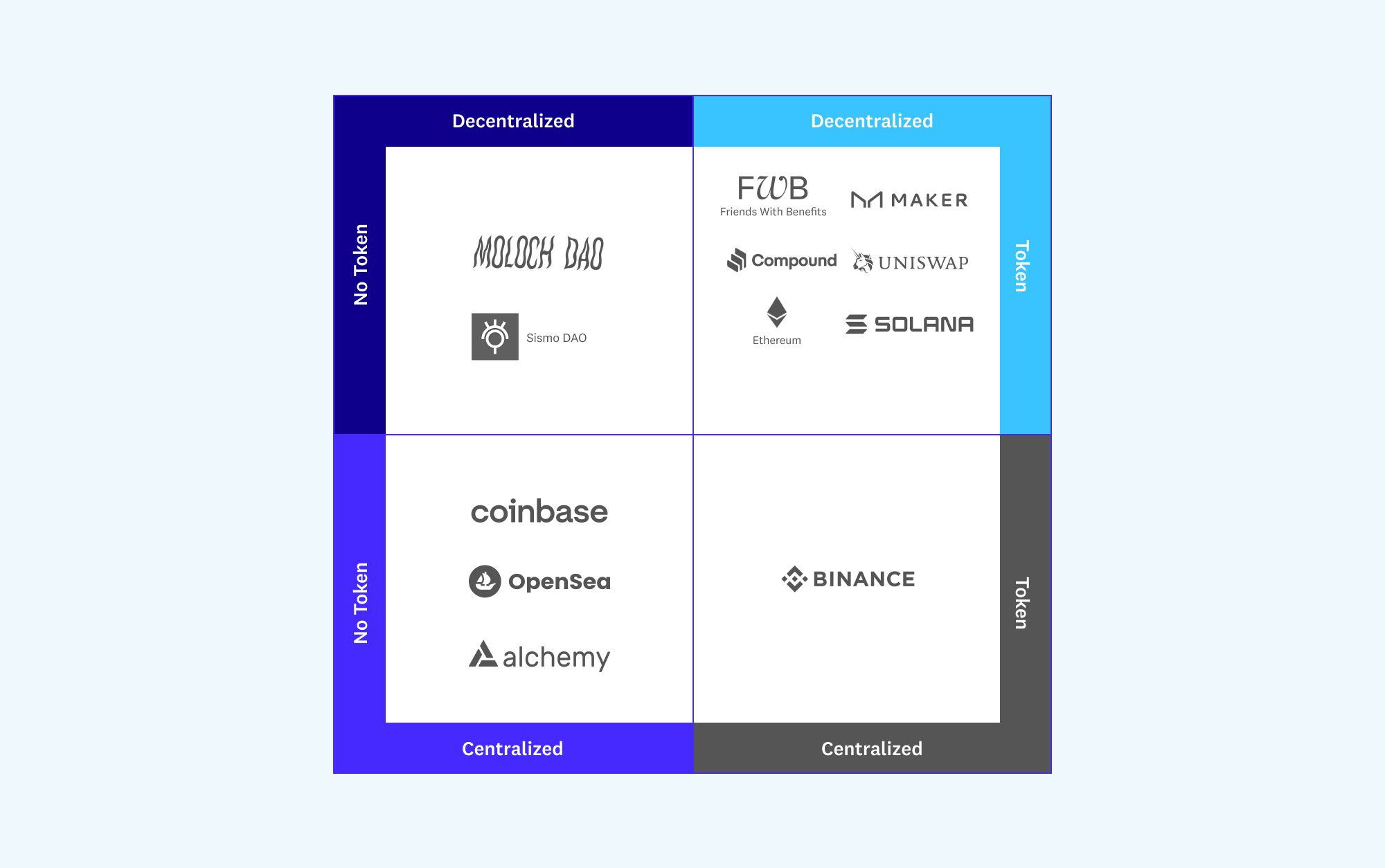

For web3 organizations, GTM strategies depend on where an organization fits in the below matrix, according to its organizational structure (centralized vs. decentralized) and economic incentives (no token vs. token):

Go-to-market differs in each of the quadrants, and can span everything from traditional web2-style strategies to emerging and experimental strategies. Here, I’ll focus on the upper right quadrant (decentralized team with token) and contrast it with the lower left quadrant (centralized team with no token) to illustrate the difference between web3 and web2 GTM approaches.

Decentralized with token

First, let’s look at the upper right quadrant. This includes organizations, networks, and protocols with unique web3 operating models, which in turn require novel go-to-market strategies.

Organizations in this quadrant follow a decentralized model (although they usually start with a core development team or operational staff) and use token economics to attract new members, reward contributors, and align incentives among participants. (For a deeper discussion of web3 business models and the seeming paradox of capturing value, check out this talk from a16z Crypto Startup School.)

The fundamental difference between the web3 organizations in this quadrant and those using a more traditional GTM model involves the key question: What is the product? Whereas web2 companies and those in the lower-left quadrant largely must start with a product that will attract customers (“come for the tools, stay for the network”), web3 companies approach go-to-market through the dual lenses of purpose and community.

Having a product and a solid technical foundation is still important, but it doesn’t have to come first.

What these organizations do need is a clear purpose that defines the reason they exist. What is the problem that they uniquely are trying to solve? This also means more than just raising money based on a white paper and founding team. It means having a strong community — not just being “community-led” or “community-first,” but also being community-owned — blurring the distinction between owner, shareholder, and user. What allows for long-term success in web3 is clear purpose, having an engaged and high-quality community, and matching the right organizational governance to that purpose and community.

Now let’s go deeper into the go-to-market motions in the two major categories of web3 organizations in the upper right quadrant: (1) decentralized applications; and (2) Layer 1 blockchains, Layer 2 scaling solutions, and other protocols.

GTM motions for decentralized applications

“Decentralized applications” covers use cases such as decentralized finance (DeFi), non-fungible tokens (NFTs), social networks, and gaming.

Decentralized Finance (DeFi) DAOs

One major category of decentralized applications are decentralized finance (DeFi) applications, such as decentralized exchanges (e.g., Uniswap or dYdX) or stablecoins (e.g., MakerDAO’s Dai). While they might have similar go-to-market motions as a standard, non-decentralized application, value accrues differently due to the organizational structures and token economics.

Many DeFi projects follow a path where the protocol is first developed by a centralized development team. Following the launch of its protocol, the team often seeks to decentralize the protocol in order to increase its security and to distribute management of its operation to a decentralized group of token holders. This decentralization is typically accomplished through the simultaneous issuance of a governance token; the launch of a decentralized governance protocol (typically a decentralized autonomous organization, or DAO); and the granting of control over the protocol to the DAO.

This decentralization process can involve many different structures and entity forms. For instance, many DAOs do not have any legal entity affiliated with them and operate solely in the digital world, while others use multi-signature (“multisig”) wallets that act at the direction of the DAO. In certain cases, nonprofit foundations are established to oversee future development of the protocol at the direction of the DAO. In nearly all cases, the original developer team continues to operate, in order to act as one of many contributors to the ecosystem created by the protocol as well as to develop supplemental or ancillary products and services. (This white paper contains more details on legal frameworks for DAOs, from taxation and entity formation to operational issues and considerations.)

Here are two popular DeFi examples:

- MakerDAO started as a DAO in March 2015, established a foundation in June 2018, and retired its foundation in July 2021. MakerDAO has a stablecoin, Dai, whose purpose is to enable its users to transact in a fast, low-cost, borderless, and transparent way with a stable unit of value. This could be through purchasing goods and services or engaging with other DeFi applications. It also has a governance token, MKR. The DAO approves various governance changes as well as certain parameters of the protocol’s operation, including the collateralization ratios the protocol uses to mint DAI.

- The Uniswap protocol was launched by a centralized company, but is now owned and governed by the Uniswap DAO, which is controlled by UNI token holders. Uniswap Labs, the creator of the protocol, operates one interface to the Uniswap protocol and is one of many developers contributing to the protocol’s ecosystem.

So what does go-to-market look like here? Take the example of Dai, the algorithmic stablecoin issued and governed by MakerDAO. One goal for most algorithmic stablecoin issuers such as MakerDAO is to generate more usage of their stablecoin in the financial ecosystem. The go-to-market motion is therefore to have it: 1) listed on cryptocurrency exchanges for retail and institutional trading; 2) integrated into wallets and applications; and 3) accepted as payment for goods or services. Today, there are over 400 Dai markets, it is integrated into hundreds of projects, and it is accepted as a form of payment through major commerce solutions like Coinbase commerce.

How did they do it? MakerDAO initially accomplished this through a more traditional business development team that was driving many early partnerships and integrations. However, as it increased its decentralization, the business development function became the responsibility of the growth core unit, a sub-community of Maker token holders often referred to as a SubDAO. Additionally, since MakerDAO is decentralized and its protocol’s operation is trustless and permissionless, anyone can generate or buy Dai using the protocol. And because Dai’s code is open source, developers can integrate it into their apps in a self-service manner. As time went on and the protocol became more self-service — with better developer documentation and more integration playbooks — other projects were able to build off that at scale.

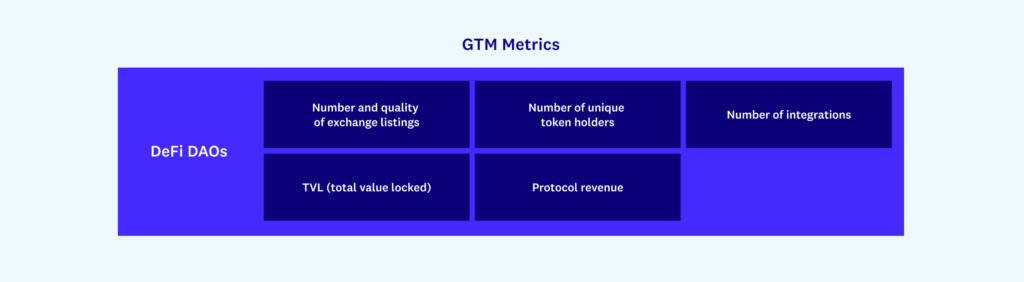

Go-to-market metrics for DeFi DAOs: With new go-to-market strategies for web3 come new ways of measuring success. For DeFi apps, the canonical success metric is the aforementioned total value locked (TVL). It represents all the assets using a protocol or network for things like trading, staking, and lending.

However, TVL is not an ideal metric to measure long-term organizational health and success. Although new DeFi protocols can copy open-source code, offer high yields, and attract significant financial inflows and TVL, this is not necessarily sticky — traders often leave as soon as the next project pops up.

The more critical metrics to track, therefore, are areas such as number of unique token holders; community engagement frequency and sentiment; and developer activity. Additionally, since protocols are composable — able to be programmed to interact with and build on each other — another key metric here is integrations. Number of and type of integrations track how and where the protocol is used in other applications, such as wallets, exchanges, and products.

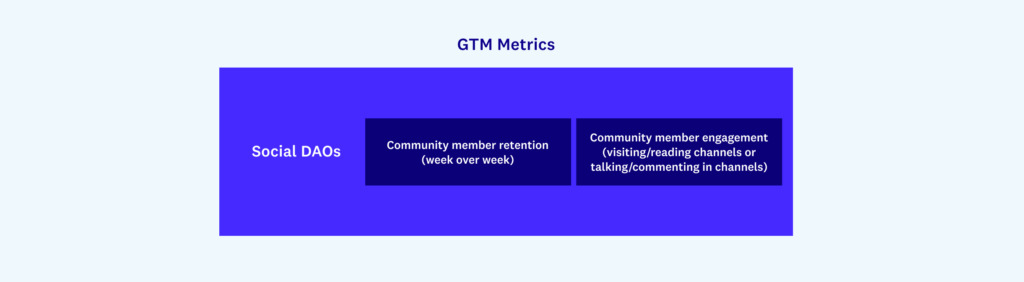

Social, culture, and art DAOs

For social, culture, and art DAOs, go-to-market means building a community with a specific purpose — sometimes even starting as a text chat between friends — and growing it organically by finding other people who believe in that same purpose. But isn’t this “just a group chat” or just like traditional crowdfunding on Kickstarter, for instance?

No, because while organizers of traditional web2 crowdfunding projects may also have a clear purpose, they have to be much more clear about the means of achieving that purpose top-down. The project originators typically outline a detailed breakdown of how funds raised will be used, a clear product roadmap, and a comprehensive timeline. In the web3 model, the purpose is paramount, but the methods are often figured out later — including how funds will be used, the product roadmap, and the timeline.

For instance, with ConstitutionDAO, the purpose was buying a copy of the U.S. Constitution; for Krause House, the purpose is buying an NBA team and pioneering fan governance of a team; for LinksDAO, it is creating a virtual country club with a community of golf enthusiasts; and for PleasrDAO, it is for collecting, displaying, and creatively adding/sharing back to the community NFTs to represent culturally significant ideas and movements.

In the case of ConstitutionDAO, which raised $47M from a community of strangers that came together around this purpose, the entire process came together in a matter of weeks, and started with a clear purpose and raising money for that specific purpose only. ConstitutionDAO did not have much else — no clear roadmap, execution plan, or even a token at that point (it was created after the bid was unsuccessful). Individuals who contributed financially were so aligned with the purpose, and motivated by the community, that they simply wanted to contribute and spread the word, filling Twitter with emoji scrolls that became a meme.

Friends with Benefits is a token-gated social DAO that started as a token-gated Discord server for web3 creatives. In addition to a minimum buy-in of $FWB tokens, which represents membership in the DAO, potential members must apply to FWB through a written application. The community grew, connected in various Discord channels, ran IRL events, and eventually realized that one of the products they could build was a token-gated events app. FWB gives creatives a real stake in the community, while the DAO framework enables large-scale coordination of this decentralized social group to do things like allocate budget and accomplish projects ranging from publishing content to producing events.

Go-to-market metrics for social DAOs: One of the key measures of health of a DAO is quality engagement of the community, which can be measured through the primary communications and governance platforms it uses. For example, a DAO can track channel activity on Discord; member activation and retention; attendance on community calls, governance participation (who is voting on what, and how often); and actual work being done (number of paid contributors).

Other metrics might be net-new relationships built, or measuring trust developed among DAO community members. Although some tools and frameworks do exist here, social DAO metrics are still an emerging space, so we’ll see more tools emerge and evolve here as the space evolves.

Game DAOs

Today, most web3 games, whether play-to-earn, play-to-mint, move-to-earn, or another type, closely resemble popular web2 counterparts — but with two key distinctions:

- The use of in-game assets native to open, global blockchain platforms rather than the closed, controlled economies found in traditional pay-to-own and free-to-play titles; and

- The ability of game players to become true stakeholders and have a say in the governance of the game itself.

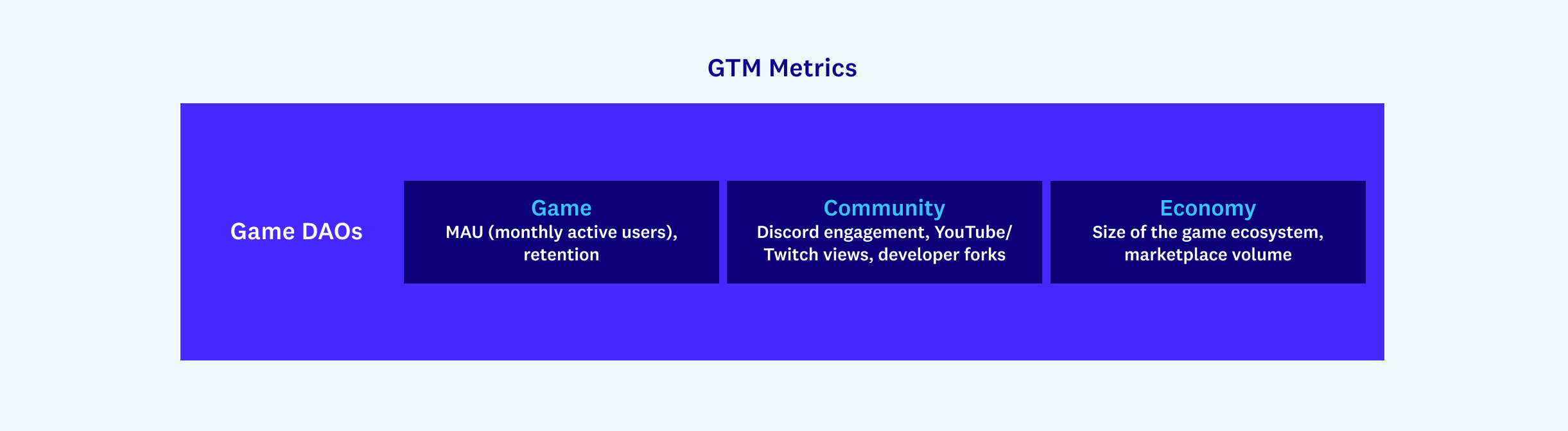

In web3 gaming, go-to-market strategy is built through platform distribution, player referrals, and partnerships with guilds. Guilds such as Yield Guild Games (YGG) allow new players to start playing a game by loaning them game assets that they might otherwise not be able to afford. Guilds choose what games to support by looking at three factors: the quality of the game; the strength of the community; and the robustness and fairness of the game economy. Game, community, and economic health must all be maintained in tandem.

While developers of blockchain-based games might have a lower ownership percentage and/or take rate, by incentivizing players as owners the developers are helping grow the overall economy for all.

But unlike in web2, purpose and community lead. For instance, Loot, a game that started with content first before moving to gameplay, is an example of purpose and community, rather than product, driving GTM. Loot is a collection of NFTs, each known as a Loot bag, which have a unique combination of adventure gear items (examples include a dragonskin belt, silk gloves of fury, and an amulet of enlightenment). Loot essentially provides a prompt — or building block primitive — upon which games, projects, and other worlds can be built. The Loot community has created everything from analytics tools to derivative art, music collections, realms, quests, and more games, inspired by their Loot bags.

The key idea here is that Loot grew not due to an existing product that users flocked to, but because of the idea and lore it represented — an open, composable network that welcomed creativity and incentivized users through tokens. The community makes the product — it’s not the network making the product in hopes it will attract a community. As such, a key metric here would be the number of derivatives, for instance, which could be considered even more valuable here than traditional metrics would.

GTM motions for Layer 1 blockchains and other protocols

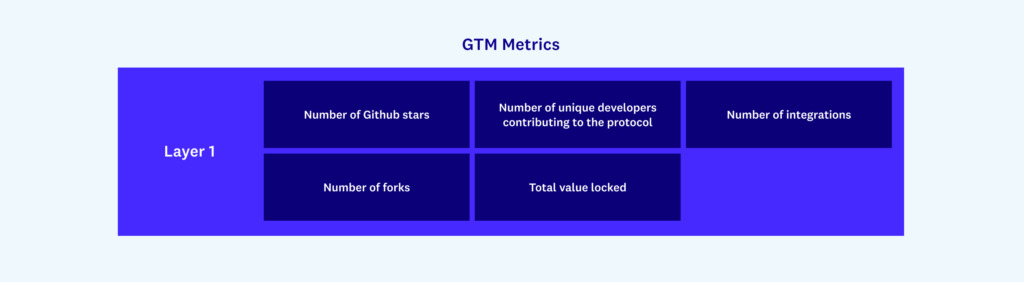

In web3, Layer 1 refers to the underlying blockchain. Avalanche, Celo, Ethereum, and Solana are all examples of Layer 1 blockchains. These blockchains are all open source, so anyone can build on top of them, replicate or alter them, and integrate with them. Growth of these blockchains comes from having more applications built on top of them.

Layer 2 refers to any technology that operates on top of an existing Layer 1 to help solve scalability challenges with Layer 1 networks. One type of Layer 2 solution is a rollup. Layer 2 rollups do just that — they “roll up” transactions off chain and then post the data back onto the Layer 1 network via a bridge. There are two primary categories of Layer 2 rollups. The first, optimistic rollups, “optimistically” assume the transaction is honest and not fraudulent via a fraud proof. The second, zk rollups, use “zero knowledge” proofs to determine the same. The majority of these Layer 2 solutions are currently being developed for Ethereum and do not yet have their own token, but we will discuss them here as their go-to-market success metrics are similar to those of the other networks in this category.

Additionally, protocols can be built on top of other L1s or L2s, with the Uniswap protocol, for example, supporting Ethereum (L1), Optimism (L2), and Polygon (L2).

Growth of Layer 1 blockchains, Layer 2 scaling solutions, and these other protocols can come from forks, which are when a network is replicated and then altered. For example, Ethereum, a Layer 1 blockchain, was forked by Celo. Optimism, a Layer 2 scaling solution, was forked by Nahmii and Metis. And Uniswap was forked to create SushiSwap. While this may initially seem negative, the number of forks that a network has can actually be a measure of success — it shows that others want to copy it.

These examples and mindsets all focus on the upper right quadrant, decentralized networks with tokens — broadly speaking, the current most advanced examples of web3. However, depending on the type of organization, there is still a fair amount of blending of web2 GTM strategies and emerging web3 models. Builders should understand the range of approaches as they begin to develop their go-to-market strategy, so let’s now take a look at a hybrid model that blends web2 GTM with web3 GTM strategies.

Centralized and no token: The web2-web3 hybrid

Many of the companies in this lower left quadrant (centralized team with no token) provide entry points and interfaces for users to access web3 infrastructure and protocols.

In this quadrant, there is significant overlap in go-to-market strategies between web2 and web3 — especially in the areas of SaaS and marketplaces.

Software-as-a-service

Some companies in this quadrant follow the traditional software-as-a-service (SaaS) business model, for example Alchemy, which provides nodes-as-a-service. These companies offer infrastructure-on-demand through various tiers of subscription fees, determined by considerations such as amount of storage needed, whether nodes are dedicated or shared, and monthly request volume.

The SaaS business model generally requires a traditional web2 go-to-market motion and incentives. Customer acquisition is through a combination of product-led and channel-led strategies:

Product-led user acquisition is focused on getting users to try the product itself. For example, one of Alchemy’s products is Supernode, an Ethereum API targeted at any organization that is building on Ethereum but that doesn’t want to manage its own infrastructure. In this case, customers would try Supernode via a free tier or freemium model, and those customers would recommend the product to other potential customers.

In contrast, channel-led user acquisition is focused on segmenting out different customer types (for example, public-sector vs. private-sector customers), and having sales teams aligned to those customers. In this case, a company might have a sales team focused solely on public-sector customers such as government and education, and would deeply understand the needs of that type of customer.

I’m providing an overview in this article to help explain the difference between web2 and web3 go-to-market strategies, but it’s important to note that developer-focused outreach and developer relations — including developer documentation, events, and education — is also very important here.

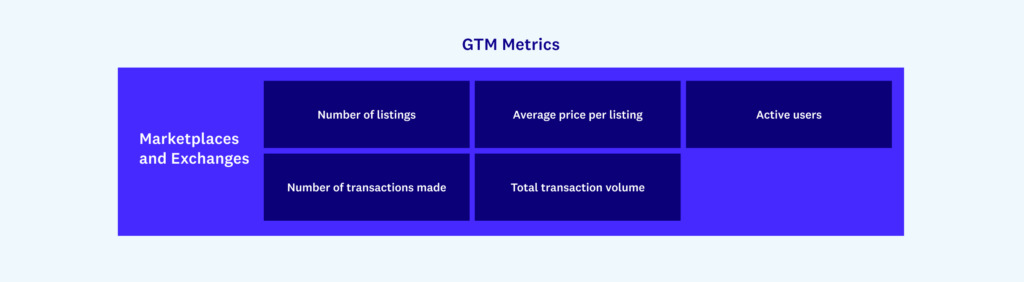

Marketplaces and exchanges

Other companies in this quadrant lean on the relatively familiar-to-consumer models of marketplaces and exchanges, such as peer-to-peer horizontal NFT marketplace OpenSea and cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase. These businesses generate revenue — the “take” — based on a transaction fee (typically a percentage of the transaction), which is similar to the business models of classic web2 marketplaces such as eBay and Amazon.

For these types of companies, revenue growth comes from growing the number of listings, the average dollar value of each listing, and the number of users of the platform — all of which lead to increased transaction volume, while benefiting users in terms of variety, marketplace liquidity, and more.

A key go-to-market motion here is increasing channel distribution by partnering with other platforms to show a selection of items. This is similar to the Amazon affiliate program, in which bloggers can link to their favorite items, and any purchases made through those links give the blogger a commission. But a key difference from web2 is that web3 structures allow for royalty distributions back to the creator in addition to the affiliate fee. For example, OpenSea offers the traditional affiliate sales channel through their White Label program, in which purchases made through a referral link give a percentage of the sale to the affiliate, but it also allows for royalties, in which creators can continue to earn a percentage of any secondary sales. (This web3 feature is uniquely made possible by crypto because smart contracts can encode the percentage arrangement up front, blockchain tracks provenance, and more.)

Since creators now have an opportunity to continue to monetize their work through the secondary markets — value they previously could not see, let alone capture, in web2 systems — they are incentivized to continue to promote the marketplace. Creators become evangelists as well.

GTM tactics

Now that I’ve shared an overview of key mindsets and example use cases, let’s take a look at specific go-to-market tactics often seen in web3 organizations. These are the core ingredients, not a complete playbook, but can still help builders entering and exploring the space understand the tactics and options.

Airdrops

An airdrop is when a project distributes tokens to users to reward certain behavior that the project wants to incentivize, including testing the network or protocol. These can be distributed to all existing addresses on a given blockchain network, or targeted (such as to specific key influencers); often, they are used to solve the cold start problem — to bootstrap early adoption, award or incent early users, and more.

In 2020, Uniswap airdropped 400 UNI to anyone who had used the platform. In September 2021, dYdX airdropped DYDX to users. More recently, ENS conducted an airdrop to anyone with an ENS domain (a decentralized .eth domain); the airdrop was conducted in November 2021, but anyone who owned an ENS domain before October 31, 2021, was/is eligible (until May 2022) to claim $ENS tokens, which provide holders with governance rights with respect to the ENS protocol.

In the non-fungible token space, airdrops for NFT projects are also growing in popularity to help with giving more people access and other reasons. One recent notable airdrop was from the Bored Ape Yacht Club, a collection of 10,000 unique NFTs; on August 28, 2021, BAYC created the corresponding Mutant Ape Yacht Club. Each of the BAYC token holders received a mutant serum, allowing them to mint 10,000 “mutant” apes, and additionally a new 10,000 mutant apes became available for new entrants. Because there were different types of serums, serums could only be used once, and since a Bored Ape could not use multiple serums of the same tier, serums added a new scarcity model.

The rationale behind the creation of the MAYC was to “reward our ape holders with an entirely new NFT” — a “mutant” version of their ape — while also allowing newcomers into the BAYC ecosystem at a lower tier of membership. This maintains accessibility to the broader community, while not diluting the exclusivity of the original set or having those original owners feel like their contributions were downgraded. (Another way of addressing accessibility is with NFT fractionalization, where an NFT has multiple owners.) The MAYC floor price, or lowest listed price for a MAYC, is consistently lower than the BAYC floor price, but owners essentially have the same benefits.

These airdrops were done retroactively to reward NFT holders or network and protocol users (as was the ENS airdrop), but airdrops can also be used as a proactive GTM motion to generate awareness for a specific project and to encourage people to check it out. Since information is public on the blockchain, a new project can airdrop to, for example, all the wallets using a specific marketplace, or all the wallets holding a specific token.

In any case, projects should clearly articulate their overall token distribution, breakdown, and plans before conducting the airdrop. There are many examples of airdrops being used for nefarious purposes and of airdrops gone wrong. In addition, airdrops of tokens can be deemed to be securities offerings in the United States, so projects should consult counsel prior to engaging in any such activity.

Developer grants

Developer grants are grants made from a protocol’s treasury to individuals or teams who are contributing in some way to improving the protocol. This can serve as an effective GTM mechanism for DAOs, since developer activity is such an integral part of a protocol’s success. Examples of projects and protocols with developer grants include Celo, Chainlink, Compound, Ethereum, and Uniswap.

But grants can be given for everything from protocol development to bug bounties, code audits, and other activities beyond coding. Compound even has a type of grant related to business development and integrations, funding any integrations that grow the usage of Compound. An example of this is their funding of a grant that integrated Compound with Polkadot.

Memes

Viral images with text overlays are another GTM tactic for web3 organizations. Given the complexity and breadth of the cryptocurrency ecosystem and the short attention spans of social media users, memes allow information to be rapidly conveyed. Memes can also signal belonging, community, goodwill, and more in a highly information-dense way.

The NFT project Pudgy Penguins, a collection of 8,888 penguins, started due to its meme-ability. The primary drop of the collection sold out in 20 minutes, and the collection was featured in major media outlets, which in turn helps mainstream such projects. The social display and community element of “PFP” (profile picture) collections — in web3 this is coming about as NFTs displayed as an owner’s profile picture on social media — also allow for this virality. Twitter recently rolled out a feature allowing users to prove their ownership of an NFT via hexagonal-shaped profile pictures linking to OpenSea’s API.

Owners with large social media followings generate awareness of a project when they change their profile picture to one from that project, and project owners typically follow all other owners of the same project. These moves can in turn also beget other memes, as in the case of Crypto Covens and the “web2 me vs. web3 me” meme where users came to display their witches alongside their actual faces, signaling identity, belonging, and more.

***

So what does this all mean for web3 founders? The biggest mindset shift is moving from planning to something more like gardening.

In web2 companies, founders not only set a top-down vision but are responsible for growing a team and planning and executing against that vision. In web3, founders take on more the role of a gardener, helping cultivate and nurture potentially successful products but also setting up the space for it all to happen. While web3 founders still set the purpose of the organization, and its initial governance structure, the governance structure itself might quickly lead to new roles for them. Instead of optimizing for headcount growth or revenue and profitability, founders might be optimizing for protocol usage and quality of community. In addition, following any decentralization, founders must adapt to environments in which no hierarchical power structures exist, and where they are one of many actors championing the success of a given project. As such, prior to decentralizing, founders should ensure that they are setting up their project for success in such an environment.

I witnessed some of this firsthand when I was chief of staff to Tony Hsieh, former CEO of Zappos.com, an e-commerce company now owned by Amazon. The company experimented with more decentralized (compared to only top-down) governance structures beginning in 2014, including the self-organized management system known as “holacracy.” Holacracy involved a hierarchy of work rather than of people, and had mixed results. But Hsieh offered a useful metaphor when comparing his role as being the cultivator of a greenhouse of plants (in the holacracy model), rather than being the best plant. He had said he needed to be the “architect of the greenhouse” — setting the right conditions to enable all theother plants to flourish and thrive.

Today, Alex Zhang, Mayor of Friends with Benefits (FWB), the social DAO with a fungible token, echoes the sentiment, describing that his job “is not to set a top-down vision” but to facilitate the creation of “frameworks, permits, and regulations for community members” to approve and to build on top of. Where a web2 leader would be focused on updating the product roadmap and driving toward new product launches, Zhang considers himself more of a gardener rather than a top-down builder. His role includes watching the FWB “neighborhood” (in this case, Discord channels) and curating it by retiring channels with little traction and helping support and grow channels that have momentum. By creating a framework for these channels — and playbooks for channel success (such as a mix of activity, clear leadership, and governance structures) — Zhang becomes more of an educator and communicator.

In the case of founders of NFT projects, their role is primarily as originators and temporary stewards of intellectual property (IP). Yuga Labs, the creators of Bored Ape Yacht Club, wrote, “We see ourselves as temporary stewards of IP that is in the process of becoming more and more decentralized. Our ambition is for this to be a community-owned brand, with tentacles in world-class gaming, events, and streetwear.” Owning an NFT — whether it’s an image, a video or sound clip, or another form — conveys to the owner all the rights associated with the NFT. As the NFT is bought and sold, that ownership is transferred — and as ecosystems grow around the NFT, those benefits go to the NFT owner, not just the founding team of the NFT project.

NFT ownership can also be about community-driven licensing and community-driven content (unlike traditional IP franchises). An example here is Jenkins The Valet, an NFT avatar from the BAYC collection (specifically, Ape #1798) that signed with Creative Artists Agency (CAA) for representation across various forms of media. Jenkins was created by Tally Labs, the group that owns Ape #1798. Tally Labs decided to imbue the ape with its own brand and backstory, and turned the notion around of an NFT’s statistical rarity being the main determinant of its price and success. They then created a way for others to participate in creating content around Jenkins through a “writer’s room” NFT, where, for example, community members were able to vote on the genre of the first book.

So much more is possible here; we have yet to see what more is possible as more people embrace crypto and decentralized technologies and web3 models. Traditional web2 GTM frameworks are a useful reference, and offer some helpful playbooks — but they are just a few of the many frameworks available for web3 organizations. The key difference to remember is that the goals, growth, and success metrics of web2 and web3 are often not the same. Builders should start with a clear purpose, grow a community around that purpose, and match their growth strategies and community incentives — and with them, the go-to-market motions — accordingly. We will see a variety of models emerge, and look forward to observing and sharing more here.

Thanks to Justin Paine, Porter Smith, and Miles Jennings for their contributions to this article.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.