Many have made the case for decentralization, including us on several occasions — decentralization is a key benefit of blockchain technology, and has the potential to address many current social challenges online. But blockchains only make decentralization possible, they do not make it inevitable.

Regulatory approaches to decentralization will therefore play a significant role in determining whether decentralization succeeds or fails, either outright prohibiting it or incentivizing it. And the role decentralization should play in the regulatory frameworks for crypto continues to be hotly contested. Bad actors have a number of reasons to rally against it — decentralization guards against entrenched interests, regulatory capture, value extraction, and get-rich-quick schemes. Even the best industry actors have legitimate doubts — is decentralization too amorphous of a concept, and one that can be too easily manipulated by overzealous regulators, as we saw the past few years?

But abandoning decentralization would miss the unique technological characteristics that make blockchains, blockchains — the very features that distinguish them from proprietary software. Those characteristics of blockchain technology — autonomy, transparency, and trustlessness — can mitigate risks to investors and consumers (in addition to offering other benefits like ownership, choice, etc. to users). As a result, blockchains justify new regulatory approaches. Not accounting for these core principles would leave the industry unmoored from any unifying and consistent principle under the law, leaving decisions to whim and not logic.

Decentralization must be incentivized, not ignored. So I argue in this piece that we must start with a better definition of decentralization — one that moves us beyond the ambiguities that have caused unintended consequences, and that could simplify things for both policymakers and builders.

Defining decentralization

Defining decentralization can’t be an amorphous, blurry Rorschach test that anyone can interpret any way they like based on what they want to see in it. We know where that path leads — enforcement agencies like the SEC, CFTC, FinCEN, and DOJ have weaponized expansive and ambiguous definitions of decentralization to go after good actors and bad actors alike. Perverse incentives abound, nowhere more so than at the SEC, which focused the past few years on persecuting the founders who continue to build and benefit tokenholders, over those that take the money and run.

A better, simpler, and less amorphous approach is possible. Within a given regulatory framework, the meaning of decentralization should be constrained to the unique and objectively measurable characteristics of blockchain technology that mitigate the risks a regulatory scheme is intended to address. This core principle can be used to define decentralization for legal regimes that apply to money transmission, custody, securities laws, commodities laws, and beyond. In this post, I apply the principle to digital assets — exploring the relationship between decentralization and the risks arising from digital assets, and then proposing a constrained approach to decentralization.

My argument is simple: For digital assets, decentralization should focus on the absence of control, not on curtailing ongoing developer efforts. Such an approach could be used to protect investors, while still fostering innovation; limit digital assets being used to issue ordinary securities that circumvent securities laws; and provide a framework that’s easier for regulators to apply and for builders to follow.

Mapping token risks to decentralization under securities laws

The relationship between decentralization, and risks arising from digital assets, is complex. Holders of digital assets are subject to a variety of risks; there are a myriad of decentralization factors that interplay with such risks; and such factors are often subjective (and their importance relative to one another varies by project).

Nevertheless, these token risks are primarily a function of a digital asset’s: (1) token characteristics, and (2) trust dependencies.

Token characteristics

The risks inherent to a digital asset are a function of its characteristics. Digital assets are software and can be programmed to represent anything — a digital store of value like Bitcoin, a consumptive asset like Ethereum, a stablecoin like USDC, and even a share of stock.

Decentralization is most relevant to the risk profile of digital assets that have securities-like features, but are not securities. These digital assets are commonly referred to as “network tokens” — digital assets that are speculative in nature and whose value is substantially derived from the operation of any blockchain or smart contract protocol (e.g., BTC, ETH, SOL, UNI, etc.).

Network tokens do not provide the owner with any financial interest in another person, or enforceable contractual rights with respect to the ongoing efforts of another person — but their value is often tied to a blockchain-based network. This relationship can be as simple as the token price being driven by market demand for the blockchain network, or be as complicated as the token price being directly tied to the revenue-generating activity of the network. In all such cases, this relationship introduces risks that implicate securities laws.

Network tokens also often have utility — as they can easily be designed to function as a currency in connection within a blockchain-based product or service — such as to pay for gas fees, to acquire other assets, or to stake as collateral. But “utility” alone does not meaningfully change the risk profile of network tokens. For example, a share of Amazon stock would not be exempt from securities laws simply because Amazon began accepting such shares as payment for Amazon Web Services (AWS). Similarly, digital assets should not be exempted merely due to the presence of utility.

Trust dependencies

Trust is a hallmark of most types of securities: Owners of shares trust a company’s management team to drive share value or return profits. Owners of notes trust the borrower to return their funds with interest. Commodities, on the other hand, are inherently trustless — the holder of a commodity is not dependent on any single actor to drive value.

This difference in trust dependencies leads to the different treatment of offers and sales of securities and commodities under U.S. law, because the presence of trust dependencies influences the relative risk of information asymmetries arising with respect to each asset.

But securities laws are not designed to alter the risk profile of securities to turn them into commodities. Rather, they are designed to protect investors investing in securities — primarily by requiring disclosures to limit risks of information asymmetries that arise due to the trust dependencies of securities. Per the SEC’s 2019 Framework, absent disclosures, “…significant informational asymmetries may exist between the management and promoters of the enterprise on the one hand, and investors and prospective investors on the other hand. The reduction of these information asymmetries through required disclosures protects investors and is one of the primary purposes of the federal securities laws.”

Commodities trading does not require such disclosures, as the risk of information asymmetries is low.

Digital assets are different from other assets, because they can have trust dependencies comparable to both securities and commodities. Here are two examples to help demonstrate this:

- If Amazon were to issue a digital asset that derived value from the continued operation of AWS, such an offering would be indistinguishable from a securitization subject to securities laws.

- Bitcoin derives its value from the ongoing operation of the Bitcoin network, but because the operation of that network is not dependent on any actor, its trust dependencies are similar to a commodity.

The critical difference between these two extremes is the relative risk of information asymmetries arising:

- In the Amazon example, the risk is significant. Even if Amazon made no promises regarding the continued operation of AWS, and the AWS token provided no rights, title, or interest in Amazon itself — the AWS token would have similar trust dependencies and corresponding information asymmetry risks as many securities. Applying securities laws could help reduce such risks.

- In the Bitcoin example, no such trust dependencies exist; the risk of information asymmetries is minimal. Applying securities laws here would not meaningfully change the risk profile of the asset.

To sum up: The trust dependencies of an asset dictate the potential risk of information asymmetries arising, which informs whether or not securities laws would be helpful to apply.

Blockchain-based networks are different from proprietary software here, because they are uniquely positioned to eliminate trust dependencies and reduce the risk of information asymmetries. Transparent, verifiable, and publicly accessible blockchain data mean that all transactions and value accrual occur onchain — visible for anyone to audit and verify. This is the functional equivalent of audited and unassailable financial statements.

However, there are two other primary trust dependencies that are not inherently eliminated by blockchains:

- Control. Whoever exerts control over a system (a company, a network, etc.) or its underlying asset, controls the risks associated with that asset — exposing holders to several risks, including information asymmetries, market manipulation, conflicts of interest, and value extraction.

- Ongoing Efforts. Being dependent on the ongoing efforts of a small number of actors to maintain and develop a system exposes holders of the system’s underlying asset to several risks, including information asymmetries.

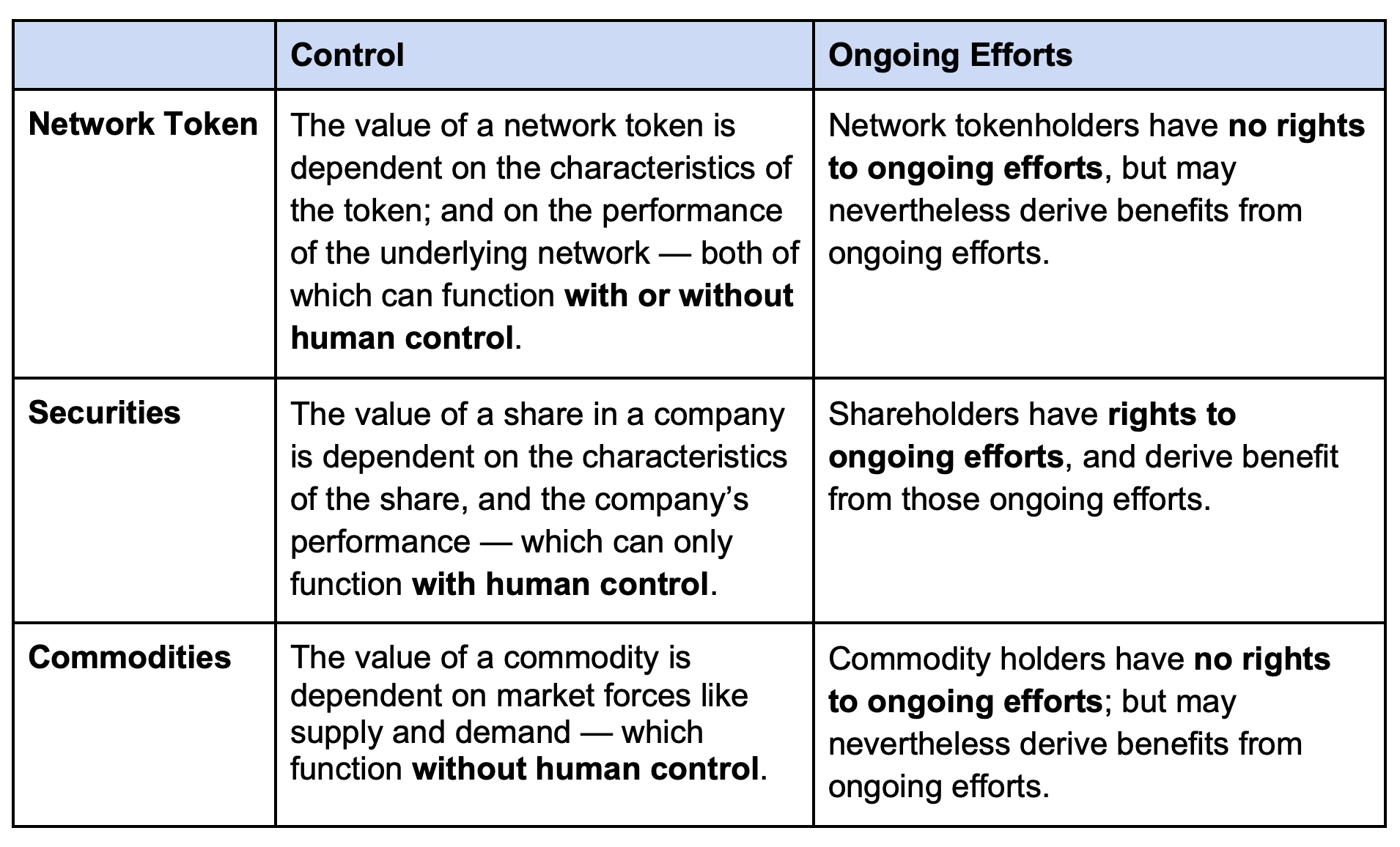

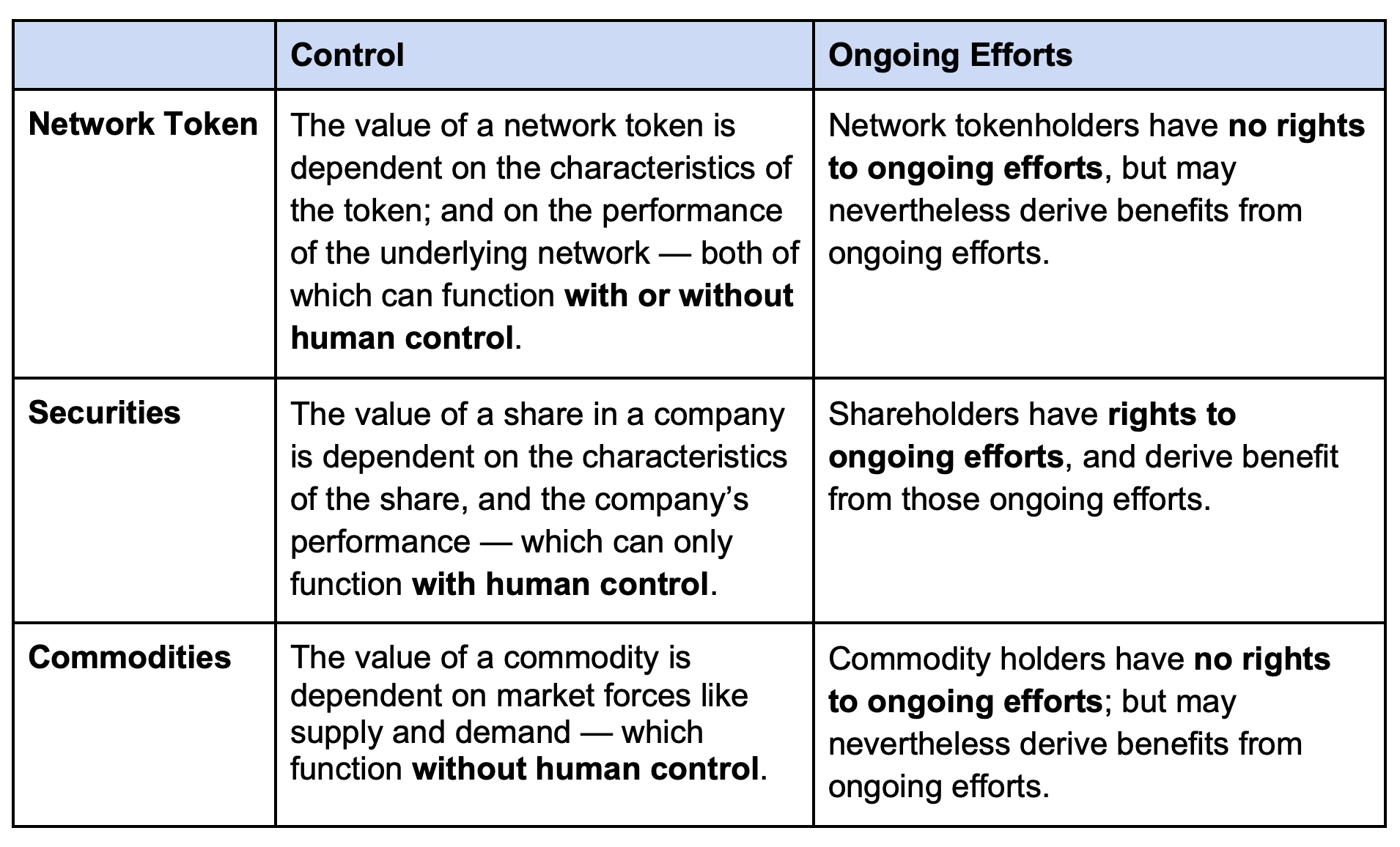

Across network tokens, securities and commodities, the role “control” and “ongoing efforts” differ as follows:

Network tokens, like commodities, derive their value from systems that can operate without human intervention. This means they are capable of operating in a manner that precludes any party from unilaterally affecting or structuring the risk associated with the network’s token. The elimination of this trust dependency again distinguishes network tokens from securities.

Returning to the Amazon example: The presence of control means Amazon can simply stop operating AWS, unilaterally changing the risk profile of the hypothetical AWS token. Applying securities laws is warranted here, to guard against the risk of information asymmetries that may arise as a result of that control.

But in the case of Bitcoin: No such controlling party exists, so applying securities laws here is unwarranted.

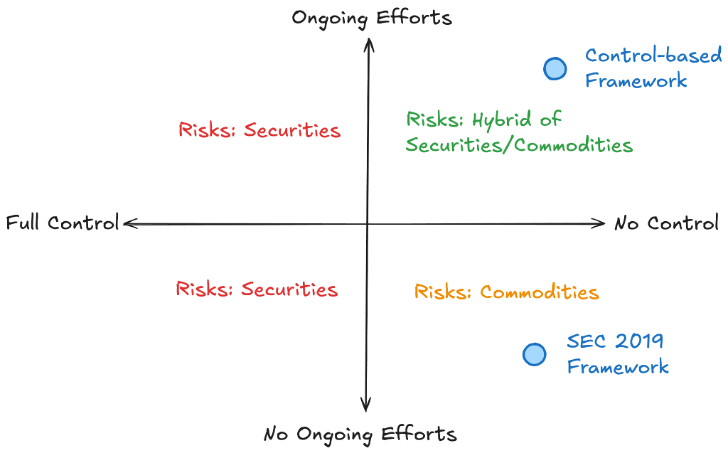

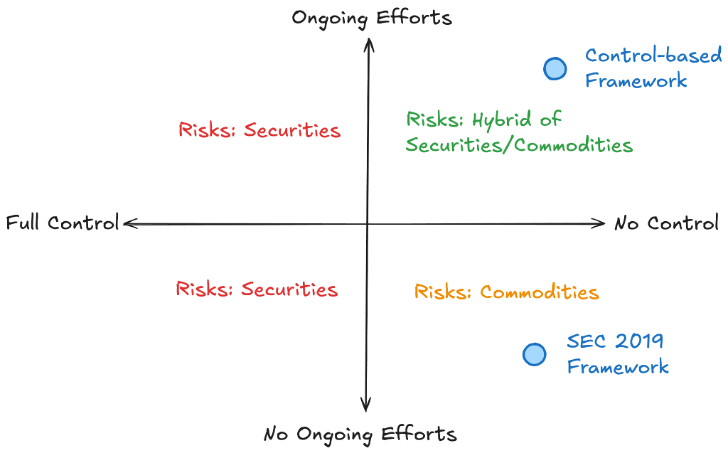

The SEC’s 2019 framework sought to reduce the risk of information asymmetries arising from both control-based and ongoing efforts-based trust dependencies. It reasoned that:

- where a network and its token are controlled and being actively developed through ongoing efforts, the risk of information asymmetries may be comparable to a share of stock;

- but where a network and its token are not controlled and there is no reliance on ongoing efforts, the risk of information asymmetries is more similar to an ordinary commodity.

With the substantial legal benefit of avoiding securities laws now being tied to the SEC’s 2019 definition of decentralization, many developers responded by reducing elements of control over their projects and by decentralizing their ongoing efforts. However, in the hands of the previous administration, this approach resulted in several unintended consequences:

- The use of an expansive and subjective definition of decentralization has made the 2019 framework incredibly difficult to enforce effectively, but very easy to weaponize by overzealous regulators against good actors.

- The incorporation of “ongoing efforts” into the definition of decentralization created a paradox: It incentivized builders to forestall or obfuscate ongoing development efforts post-token launch, thereby introducing greater operational and execution risks to token holders rather than reducing such risks.

Both of these problems can be solved with a new, simpler approach — one that pairs a more constrained definition of decentralization with a light-touch disclosure regime.

A new path forward: A simpler, and easier to apply, definition of decentralization

First, the definition of decentralization should be constrained to mean the absence of control, thereby addressing risks arising from control-related trust dependencies.

Using a rules-based approach, legislation or regulators could establish objective criteria capable of being easily evaluated — determined by anyone at any time, based on a review of a project’s codebase and ledger. Among the criteria that should be considered are whether the network is: open source, functional, verifiable, autonomous, permissionless, non-custodial, credibly neutral, distributed, economically independent, and immutable.

Collectively, these characteristics are not possible for closed and proprietary networks controlled by corporations. But they are fundamental to blockchains.

Second, a fit-for-purpose disclosure regime could build on the transparency inherent with blockchains to mitigate risks of information asymmetries arising from ongoing development efforts. Such disclosure criteria should focus on information most relevant to blockchain projects, as identified in Token Safe Harbor Proposal 2.0 and FIT21, to name a few examples.

While simple, the use of a two-pronged approach is a significant improvement. The 2019 framework sought to subject projects to securities laws if they operated anywhere other than the lower right quadrant below (no control/no ongoing effort) — which is what led to abuse by regulators and perverse incentives for developers. But this new two-pronged approach would more appropriately provide projects with a pathway to operate in the upper right quadrant (no control/with ongoing effort) — where those network tokens have a risk profile that reflects a hybrid of commodities and securities.

Critically, both strategies — constrained definition of decentralization, and light disclosure — are necessary to achieve a better way. Relying on decentralization alone has failed. And while relying on disclosure obligations alone could eliminate risks of information asymmetries, disclosure obligations do not change the inherent risks of network tokens — in other words: Without decentralization, the economic reality, and risk,of many network tokens may be comparable to securities, thereby making it difficult to credibly argue that special treatment under securities laws is justified.

Instead, pairing decentralization and disclosure leads to the optimal outcome: Network tokens are differentiated from securities with objective and easily measurable criteria; builders are empowered to build out in the open; and participants are provided with transparent disclosures.

This approach also provides a much more practical and tangible “decentralization” target for regulators to focus on, one that is also more consistent with other regulatory regimes:

Further, having more clarity and certainty around the meaning of decentralization will enable policymakers to design mechanisms that effectively incentivize decentralization; facilitate progressive decentralization; guard against bifurcated markets; and most importantly, encourage builders to build — rather than engage in “decentralization theater” (or worse, abandon projects). Better yet, the use of objective and easily measurable criteria means all of this can be achieved at scale.

* * *

Decentralization should be defined and used as a tool that maximizes the benefits that blockchains deliver, while reducing risks to users — across every intersection of law and blockchains/ crypto. The definition of decentralization should not be a tool for persecuting developers. While decentralization is hard, defining it doesn’t have to be. We should start with control. From there, we can rely on builders and others in the trenches to define objective criteria for “control” based on their experience and learnings from the battle-hardened blockchain systems in the space.

This isn’t an academic or wonky debate. The ambiguities of decentralization have encumbered the blockchain industry and slowed the pace of innovation to date. Clear and objective approaches would enable the industry to overcome these obstacles, creating an environment where builders can thrive, participants can engage with confidence, and the power of decentralization is unleashed to the benefit of all.

For digital assets, that starts with redefining decentralization as the absence of control.

Editor: Sonal Chokshi

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investment-list/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures/ for additional important information.