“If you fail to plan, you plan to fail.”

Benjamin Franklin wasn’t talking about startup founders when he said that (as far as we know), but he may as well have been. There are many, many things that founders, especially those in crypto, can’t control: Markets are volatile, regulations are evolving, and expectations are high.

That’s why it’s so important to focus on what you can control, which is where operating plans come in. It may not sound glamorous, but an operating plan is one of the most controllable, leverageable tools you have, and it’s how you turn your vision into velocity — without burning your runway or your team.

In concept, an operating plan is simple — it’s everything your business is doing: What tasks exist? Who’s doing them? What goals are they working toward? How much does it all cost? How are you measuring results? The answers to those questions, though, can get complicated, which is why having a plan to organize them is key.

Even if you’ve never come up with an operating plan for a business, you’ve probably done it for your personal life. For example, if you want to run a marathon, you need a training plan that organizes the months leading up to the race day. How long are your runs? When will they get longer, and by how much? What routes will you follow? How will you rest and recover? How will you treat an injury? In the business world your “race day” might be a product launch, an IPO, or any other big goal — the principles are the same.

But don’t confuse an operating plan with a strategic plan. The strategic plan defines the business’s big picture, the vision you sell investors on. The operating plan is how you’ll execute on that vision in practical terms; it translates the strategic plan into actionable specifics of people, cost, and timelines. To have a healthy, viable business, you need both kinds of plans.

Now, let’s dive into what your operating plan should take into account.

Creating an operating plan

To start, focus on four operational pillars: people (Who is responsible?); timing (When will each task be completed?); cost (What’s the budget?); and measurement (How will progress be evaluated?).

You’ll iterate on the operating plan over time, so don’t overthink the first draft. There are lots of best practices — lots of frameworks, lots of expensive consultants you could hire to help. But the core job is to clearly articulate who’s doing what in the company — and you can get that down on paper yourself, even if you need help polishing it later. For now, just aim for clarity and structure in your operating goals for a period of time.

Importantly, your plan should involve making tradeoffs. The company can’t do everything, so tradeoffs are healthy — and they should be hard, fostering good discussion among your leadership team about where to focus and where not to. No matter how successful the company becomes, tradeoffs will always be part of the equation, and constraint has the power to drive better decisions.

Three common mistakes

As you map out the operating plan, there are three common mistakes to be aware of.

1. Don’t be overly optimistic about timing and expected results. Information is changing constantly, so your plan needs to be agile and flexible. Beware dependencies: We want to launch product A in order to launch product B or We have to hire two engineers to create that new feature or Revenue is going to increase by this amount, as long as we hire a marketing person.

Layering these kinds of factors into your operating plan can be tempting, but dependencies create problems when milestones are missed. If it takes a while to hire those two engineers, you might risk missing the deadline for the feature they were going to create. So it’s OK for your operating plan to be optimistic, but it should be realistic, too. Give yourself room to change tack when circumstances call for it — and don’t forget to adjust your downstream timelines accordingly.

2. Don’t try to do too much at once. Founders tend to have lots of ideas for the business, but time and resources are finite, and pursuing all your ideas simultaneously will damage your cash burn and the team’s focus.

Instead, strategically sequence your activities. In other words, think about how different opportunities and capabilities can unlock other opportunities and capabilities. Maybe launching a certain product can bring you new users, which gives you a chance to leverage those users. Maybe investing in a certain technology can open up new revenue possibilities. Consider how best to order the company’s activities, and how to allocate time and resources accordingly.

Of course reality is messier than a plan. As a founder, you’re the most in touch with a set of opportunities related to your product. The temptation will be to go after many of those opportunities, partially because you can see how big the market is for each of them but also because the core product may not be working how well or how fast you want it to, so you want to give yourself multiple pathways to success. The tough reality is that small teams can typically only execute on one thing really well. Diluting your focus, while it may seem appealing, usually results in suboptimal execution on the most important thing.

To assess the business’s focus, ask yourself two questions: What is the business’s current top priority? and What are people spending most of their time on? If the answers aren’t identical, you might have a problem.

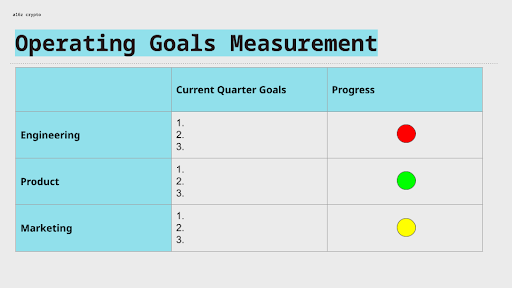

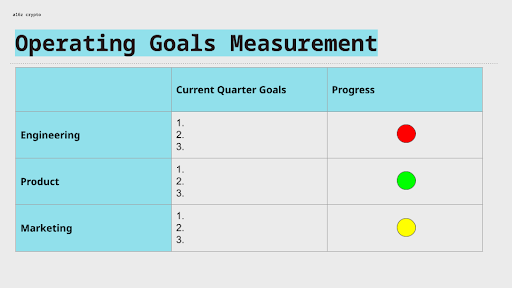

3. Your company needs measurable success metrics. You can have the most brilliant operating plan in the world, but unless you can monitor what the business is doing, the whole plan can go in the garbage. Why? If you don’t know how to measure success, you won’t know how to measure (or even be aware of) failure either, which means you’ll struggle to adapt to challenges and setbacks. The metrics don’t have to be complicated; even red/yellow/green status indicators can work well. But you do need metrics.

Remember: whatever you incentivize drives people’s behavior. Be thoughtful about whether your metrics are driving the best outcomes for the business. As a simple example, you probably want to tie people’s incentives to the results they’re producing, not just how many hours they work.

What to know about budgeting

A budget is a key piece of any operating plan — the plan has to address “What does all this cost?” — so there are some budgeting tips every founder should know.

Most companies spend most of their money on employees. That isn’t always the case, but it’s a good rule of thumb, especially because founders sometimes underestimate the fully burdened cost of bringing on more people. It’s not just salaries, benefits, and payroll taxes to think about; there are also costs for hardware, software, license seats, travel, and whatever else your people need. Many expenses scale directly with the number of employees, so model them that way.

And on a related note, don’t forget to budget for equity like you budget for cash. Managing equity could be a separate article, but when you create your hiring plan you’ll want to budget the associated equity you plan to grant as well. If your project grants tokens to employees, you’ll want to apply the same principles. Overall, it’s important to have a holistic and intentional compensation philosophy. Mistakes made early tend to compound.

Separate fixed and variable costs to understand your flexibility. You need to know the dials in the budget you can and can’t adjust. Let’s say you had to cut 30% of your costs next week — do you know where those cuts will come from? Or let’s say the company is growing and you want to push on the gas pedal — do you know where it makes sense to do that? Getting that understanding can be hard in early-stage companies because you don’t have as many variables. But the better you understand those budget dials, the more intuitive these decisions will be.

Bonus tip: Remain as agile as you can by negotiating with vendors and service providers to avoid multiyear contracts whenever possible.

Scenario planning is your friend. Any budget you make is going to be wrong; it’s just a question of by how much. That’s true even in mature companies because there are just too many factors for the budget to cover. So rather than getting fixated on one ideal version of the company’s future, use scenario planning to get comfortable with a range of futures, and assign a probability and confidence interval to each one. What kinds of factors could surprise you? What changes could upend the company’s current model? If you’re facing regulatory uncertainty, for example, what could the business look like with different regulatory outcomes? View your budget as a learning and planning tool for discussing and organizing opportunities and uncertainties.

Don’t get below six months of cash runway. You never want to be surprised when it comes to your cash burn, but that happens to founders all the time. Imagine your company has two years of runway but there’s no operating plan to guide you. Maybe you get to the end of the year and realize you hired five more people than you thought you would, plus you’re six months behind on the product. Suddenly, you only have six months of runway left. Unless you’re monitoring the cash burn well, you’ll spend all your mental energy on fundraising or cutting costs. And even if you secure other funding, closing it can take longer than you’d like, racking up legal fees in the meantime — not to mention that you’ll lose leverage the closer you are to running out of cash.

The key to avoiding a runway problem is to stay on top of your budget. Don’t outsource this responsibility too much as a founder. While you can outsource the actual work to others on your team, you should still be having a monthly conversation to compare the expected burn and actual burn for the month. Was the actual materially off from the expected? If so, is there something to learn or adjust? Were you thinking about any costs incorrectly? Or was it a one-time issue?

One helpful tool for founders is “zero-based budgeting”. Currently, lots of companies prepare next year’s budget by using the current budget and adding or subtracting 10%. While it’s an easier approach than some methods, it discourages critical thinking about what the business needs now. With zero-based budgeting, you start with a blank page and carefully consider what the company will actually spend next year. The benefit is, you have to justify each expenditure rather than just rolling things forward from last year. That can help you target your budget to where the business is today.

A note on treasury management, especially for crypto founders: It’s worth establishing an investment policy that provides parameters on how to manage your treasury. While your risk tolerance can often be a function of your runway, always keep in mind that your first priority is capital preservation.

What operating mode are you in?

There’s no right or best framework to use for your operating plan. Whatever you choose, it just has to help you address those key plan components: who’s doing what, by when, how much does it cost, and how are you measuring it?

Before choosing a framework, though, you should identify what operating mode you’re in, since the mode informs your priorities. Here’s a series of questions for doing that:

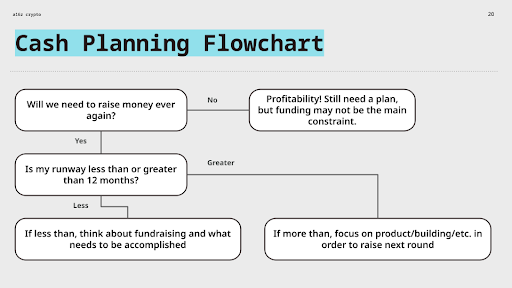

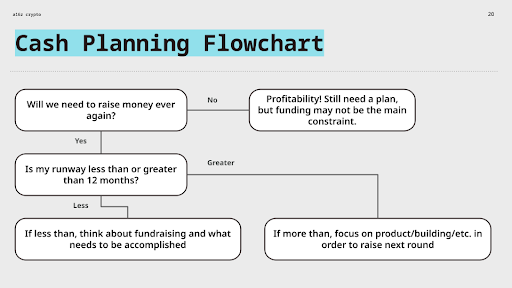

1. Will you need to raise money ever again?

The answer is probably “yes,” since most early-stage venture-backed companies will raise money again, but there are some exceptions. If you’re already profitable, great — you still need an operating plan, but funding may not be its main constraint. If you aren’t profitable yet, keep going with the other questions.

2. Is your runway more than or less than 12 months?

The key idea here is, if your runway is longer than 12 months, fundraising may not need to be in your plan for the year. Maybe your priority is building your product or hiring a team. But if your runway is shorter, then the operating plan should include fundraising, cutting costs, or strategic partnership and/or investment opportunities or all of the above. You also probably want to take a critical look at your spend to find ways to improve it.

3, If you need to raise money, what do you need to accomplish?

You’ll have to figure out what milestones must be achieved to convince investors to fund your next round. The right milestones depend on the business and what sort of round you want to raise, so it’s a good conversation to have with your investors. For example, you may think that launching a product will lead to more funding, but they might want to see product-market fit first.

Next, what resources do you need to achieve those milestones? Look at who you need to hire, any other steps you have to take, and how long you think it will take. Cost it out into a spreadsheet — does your cash in the bank cover what you need? If not, look at the variables you can adjust to make the numbers work. Would sequencing your activities differently help? Switching the business’s current priorities?

Once you’ve nailed down the resources, consider how much runway you’d get by hiring or investing in them. Then ask yourself: Is that runway sufficient given the cash we have today? If it is sufficient, you’re in a strong position to develop the operating plan. If not, you’ll need to iterate on the plan by revisiting where you’re hiring, investing, or focusing.

Finally, come up with some metrics to monitor the operating plan, so you’ll know whether it’s working. Importantly, there has to be a cadence to the monitoring so that it’s happening regularly.

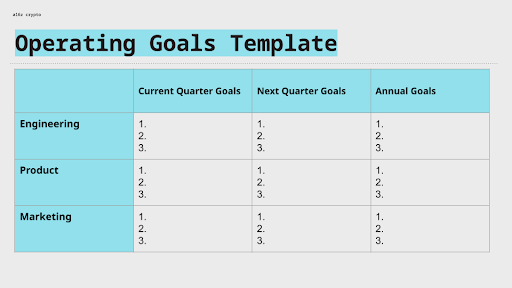

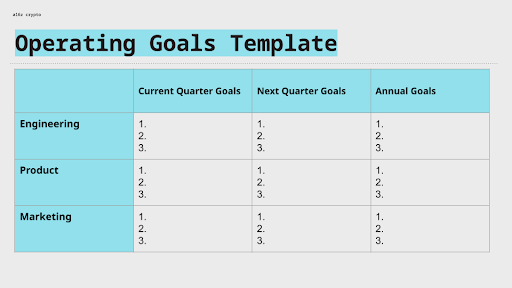

Operating goals template

The worksheet below gives you some boxes to start sketching out ideas for your operating goals. One method is to start with your goals for the year, then work your way backward to what needs to happen each quarter, for each function, or even for each person, depending on the size of your company. Half the battle is to just get your ideas on paper, since the more you try to keep the whole operating plan in your head, the more likely you are to miss or forget things.

Below an example of a simple measurement system for tracking progress on your goals. With the red/yellow/green metrics, you could bring them to a weekly leadership meeting to give a quick update on the goals that are going well and the ones you’re concerned about. In this example, you might share that product is fine, marketing had a hiccup but you’re not worried about it, and engineering hit a serious problem that the team should discuss. Obviously, the system isn’t complicated, which is the point — find ways to monitor the operating plan and hold people accountable that aren’t too cumbersome.

***

Creating an operating plan for your business is a critical step — but don’t overthink it. Focus on substance over form and making sure you can answer simple questions such as who is doing what, by when, and how much does it cost. Once you do that, you have something to measure yourself against and keep track of how the business is pacing according to plan. And stay on top of your runway.

***

Emily Westerhold is a partner on the crypto team, focused on finance and operations advisory. Before joining Andreessen Horowitz, she was most recently the CFO of VSCO, where she spent 7 years helping to build and scale the company and still serves on the board. Prior to VSCO, she worked in various finance and accounting roles and began her career at PwC.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investment-list/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures/ for additional important information.