The Fourth Amendment

The Fourth Amendment protects our privacy rights in material that we keep private. The government can’t search our homes or computers, for instance, unless it has a warrant based on specific probable cause to believe that the searches will uncover evidence of crime.

Nor can the government just summon us to court to provide testimony that will yield such evidence of crime: The Fifth Amendment’s privilege against self-incrimination protects against that.

On the other hand, the Fourth Amendment has been read as providing little protection for material that we turn over to third parties — even to one trusted third party, such as a bank. This “third-party doctrine,” which is the key to the government’s power to gather information from financial intermediaries, lets the government easily get transaction information from businesses, without a search warrant or probable cause. (This is supplemented by requirements, which the Court has upheld, that banks keep records of financial transactions.[1])

The third-party doctrine, for better or worse, is well-established. But when technological innovation — such as DeFi (decentralized finance) — cuts out the third party, the government can no longer use the third-party doctrine to monitor such transactions.

The question then becomes: May the government restrict such DeFi tools, and force people to use third-party intermediaries, precisely to take advantage of the extra surveillance power that the third-party doctrine would provide?This question has taken on added importance in the context of emerging web3 technologies, with implications for coders, customers, and entrepreneurs.

The relationships between coders and users

Consider one of the proposals that has been floating around in recent years: Requiring developers of DeFi products (whom we’ll call “coders” for short) to adhere to “know your customer” rules for users of those products. Right now, the developers lack any existing business relationship — and thus any information-gathering capabilities — with regard to their end users.

But say the government mandates that coders track their users’ behavior. Such a mandate would essentially outlaw creating intermediary-free, off-the-shelf DeFi protocols and code that any third party can use. Some say that portions of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (HR 3684), signed into law in mid-November, could be read by the government as imposing such an obligation on coders.[2]</span

Say the government mandates that coders track their users’ behavior. Such a mandate would essentially outlaw creating intermediary-free, off-the-shelf DeFi protocols and code that any third party can use.

I think this is the wrong way of reading the statute, but say that the statute is indeed so read, precisely to block the development of technologies that the government sees as too effective at protecting financial privacy. DeFi platforms, a government enforcement agency might believe, are facilitating tax evasion; by compelling DeFi coders to produce tax returns for transfers occurring pursuant to the protocol, the agency would force the coders to abandon their plans of providing hands-off, off-the-shelf DeFi technology. Instead, the coders would have to become exchanges, which would have to deal directly with their users and collect their users’ information.

Such a potential reading of the statute would deliberately force people to shift away from conduct protected by strong Fourth Amendment protections (transactions that don’t involve third parties) to conduct protected by weaker Fourth Amendment protections (transactions that do involve third parties). In what follows, I’ll explain why I think this sort of restriction of privacy-protecting technologies might itself violate the Fourth Amendment.

Evolving technology, lagging law

The premise of the third-party doctrine is that “the issuance of a subpoena to a third party to obtain the records of that party does not violate the [Fourth Amendment] rights” of the person about whom the records are kept.[3] The legal system “has a right to every man’s evidence,”[4] including evidence from businesses that have learned something about you in the course of their business. If you bring such financial intermediaries into your financial transactions, your privacy becomes vulnerable.

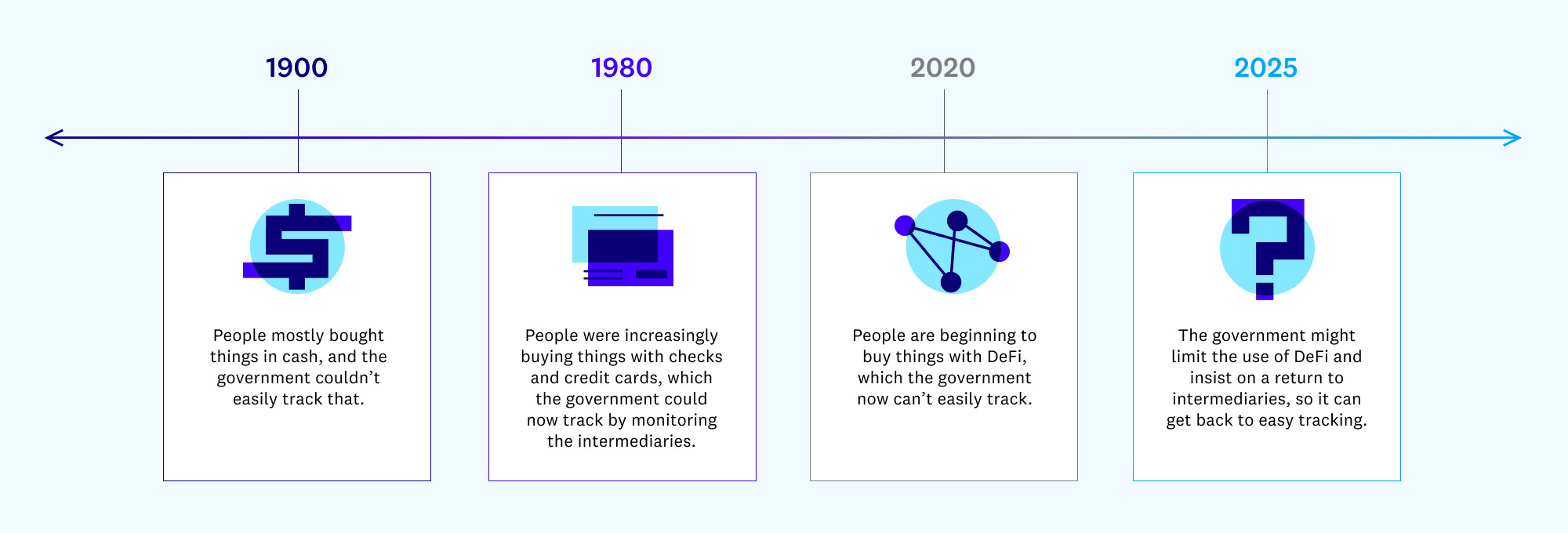

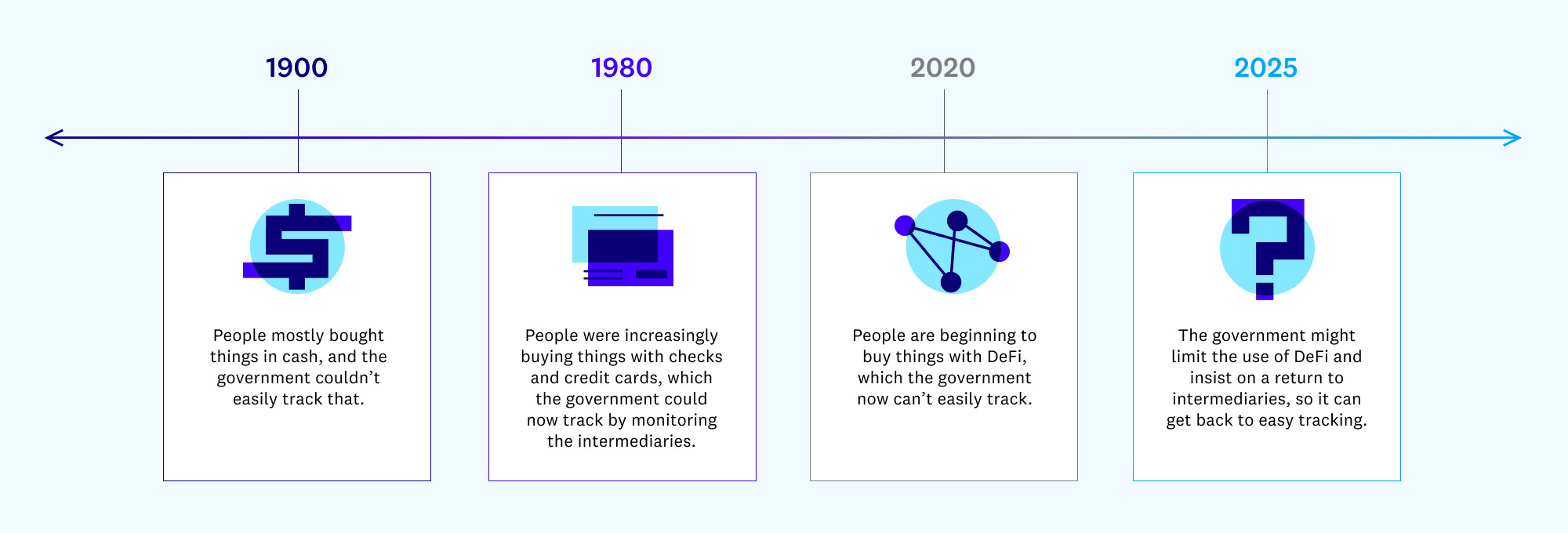

And technology has exacerbated this vulnerability. When our transactions were mostly in-person cash transactions, there were no financial intermediaries for the government to subpoena. The government could theoretically subpoena the people with whom we transacted, but those people would often be hard to find, or they might not remember who paid cash for something three months before. Technology has immeasurably extended our commercial opportunities, by letting us deal with people remotely; but since that has required checks, credit cards, and similar mechanisms, it has brought in intermediaries. The result: Much more convenience but much less privacy.

The balance of power is shifting back from the government to individuals. And, unsurprisingly, the government is thinking about how to shift that balance back to itself.

Now comes modern financial technology: By letting us cut out the intermediary, it lets us enjoy the ancient benefits of cash, together with the modern benefits of electronic transactions. The balance of power is shifting back from the government to individuals. And, unsurprisingly, the government is thinking about how to shift that balance back to itself. To offer a stylized timeline:

A right to use rights-protecting technologies?

Yet a mandate that coders monitor who is using their code — essentially a prohibition on privacy-protection financial technologies — may well violate the Fourth Amendment. That conclusion is itself a reason to avoid misreading HR 3684 as covering coders: When there are “competing plausible interpretations of a statutory text,” “the canon of constitutional avoidance” adopts “the reasonable presumption that Congress did not intend the alternative which raises serious constitutional doubts.”[5] And that conclusion may also offer a basis for invalidating any statutory provisions that are indeed read this broadly.

Injecting third parties precisely to facilitate surveillance

To begin with, if the government seeks to stop the creation and distribution of intermediary-less DeFi code,[6] the government would be doing so precisely to bring back the third party — not for the sake of financial necessity (the way that a third party had historically been necessary for electronic transactions), but for ease of surveillance.[7] The premise of the third-party doctrine is that “a person has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties,” because he “assume[s] the risk that the [third party] would reveal to police the [information].”[8] If the government takes away the option of a private transaction, and requires that information be turned over to third parties, then the turning over of the information is no longer truly voluntary. Nor are such people assuming the risk of disclosure: the risk is being thrust upon them by government mandate.[9]

If the government seeks to stop the creation and distribution of intermediary-less DeFi code, it would be doing so precisely to bring back the third party — not for the sake of financial necessity but for ease of surveillance.

Likewise, the third-party doctrine rests on the theory that, by handing over information to a third party, a person “is deemed to surrender any privacy interest he may have had” in that information.[10] Thus, by banning privacy-protecting technologies, precisely to bring third parties back into the transactions, the government would be requiring people to “surrender” their “privacy interest[s]” that would otherwise be protected by the Fourth Amendment — something the government may not require.

To offer an analogy: The Court has held that, when a driver of a car is arrested, (1) the police may search the car’s passenger compartment for weapons that might be within the driver’s reach without needing to show probable cause, but (2) they may not search any separately locked trunk. Imagine that a state required that all cars on the roads lack a separate trunk (i.e., that they be SUVs, hatchbacks, or station wagons), precisely so drivers have fewer Fourth Amendment protections.[11] Perhaps, by following the analogy to the broad reading of HR 3684, imagine that a state required unworkable record-keeping obligations of car manufacturers who make cars with separate trunks: Say that manufacturers were ordered to report the names and addresses of everyone who drives such a trunk-less car, even though the manufacturers lack any business relationship with many drivers (who might buy or borrow a car from a third party).

Imagine that a state required that all cars on the roads lack a separate trunk, precisely so drivers have fewer Fourth Amendment protections.

Though there is no precedent squarely on point, this would likely be unconstitutional, as a circumvention of the normal Fourth Amendment rules. Just as the government can’t, for instance, circumvent the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition on “be[ing] compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against [your]self” by coercing you to testify in a civil case and then using the information in a criminal case,[12] so it shouldn’t be able to circumvent the Fourth Amendment’s protection of privacy by denying you privacy-protecting tools.

Constitutional rights to technologies that protect other constitutional rights

Indeed, courts have long recognized that certain technologies are necessary to protect constitutional rights, and that banning the use of the technologies would therefore violate those rights. For instance, lower courts have held that the First Amendment includes the right to video-record government employees (such as police officers) in public places.[13] The courts began with the premise that the public has a First Amendment right to “access … information about their officials’ public activities.”[14] And they therefore held that the First Amendment must likewise protect the technology necessary to effectively gather that information — technology that lets one “record what there is the right for the eye to see or the ear to hear,” “corroborat[ing] or lay[ing] aside subjective impressions for objective facts.”[15]

Of course, through much of the nation’s history, such spontaneous video-recording was simply technologically unavailable, at least to ordinary laypeople. But once the technology has been invented, the government may not forbid it and thereby force people to rely on technologically unaided perception.

Courts have long recognized that certain technologies are necessary to protect constitutional rights, and that banning the use of the technologies would therefore violate those rights.

Similarly, the right to use contraceptives is actually based on a right to make “decision whether or not to beget or bear a child.”[16] But effectively exercising that right requires technological help — whether from centuries-old technologies like condoms, or from much more recently invented and sophisticated pharmaceuticals — and therefore such technology is also protected by the underlying right. The use of a latex device or a pill is not itself a “decision … not to beget … a child”: the decision precedes the use of the device. Yet the use of such technologies facilitates reproductive autonomy, and restricting the use of such devices or pills substantially burdens people’s right to turn their decisions about family and parenthood into reality.

Constitutional rights to technologies that protect constitutional privacy rights

The same logic applies to informational privacy, and not just the “right of privacy” protected by the Court’s decisions about contraceptives. The Fourth Amendment secures the privacy of people’s communications, so long as the people actually do keep the communications private and don’t turn over information to third parties whom the government could subpoena. To effectively exercise this right, and to avoid forfeiting it by introducing a third party, people may use Fourth-Amendment-protecting technologies, such as cryptographic tools that coders develop to cut out the middleman. Banning such technologies (or requiring that they be set up in a way that does forfeit the Fourth Amendment right) would violate the Fourth Amendment privacy right.

These matters are not settled. Courts might be reluctant to reject the government’s arguments, especially when they are couched in terms of perceived public safety and law enforcement need.

For example, some states have antimask laws, which ban people from appearing in public wearing masks; the laws were largely created to stop terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, but apply equally to all masked protesters. Some courts have struck down such laws, concluding that masks are important devices for protecting privacy even in public places, and for encouraging people to speak without fear of governmental or private-sector retaliation for their unpopular opinions.[17] But other courts have upheld antimask laws.[18] It’s thus impossible to predict with confidence how courts would react to constitutional challenges to a hypothetical law that bans use of other privacy-protecting technologies, such as various DeFi tools.

My point here is simply that the argument in favor of such constitutional challenges is strong, and may prevail. Courts should at least avoid interpreting laws to create such a constitutional problem.[19] And Congress should avoid creating laws that pose the problem.

***

[1] E.g.,California Bankers Ass’n v. Shultz, 416 U.S. 21 (1974).

[2]See § 80603 (amending 26 U.S.C. § 6045(a)).

[3] United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 444 (1976).

[4] Branzburg v. Hayes, 408 U.S. 665, 688 (1972).

[5] Clark v. Martinez, 543 U.S. 371, 381 (2005).

[6] Cf. Peter Van Valkenburgh, Electronic Cash, Decentralized Exchange, and the Constitution (“In effect, the regulator would be ordering these developers to alter the protocols and smart contract software they publish such that users must supply identifying information to some third party on the network in order to participate . . . .”).

[7] This would be analogous to the government’s periodic attempts to limit the use of encryption. In the 1990s, the government sought to implement (and perhaps eventually mandate) the “Clipper chip”: a device that allowed encrypted communication, but required the encryption keys to be “escrowed” in some place where the government could then access them. More recently, in the late 2010s, federal law enforcement officials called for technology companies to implement similar key escrow facilities, so that (for instance) the government would always be able to unlock the data in your cell phone (assuming law enforcement got a warrant or a similar judicial authorization). This was referred to as the “going dark” debate: law enforcement was concerned that encryption could allow criminals and terrorists to entirely defeat the government’s surveillance and search techniques. See Rianna Pfefferkorn, The Risks of “Responsible Encryption”, Ctr. for Internet & Soc’y paper (Feb. 2018)

But at least the Clipper chip and key escrow facilities appeared to contemplate that the government could use escrowed information only with a warrant based on probable cause — trying to ban DeFi in order to make sure that financial transactions are routinely reported to the government would be a means to avoid the warrant and probable cause requirement.

[8] Smith v. Maryland, 422 U.S. 735, 744 (1979) (emphasis added); see also United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 442 (1976) (holding that people “lack . . . any legitimate expectation of privacy concerning the information kept in bank records” because they “contain only information voluntarily conveyed to the banks”); id. (stressing that “[t]he depositor takes the risk, in revealing his affairs to another, that the information will be conveyed by that person to the Government”).

[9] Cf. Peter Van Valkenburgh, Electronic Cash, Decentralized Exchange, and the Constitution (“If users do not voluntarily hand this information to a third party because no third party is necessary to accomplish their transactions or exchanges, then they logically retain a reasonable expectation of privacy over their personal records and a warrant would be required for law enforcement to obtain those records.”).

[10] United States v. Flores-Lopez, 670 F.3d 803, 807 (7th Cir. 2012); United States v. Wurie, 728 F.3d 1, 16 (1st Cir. 2013).

[11] Restrictions on overly tinted windows may be constitutional, but they are justified by the need “to ensure a necessary degree of transparency in motor vehicle windows for driver visibility,” Klarfeld v. State, 142 Cal. App. 3d 541, 545 (1983) (quoting 49 C.F.R. § 571.205 S2 (1982)); People v. Niebauer, 214 Cal. App. 3d 1278, 1290 (1989) (noting that certain levels of tinting are “permitted on certain windows not required for driver visibility”).

[12] McCarthy v. Arnstein, 266 U.S. 34, 40 (1924); cf. Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347, 360, 364-65 (1915) (striking down a grandfather clause that was a clear attempt to evade the Fifteenth Amendment’s ban on discrimination based on race in voting qualifications); State v. Morris, 42 Ohio St. 2d 307, 322 (1975) (holding that private searches are not covered by the Fourth Amendment, unless they are orchestrated by the government “with[] intent to evade constitutional protections”).

[13] Fields v. City of Philadelphia, 862 F.3d 353 (3d Cir. 2017); Turner v. Lieutenant Driver, 848 F.3d 678 (5th Cir. 2017); ACLU of Illinois v. Alvarez, 679 F.3d 583 (7th Cir. 2012); Glik v. Cunniffe, 655 F.3d 78, 82 (1st Cir. 2011); Smith v. City of Cumming, 212 F.3d 1332 (11th Cir. 2000); Fordyce v. City of Seattle, 55 F.3d 436 (9th Cir. 1995).

[14] Fields, 862 F.3d at 359.

[15] Id.

[16] Carey v. Population Servs. Int’l, 431 U.S. 678, 685 (1977).

[17] See American Knights of the KKK v. City of Goshen, 50 F. Supp. 2d 835, 839 (N.D. Ind. 1999); Ghafari v. Municipal Court, 87 Cal. App. 3d 255, 261 (1979) (challenge brought by protesters who opposed the Iranian government); Aryan v. Mackey, 462 F. Supp. 90, 92 (N.D. Text. 1979) (likewise).

[18] See Church of American Knights of the KKK v. Kerik, 356 F.3d 197, 208-09 (2d Cir. 2004); State v. Berrill, 474 S.E.2d 508, 515 (W. Va. 1996); State v. Miller, 398 S.E.2d 547, 553 (Ga. 1990).

[19] See supra note 5 and accompanying text.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.