Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) investing in crypto assets have suffered from both a lack of regulatory clarity and limited viable custodial options. Adding another layer of complication, crypto assets bear ownership and transfer risks that are unlike assets for which RIAs have previously been responsible. RIA’s internal teams — operations, compliance, legal, and others — make a great deal of effort to find a willing third-party custodian that meets expectations. Despite that effort, RIAs are sometimes unable to find one at all, or to find one that can enable the full range of the assets’ economic and governance rights, which results in RIAs maintaining those assets directly. Thus, the current reality of the crypto custodial landscape has given rise to distinct legal and operational risks and uncertainty.

What the industry needs is a principles-based approach to solve this critical issue for professional investors who are safeguarding crypto assets on behalf of clients. In developing responses to the SEC’s recent request for information, we have created principles that, if implemented, would extend the goals of the Advisers Act’s Custody Rule — security, periodic disclosure, and independent verification — to the new asset class of tokens.

Crypto assets: How they’re different

A holder’s control of traditional assets means an absence of control by any other person. This is not the case with a crypto asset. More than one entity may have access to the private keys related to a set of crypto assets, and more than one person may be able to transfer those crypto assets regardless of the contractual rights.

Crypto assets also usually come with multiple inherent economic and governance rights that are fundamental to the asset. Traditional debt or equity securities can earn income (such as dividends or interest) “passively” (i.e., without their holders having to transfer the assets or take any further action after acquiring them). In contrast, crypto asset holders may have to take action to unlock certain income streams or governance rights associated with the assets. Depending on the third-party custodian’s capabilities, RIAs may have to temporarily deploy these assets out of custody to unlock those rights. For example, certain crypto assets can earn income from staking or yield farming, or can have voting privileges on governance proposals for protocol or network upgrades. These differences with traditional assets create new challenges for custodying crypto assets.

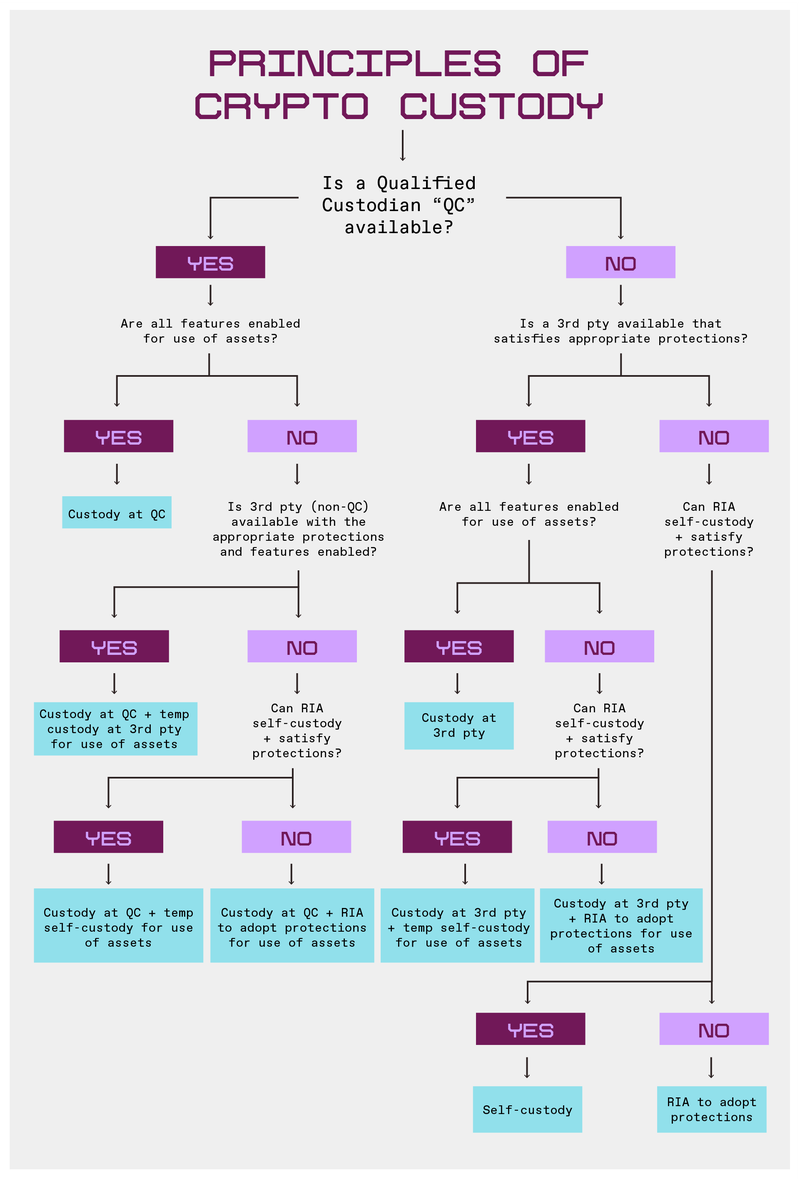

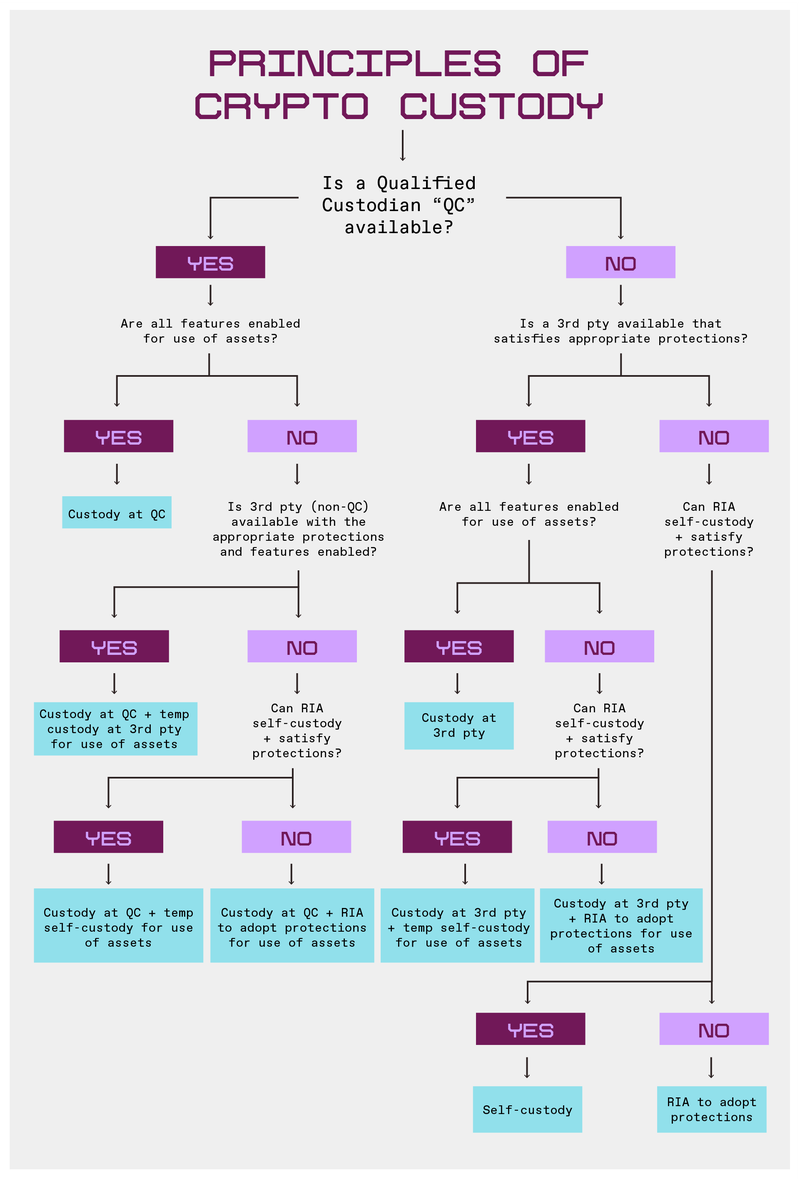

To make tracking when self-custodying is appropriate, we’ve developed this flow chart. The principles follow afterward.

The principles

The principles we present here are intended to demystify custodying for RIAs while preserving their responsibility to safeguard client assets. The current market for qualified custodians (e.g., banks or broker-dealers) specializing in crypto assets is incredibly thin; because of this, our primary focus is on the custodying entity’s ability to meet the substantive protections that we think are necessary to custody crypto assets — and not just the entity’s legal status as a qualified custodian under the Advisers Act.

We also recommend self-custodying as an avenue for RIAs who can meet the substantive protections, when third-party custodial solutions that meet these substantive protections are not available or do not support economic and governance rights.

Our aim is not to expand the scope of the Custody Rule beyond securities. These principles apply to crypto assets that are securities and set forth standards by which RIA fiduciary duties are satisfied for other asset types. RIAs should look to maintain crypto assets that are not securities under similar conditions and should document custodial practices for all assets, including any reason for a material discrepancy between custodial practices for the different types of assets.

Principle 1: Legal status should not determine a crypto custodian’s eligibility

Legal status, and the protections associated with a specific legal status, are important for a custodian’s customers but don’t tell the full story when it comes to custodying crypto assets. For example, federally chartered banks and broker-dealers are subject to custodial regulations that provide significant protections to their customers, but state-chartered trust companies and other third-party custodians can provide similar levels of protections (as we discuss further in Principle 2).

A custodian’s registration should not be the sole determinant of whether it’s eligible to custody crypto assets securities. The Custody Rule’s “qualified custodian” category should be expanded in the crypto context to also include:

- State-chartered trust companies (meaning they would not need to satisfy the criteria in the Advisers Act’s “bank” definition other than being supervised and examined by state or federal authority having supervision over banks.)

- Any entity registered under (proposed) federal crypto market structure legislation.

- Any other entity, regardless of registration status, that can show it meets strict criteria protecting customers.

Principle 2: Crypto custodians should establish appropriate protections

Regardless of the specific technological tools that it uses, a crypto custodian should adopt certain protections around the custody of crypto assets. These include:

- Division of powers: Crypto custodians should not be able to transfer a crypto asset out of custody (e.g., by signing a transaction and/or device-based authentication) without the cooperation of the RIA.

- Segregation: Crypto custodians should not commingle any asset held for an RIA with any assets held for another entity. A registered broker-dealer may, however, use a single omnibus wallet, provided it maintains a current record of ownership of those assets at all times, and promptly discloses the fact of such commingling to the relevant RIAs.

- Provenance of custodial hardware: Crypto custodians should not make use of any custodial hardware or other tools that raise security risks, or concerns about risk of compromise.

- Audit: Crypto custodians should undergo financial controls and technical audits no less than annually. Such audits should include:

- Financial Controls Audits by a PCAOB-registered auditor:

- a Service Organization Control (SOC) 1 audit;

- a SOC 2 audit; and

- the recognition, measurement, and presentation of crypto assets from a holder perspective;

- Technical Audits:

- ISO 27001 certifications;

- a penetration test (“pen test”); and

- tests of disaster recovery procedures and business continuity planning.

- Insurance: Crypto custodians should have adequate insurance coverage (including “umbrella” coverage), or, if unavailable, should establish an adequate reserve, or optionally some combination of the two.

- Disclosure: Crypto custodians must provide annually the RIA with a list of the principal risks associated with its custody of crypto assets and its relevant written supervisory procedures and internal controls that mitigate those risks. Crypto custodians would assess this quarterly and determine whether updates to the disclosure are warranted.

- Location of custody: Crypto custodians should not custody a crypto asset in any location where local law provides that such custodied assets would be part of the bankruptcy estate in the event of the custodian’s insolvency.

Additionally, we suggest that crypto custodians implement protections associated with the following processes at each stage:

- Preparatory: Review and evaluate the crypto asset to be custodied — including the key generation process and transaction signing procedures, whether it is supported by an open-source wallet or software, and the provenance of each piece of hardware and software used in the key management process.

- Key generation: Encryption should be used at all levels of this process, and multiple encrypted keys should be required to generate one or more private keys. Key generation processes should be both “horizontal” (i.e., multiple encryption key holders at the same level), as well as “vertical” (i.e., multiple levels of encryption). Lastly, Quorum requirements should also require the physical presence of authenticators that is secured and monitored against interference.

- Key storage: Never store keys in plaintext, only in encrypted form. Keys must be physically separated by either geographic locations or differing individuals with access. Hardware security modules (or similar) if used to maintain key copies must meet U.S. Federal Information Processing Standard (“FIPS”) security ratings. Rigorous physical isolation and authorization measures should be put in place to ensure airgapping. (See our full response for example measures). And redundancy of at least two levels of encryption should be maintained by the crypto custodian, so that they are able to maintain operations in the event of a natural disaster, power outage, or the destruction of property.

- Key usage: Wallets should require authentication; in other words, they should verify that users are who they say they are, and that only authorized parties can access the wallet’s contents. (See our full response for example forms of authentication). Wallets should use well-established open source cryptography libraries. Another best practice is to avoid the reuse of a key for more than a single purpose. Separate keys should be kept for encryption and signing, for example. This follows the principle of “least privilege” in case of compromise, meaning that access to any asset, information, or operation should be restricted only to the parties or code that absolutely require it for the system to work.

Principle 3: Crypto custody rules should permit RIAs to exercise the economic or governance rights associated with custodied crypto assets

RIAs should be able to exercise an economic or governance right associated with custodied crypto assets, unless instructed otherwise by their client. Under the prior SEC administration, many RIAs took a conservative tact, given the uncertainties about token classification, and custodied all of their crypto assets with qualified custodians (unless none were available). As we previously mentioned, there is a limited market of custodians to select from, and this often resulted in only one qualified custodian willing to support a particular asset.

In these situations the RIA could request that they be able to exercise economic or governance rights, but the crypto custodian could choose, based on its own internal resources or other factors, to not offer these rights. RIAs, in turn, did not feel empowered to select other third-party custodians or self-custody in order to exercise these rights. Examples of these economic and governance rights include staking, yield farming, or voting.

Under this principle we posit that RIAs should select a third-party crypto custodian that complies with the relevant protections that allows for the RIA to exercise economic or governance rights associated with custodied crypto assets. If a third party can’t meet both requirements, an RIA’s transfer of an asset to temporarily self-custody to exercise an economic or governance shouldn’t be considered a transfer out of custody — even if the asset is deployed to any non-custodial protocol or smart contract.

All third-party custodians should make a best effort to offer the ability for RIAs to exercise these rights while the asset remains at the custodian, and shall be permitted, when authorized by the RIA, to take commercially reasonable actions that may be required to exercise any right associated with an asset onchain. This includes the explicit right to delegate any crypto asset to a wallet of the RIA so as to effect any right associated with the asset.

Before taking any crypto asset out of custody in order to exercise a right associated with that asset, an RIA or custodian, as applicable, must first reasonably determine, in writing, whether such rights could be exercised without taking the asset out of custody.

Principle 4: Crypto custody rules should be flexible to permit best execution

RIAs are subject to a duty of best execution with respect to trading assets. To that end, RIAs may transfer an asset to a crypto trading platform to secure best execution for that asset regardless of the status of the asset or custodian, provided the RIA has taken the required steps to assure itself of the resilience and security of the trading venue, or alternatively, that the RIA has transferred the crypto asset to an entity that is regulated under crypto market structure legislation after such legislation is finalized.

Transfers of crypto assets to trading venues should not be considered a withdrawal from custody, provided that the RIA has determined the transfer of the crypto asset to such a venue is advisable to receive best execution. This would require that the RIA has reasonably determined that the venue is suitable for best execution. If the trade cannot be duly executed at the venue, the asset is promptly returned to custody with the crypto custodian.

Principle 5: RIAs should be permitted to self-custody under specified circumstances

While the use of a third-party custodian should remain the primary selection for crypto assets, an RIA should be permitted to self-custody crypto assets if:

- the RIA determines that no third-party custodian that can satisfy the RIA’s required protections is available to take custody of the crypto asset

- the RIA’s own custodial arrangements are at least as protective as that of the third-party custodians that are reasonably available to take custody of the crypto asset

- self-custody is necessary to optimally exercise any economic or governance rights associated with the crypto asset

When an RIA decides to self-custody a crypto asset for one of these reasons, the RIA must confirm annually that the circumstances justifying self-custody remain unaltered, disclose the self-custody to clients, and subject such crypto assets to the Custody Rule audit requirement where the auditors can confirm assets are segregated from other assets of the RIA and are adequately secure.

***

A principles-based approach to crypto custody ensures that RIAs can fulfill their fiduciary duties while adapting to the unique characteristics of crypto assets. By focusing on substantive protections rather than rigid classifications, these principles offer a pragmatic path forward for safeguarding client assets and unlocking asset features. As the regulatory landscape evolves, clear standards rooted in these protections will enable RIAs to responsibly steward crypto investments.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.