Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols

Part IV: Practical Application

This is the fourth part in a series, “Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols”, which establishes a web3 regulatory framework that preserves the benefits of web3 technology and protects the future of the Internet, while reducing the risks of illicit activity and consumer harm. The central tenet of the framework is that businesses should be the focus of regulation, whereas decentralized, autonomous software, should not.

The foundation for the “Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols” framework established in parts one, two and three of this series is regulation agnostic — meaning it is not opinionated about what types of regulation should apply to web3. Instead, the framework provides an approach for evaluating and applying regulations to web3 businesses, including regulations relating to market structure, know-your-customer requirements, privacy or any other type of regulation that currently applies to web2 businesses. The framework only stipulates that a regulation should have a legitimate objective, be appropriately calibrated to the entities and activities it seeks to regulate and the risks it’s intended to address, and remain truly “technology neutral” (not choosing winners among nascent technologies).

In this fourth installment of the series, we demonstrate how the framework could be applied in practice to a hypothetical market structure regulation (i.e. legislation and corresponding regulation governing the trading of digital assets on exchanges). We start by defining the scope of the hypothetical regulation and then explain how different rules and requirements of the regulation might apply to different types of actors and applications in the web3 sector. This analysis shows why the most onerous requirements of the regulation should apply to apps that present the greatest risks to users, whereas those apps that pose the least risk should be subject to less regulation. This risk-weighted approach ensures consumer protection, while also protecting innovation.

While the example regulation we discuss herein focuses on the financial use cases of crypto, the analysis should demonstrate how the “Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols” framework could be used in the future to appropriately tailor a wide array of web3 regulations, including those relating to social media, gig economy, and content creation apps.

Defining the regulation

We begin our analysis by defining the hypothetical regulation to which we will apply the framework and assessing whether such regulation should incorporate the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA).

Market Structure Regulation

Market structure legislation was a key focus of many policymakers and regulators in 2022 (e.g., DCCPA, DCEA, RFIA, etc.) and many continue to believe that regulation of digital asset markets is necessary. We expect there to be renewed efforts to pursue market structure legislation and implementing regulation in 2023 driven by the following policy objectives:

- Protect users from risks, including risks arising from custodial relationships, conflicts of interests, and access to trading illicit assets on unregistered trading platforms;

- Limit trading of illicit assets, including tokenized securities and derivatives; and

- Foster innovation

While decentralized exchanges could potentially be excluded from any market structure legislation and implementing regulation in the short term, it is ultimately unlikely that they will operate outside the bounds of regulation in perpetuity. Such an arrangement would (1) significantly disadvantage centralized exchanges, (2) possibly reintroduce legacy centralization risks in the decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem, and (3) therefore negate the effectiveness of any market structure legislation and implementing regulation. If policy makers scope DeFi into these legislative and subsequent regulatory efforts, it is critical that they appropriately calibrate their objectives and concrete regulatory requirements against the risks that different DeFi entities and activities pose to the ecosystem and their users. This post is an attempt to encourage such an outcome, using a quick example.

Let’s assume that the new market structure law includes a baseline requirement that any trading facility that directly facilitates the trading of a digital asset be subject to registration requirements under one or more new, implementing regulations. The intention is for the law to cover any exchange (centralized or decentralized) where users can directly trade digital assets. The law also includes certain compliance obligations relating to (1) the custody of customer assets, (2) listing rules for the digital assets to be exchanged using the trading facility, (3) record retention requirements for all trading activity, (4) trade processing guidelines, (5) conflicts of interest, (6) governance standards, such as establishing system safeguards for operational and security risks, (7) reporting requirements, (8) financial resources minimums, (9) disclosures of risks relating to use of the exchange and (10) code audits. For our purposes, we’ll call the hypothetical regulation, the ”Regulation”.

Now that we have outlined the principle requirements of the Regulation, it is worth discussing what is not included. First, it is possible that any market structure legislation could include a statutory definition that makes it clear when a digital asset should be deemed a security or a commodity, thereby giving the SEC or CFTC the specific (or joint) authority to promulgate and enforce the Regulation. However, whether a digital asset is a security or a commodity is irrelevant for purposes of the framework, which is a framework for evaluating and applying business-based regulation — not asset-based regulation. A digital asset is not an app, protocol or a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO), it’s an asset. As a result, even though many web3 builders and policymakers alike are hungry for the guardrails this kind of clarification would provide, a clear definition is not actually necessary to apply the “Regulate Web3 Apps, Not Protocols” framework.

Second, any market structure legislation and implementing regulations (including the Regulation) could also include rules relating to other market participants (introducing brokers, broker-dealers, custodians, etc.) and other activities commonly associated with exchanges. Applying regulations designed for these other types of market participants may actually be more appropriate for certain decentralized exchange apps where the nature of the app’s activity is more similar to the activities of such other participants, as compared to a traditional exchange. For example, a decentralized exchange that directs and routes orders may function more like an introducing broker under the Commodities Exchange Act than an ordinary centralized exchange; or it may be better suited for a regulatory framework like the SEC’s “Best Execution” rule than an exchange regime. However, for the sake of simplicity we exclude rules applying to these market participants and treat all apps that directly facilitate trading and exchanging digital assets as exchanges. In any event, even if a proposed regulation were to establish rules relating to these other participants, the analysis below could be applied in the same manner to assess the application of such rules to decentralized exchanges.

Bank Secrecy Act

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) — legislation designed to prevent criminals from using financial institutions to hide or launder money — and its implementing regulations place certain obligations on financial intermediaries, including Customer Due Diligence (CDD) and Customer Identification Program (CIP) requirements (applicable e.g. to banks and broker/dealers) or requirements to verify customers and meet certain reporting obligations relating to customer data and identity verification, commonly referred to as “Know Your Customer” or “KYC” measures (applicable e.g. to money services businesses or “MSBs”). Given the role of exchanges within the broader web3 ecosystem, it is possible that market structure legislation and implementing regulations like the Regulation may subject digital asset exchange activities to requirements under the BSA. These requirements would have little impact on centralized exchanges, who are already regulated as MSBs subject to the BSA; however, applying BSA requirements to apps that provide access to decentralized exchange protocols (and that are not otherwise regulated as banks or MSBs) may not be necessary or beneficial. In practice, these requirements could significantly distort the outcomes of the Regulation and ultimately run counter to the policy objectives behind the Regulation. A closer look at why:

First, the policy objectives underlying the BSA can be accomplished without applying KYC requirements to apps that provide access to decentralized exchanges. Although BSA requirements aid law enforcement in the investigation of illegal conduct, investigators have been able to effectively obtain needed attribution evidence in practice from fiat on and off ramps that are already covered by the BSA, such as centralized exchanges and payment processors (MSBs), and banks. For example, the existing regulatory controls already applicable to money transmitters, including centralized exchanges (e.g., Coinbase and Gemini) and other virtual asset service providers (e.g., Transak and Moonpay), require them to verify the identities of users bringing funds on-chain. This information allows investigators in the private sector, law enforcement, and regulatory communities to collect attribution information of users conducting transactions via these mechanisms, including any transaction executed via a decentralized exchange.

Second, adding new and significant friction to the user experience for apps providing access to decentralized exchange protocols could undermine all three of the policy objectives of the Regulation by pushing users from regulated and legally compliant apps to non-compliant or wholly unregulated apps. As discussed in Part 3, the availability of such unregulated or non-compliant apps is an inevitable consequence of building open and permissionless Internet protocols. As a result, effective regulation needs to be designed to incentivize users to use regulated apps. Requiring all apps to implement KYC measures could have the opposite effect.

The transparent nature of blockchains acts as a very powerful incentive for users to guard their privacy — the accidental (breach or hack) or purposeful disclosure of personally identifiable information (PII) by parties that collect such information could lead to devastating effects, unearthing a user’s entire transaction history and making them a potential target of criminal activity, including identity theft, robbery, and kidnapping. So users are incentivized to provide PII to as few counterparties as possible. The incentive and the opportunity to evade KYC requirements jeopardizes the success of the Regulation and threatens to subject users to greater risks, increase trading of illicit assets, and hinder innovation. Further, the application of BSA requirements to certain apps could in some circumstances raise the possibility of constitutional challenges.

Third, the problem of hindering innovation is compounded by the costs that BSA obligations would impose on startups. In particular, the compliance program and data privacy costs could prove insurmountable for businesses operating nascent for-profit or non-profit apps, thereby disincentivizing entrepreneurs to create and operate them. This would decrease the number of apps available to users and reduce competition, which could introduce centralization risks. For instance, because the for-profit apps that are able to comply would benefit from a lack of competition, such apps would be able to exert more influence on the underlying protocol. Ultimately, this could result in the network effects of the protocol actually accruing to these powerful apps (e.g., as more users sought to use the network, they’d be channeled to the for-profit apps), which would then enable them to extract greater take rates from their users. This dynamic is the antithesis of what blockchain technology is intended to enable (a free, open and decentralized Internet). This anti-innovation environment would encourage entrepreneurs to build elsewhere and could lead to less transparency for U.S. law enforcement.

Fourth, the addition of BSA requirements to the Regulation could undermine the financial inclusion benefits of blockchain technology. For example, decentralized exchanges are a critical linchpin in blockchain-based financial systems, which promise to make financial services, including lending, savings, and insurance, available to a far broader population than current banking systems. KYC requirements would cut short this promise, reducing the potential for underprivileged and disadvantaged populations, including refugee populations, to make use of this technology.

Ultimately, the current law in the U.S. excludes most apps and protocols from the BSA for good reason. As FinCEN explicitly stated in its 2019 guidance, non-custodial, self-executing code or software alone will not trigger BSA obligations because software providers are not money transmitters. FinCEN regulations exempt from the definition of money transmitter those persons providing “the delivery, communication, or network access services used by a money transmitter to support money transmission services.” [31 CFR § 1010.100(ff)(5)(ii)]. This is because suppliers of tools (communications, hardware, or software) are “engaged in trade and not money transmission.”

For the foregoing reasons, we have not included any BSA-related requirements in the Regulation or our analysis of its application.

Applying the regulation

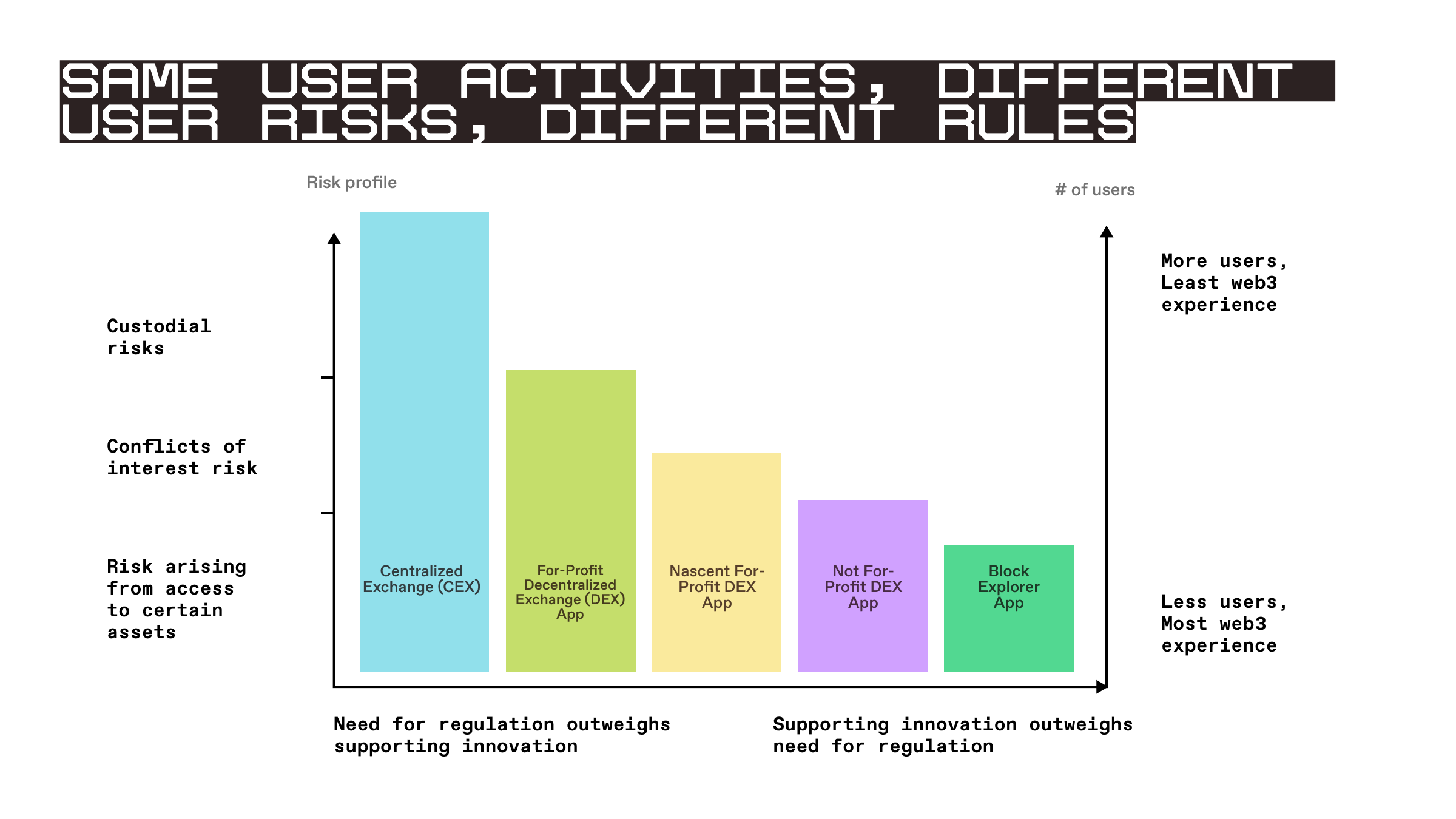

We will now demonstrate how the Regulation (without any BSA-related requirements) might be applied in practice, including to apps with different characteristics, ranging from a centralized exchange all the way to a simple block explorer. We summarize our analysis in the following chart, which maps the relative risks, number of users and need for regulation against the various types of apps analyzed.

We also assess the Regulation’s applicability to decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) and the developers of web3 protocols and apps. Finally, a table tracking the results of our analysis is set forth on Exhibit A.

Centralized exchanges

The registration requirements and ongoing compliance obligations of the Regulation should be applicable to any business operating a trading facility that directly facilitates the trading of digital assets via proprietary software and not via use of a decentralized exchange protocol. In this scenario, the business determines what assets the customers can trade, acts as a trusted intermediary between customers, and acts as a custodian of their funds — and all of these services are all offered for profit. The centralized nature of the exchange introduces legacy risks that the Regulation (and other existing financial regulations) were designed to target. We would therefore expect every requirement of the Regulation to apply to centralized exchanges. However, given that centralized exchanges operate using proprietary software and not via smart contracts deployed to a blockchain, the code audit requirement would provide little benefit — the transactions within the exchange would be fully controlled by the exchange and its execution of trading would be subject to the other requirements of the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchange Protocols

For the reasons we discuss in the first part of this series, the Regulation should not and can not apply directly to any web3 protocols, regardless of whether or not they directly facilitate the trading of digital assets. Simply, protocols could not comply with such a regulation. For example, software could not possibly make the subjective determinations necessary to comply with the listing rules. Even if it could, it would have no way of complying with the conflicting listing rules of every jurisdiction that sought to implement them. There is just no way to apply the Regulation to a protocol without jeopardizing the fundamental principles of protocols we discuss in Part 1 and Part 2. Namely, that protocols must be open source, decentralized, autonomous, standardized, censorship resistant, and permissionless.

However, if web3 protocols are exempt from the Regulation, then the definition of what constitutes a “protocol” matters. If that definition is too broad or permissive, a centralized business could simply evade the Regulation by using smart contracts deployed to a blockchain instead of off-chain proprietary software. If it is too restrictive, no protocol will qualify for exclusion.

The statutory definition of what constitutes a “protocol” should be drawn from the fundamental principles of protocols and balanced with the policy objectives of the Regulation. Exempting protocols that meet these principles would then act as a self-reinforcing incentive for other protocols to adopt the principles and to contribute to an open, free, and credibly neutral Internet.

In particular, protocols which directly facilitate the trading of tokens, such as decentralized exchange protocols (DEXs), to be exempted should have some or all of the following characteristics:

- Open source: Protocols should be open sourced, as this ensures that the network effects of the protocol accrue to its users, not to the owner of the intellectual property that underpins the protocol. Making protocols open source also ensures that they can be forked by competitors, which helps to guard against the protocol gaining popularity and then seeking to extract significant take rates from its users, a practice that has played out time and again with the centralized and proprietary systems of web2.

- Decentralized: Similarly, protocols must not be controlled by any person or concentrated group of related persons as such control would jeopardize the credible neutrality of a protocol. Maintaining credible neutrality is critical to maximizing the network effects of a protocol, as it is a powerful incentive for third-parties to build on top of the protocol and grow the protocol’s network.

- Autonomous: Protocols should generally function as autonomously as possible. Adding human intermediaries to the functioning of software protocols significantly undermines the utility of a protocol and introduces certain risks that such intermediaries could co-opt the protocol to pursue their own interests. In the case of a decentralized exchange protocol, certain limited exceptions should be made to enable pause or suspend trading to mitigate potential risks to users in the event of misuse of the protocol. Further, it may be advantageous to enable adjustments to certain parameters of the protocol, such as the fees that accrue from a particular liquidity pool. However, no such powers should enable the administrators of a protocol to materially alter the primary purpose of the protocol or take control of user funds.

- Standardized: Protocols should seek to make use of standards or to establish standards to the extent possible in order to maximize their potential composability. For example, use of token standards like ERC20 and smart contract standards can ensure protocols are more composable, more secure, and more widely beneficial throughout the ecosystem.

- Censorship Resistant: Protocols must not have the ability to censor individuals or transactions. While the power to censor might appear attractive, such power jeopardizes the credible neutrality and utility of protocols, including by making them susceptible to misuse by bad actors. For instance, a DAO having the power to alter a protocol to censor a user could sufficiently incentivize an individual to seek control of the DAO in order to censor their competitors. One can imagine that if the email protocol SMTP had the power to censor certain providers, that large email service providers like Google might seek to wield their influence to gain control of SMTP, and censor the email services of competitors like Microsoft or Apple. Furthermore, the ability to censor jeopardizes the autonomy of protocols and would likely subject the protocol to globally conflicting regulatory schemes that are not possible to comply with.

- Permissionless: Similarly, protocols must be permissionless in order to maintain their credible neutrality. As with censorship, permissioned protocols can be co-opted for malicious purposes by bad actors, who could seek to block their competitors from using a protocol. Further, the permissionless nature of protocols is critical to maximizing their potential network effects, which is directly correlated with their utility. If developers need permission to build on top of a protocol prior to doing so, they will be more likely to build where such permission is not required. The effect of one jurisdiction imposing permission requirements over protocols would therefore encourage builders to simply develop in jurisdictions where permissionlessness is allowed.

Decentralized exchange apps

In Part 2, we provide a framework for assessing whether a given regulation should apply to an app making use of a protocol. The framework analyzes the purpose of the regulation, evaluates the characteristics and risks of the apps to be regulated (including whether they’re operated for profit and whether their primary purpose is intended to directly facilitate regulated activity), and reviews the constitutional implications of applying the regulation.

In applying the framework to the Regulation’s many rules and requirements, it appears possible to craft all of the rules (other than the custodial rule) in such a way that apps facilitating access to a DEX would be capable of complying. For instance, apps should be able to abide by rules relating to listing, records retention and conflicts of interest. Ultimately, so long as the rules do not require that an app control or dictate the functioning of the underlying DEX protocol, compliance should be theoretically possible. However, per the framework, the custodial rules should not be applied to any non-custodial apps — the risks to be addressed by such custodial rules only arise where apps take custody, so there is no point to apply such rules to apps that do not take custody.

Next, we can consider the policy objectives for applying the Regulation and predict that they will vary depending on the specific characteristics of the app to be regulated (for instance, characteristics relating to how the app functions, whether it is operated for profit, etc.). Such characteristics reveal where asymmetric information risk, centralization risk, or market integrity risk from size and impact over the trading environment could exist. Further, these characteristics indicate where the desire to foster innovation may outweigh the need for regulation, nascent for-profit apps, non-profit apps, and general block explorers.

To demonstrate how the regulation would apply to non-custodial apps making use of decentralized protocols, we can break down into four categories: (i) established for-profit apps, (ii) nascent for-profit apps, (iii) non-profit apps purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets and (iv) non-profit apps not purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets.

Established for-profit apps

The strongest case can be made to apply the Regulation to established businesses operating apps that directly facilitate trading of digital assets via DEXs. First, the policy objectives of the Regulation could be easily undermined if the Regulation was not applied to such apps. Without compliance burdens, these apps could offer lower trading fees, and draw users from centralized exchanges in circumvention of the Regulation. Second, given that these apps are operated for profit, they could introduce certain conflicts of interest risks (relating to the presentation of trading information, collection of fees or routing of trades) similar to the risks of the centralized exchanges. Ultimately, regulation should be technologically neutral — without benefitting one technology (decentralized exchanges) over another (centralized exchanges) — unless they have different risk profiles or there are overriding policy objectives that require a different approach.

One argument in favor of exempting established, for-profit apps would be that the policy objective of fostering innovation outweighs the objectives of protecting users from risks and limiting the trading of illicit assets. We also argue in Part 2 of this series that the case for fostering innovation is bolstered in web3 given that the decentralized protocols of web3 effectively serve as public infrastructure that can be used by anyone (similar to SMTP/email). So, reducing the compliance burden of apps utilizing DEX infrastructure could help incentivize further development of such infrastructure. However, these apps are established (they have a significant number of users and/or high trading volumes), and exempting them from regulation would likely increase the overall weighting of risks described above, which, when combined with the risk of significant regulatory arbitrage, makes it unlikely that the goal of fostering innovation would outweigh the Regulation’s other policy objectives.

Given the foregoing, it is likely that these apps would be subject to the same requirements as centralized exchange unless they do not engage in specific activities (for example, if they do not take custody of user assets). In addition, they should be subject to requirements targeted to their unique risks. For instance, we would expect these apps to be subject to code audit requirements because they make use of smart contracts deployed to programmable blockchains. These audit requirements could also cover the app-smart contract integration to provide assurances that the app provider is not engaging in deceptive activity, such as frontrunning user trades or quoting users slightly higher prices and keeping the difference. While these actions could be seen by regulators on chain, the fact that these crimes leave evidence of wrongdoing may not be sufficient to ensure users are protected from such activity. Alternatively, such activities might be prohibited by the other elements of the Regulation, however it would be more appropriate for such elements to not address the functioning of protocols. As a result, the code audit may be the more appropriate requirement to apply.

Outcome: Subject to registration requirements of the Regulation, excluding custody requirements but including code audit requirements.

Nascent for-profit apps

For nascent or small for-profit apps, the foregoing balancing of innovation vs. competitiveness policy objectives may be more likely to come out in favor of fostering innovation. For instance, where apps fall below thresholds relating to user numbers, trading volumes, or trading commissions, the quantum of risk to users and the amount of illicit trading would be significantly reduced. Meanwhile, the cost of applying burdensome regulatory barriers to entry or regulatory economies of scale to nascent or small for-profit apps is significant and could be detrimental to web3 innovation, particularly at this early stage in the technology’s development. If applied, the Regulation could effectively act as a moat, stifling competition. As a result, the policy objective of fostering innovation may outweigh the risks the Regulation is intended to address in these cases. A “regulatory sandbox” or “safe harbor” exempting such apps from the requirements of the Regulation may be appropriate.

However, even when regulators deem nascent, for-profit apps to be exempt, consumer protection regulations like disclosure requirements could help inform users of the risks of using a DEX. Code audit requirements could also protect an app’s users against smart contract failures of the DEX while ensuring the app functions as advertised. As a result, it may be prudent to condition the exemption of these apps from registration on their compliance with upfront risk disclosure and code audit requirements, or ongoing requirements if the risk profile or code changes. This balance would help protect customers while not overly burdening new entrants and stifling competition and innovation.

Outcome: Likely exempt from the registration requirements of the Regulation, but subject to compliance with upfront or on-going disclosure and code audit requirements.

Not-for-profit apps, purpose-built to directly facilitate trading digital assets

Where web3 apps are not operated by a business for profit, the relative weighting of the policy objectives of the Regulation should become even more favorable to fostering innovation. Not-for-profit apps are unlikely to present many of the risks of for-profit apps, particularly with respect to conflicts of interest. In addition, if no one is profiting, there are few or no incentives creating conflicts of interest or encouraging operators to facilitate illicit trading.

However, a minimum level of protection could nevertheless be achieved by continuing to apply the disclosure and code audit requirements. These apps are either developed with the specific purpose of providing users with access to a DEX or designed to direct users to a specific DEX, so it follows that they should be responsible for providing users with upfront risk disclosure and code audit requirements, or ongoing requirements if the risk profile or code changes. Both requirements can be easily satisfied, meaning they are unlikely to hinder innovation, yet they offer meaningful protection to users.

Outcome: Likely exempt from the registration requirements of the Regulation, but subject to compliance with upfront or ongoing disclosure and code audit requirements.

Not-for-profit apps, not purpose-built to directly facilitate trading of digital assets

If an app is simply a block explorer or other general purpose tool for interacting with blockchains and smart contract protocols, it should not be subject to the Regulation and its requirements. Applying the Regulation in this scenario would be akin to regulating underlying protocols directly and would therefore stifle innovation. The line between regulating software vs. businesses needs to be protected, and is most appropriate here. Even the disclosure and code audit requirements discussed above should not apply to such general purpose apps, many of which are tools capable of interacting with every protocol in existence on a given blockchain. As a result, code audit and disclosure requirements would be impractical, if not impossible, to comply with.

Outcome: Excluded from all requirements of the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchange DAOs

If the DAO maintaining and administering the affairs of a DEX were able to profit from any transaction executed through the DEX, then the DAO would effectively be incentivized to facilitate and encourage trading to take place through unregistered exchanges offering the most permissive and least regulated trading environments, including with respect to the listing of assets. This would significantly undermine the policy objectives of the Regulation relating to protecting users and curtailing illicit trading. As a result, in order to ensure the policy objectives of the Regulation can be achieved, the DAO of any DEX may need to be subject to certain additional safeguards (including disallowing the DAO from receiving commissions on trades and other transactions initiated by noncompliant apps). For the Regulation, such safeguards could establish the following restrictions:

The decentralized organization tasked with developing, operating, administering, or maintaining any DEX shall be required to (i) utilize mechanisms reasonably designed to prevent the collection and distribution of fees and/or commissions, directly or indirectly, to the DAO from transactions initiated through applications facilitating the trading of digital assets that are not registered pursuant to and in compliance with the Regulation and (ii) forego activities whose primary purpose is to facilitate or encourage the execution of transactions through applications directly facilitating the trading of digital assets that are not registered pursuant to and in compliance with the Regulation.

These safeguards would ensure that the DAO could not profit off of transactions initiated from applications that were unregistered, thereby incentivizing the DAO to encourage and facilitate trading through registered apps and removing any incentives the DAO may have to encourage and facilitate the use of such unregistered applications in circumvention of the Regulation.

Decentralized Exchange Developers

There should be no direct regulation of persons or businesses that develop or publish software. Such restrictions would come with significant costs and provide no benefits. The excessive encroachments on personal freedoms necessary to successfully curtail the development and publication of open source software would be challenged and defeated on constitutional grounds. However, the proposal and approval of such restrictions in the intervening period before their ultimate legal defeat would have a lasting and irreparable effect on the legacy of the United States and its role in shaping our collective digital futures.

Conclusion

The effective regulation of web3 is a significant undertaking that is complicated by the presence of decentralized and autonomous global software. However, rather than regulate this software, we must focus on tailoring regulations like the Regulation to the businesses operating apps on top of it. As demonstrated above, that process must begin with the establishment of clear policy objectives and include a dynamic weighting of such objectives based on the characteristics of the apps to be regulated. In addition, it does not require the elimination of the possibility that web3 technology may be used for illicit activity, but it does require measures designed to reduce the risk of and disincentivize illicit activity. Further, safeguards are necessary to ensure DAOs are not utilized as loopholes, but in no case should developers themselves be regulated.

Ultimately, the proper regulation of web3 technology can unleash its potential and result in the addition of many new forms of native functionality to the internet. This new layer of the web will act as public infrastructure upon which millions of new internet businesses will be built.

Exhibit A: Summary of Regulatory Compliance Requirements

| CEX | Protocol | Established For-Profit App | Nascent For-Profit App | Purpose-Built Not-For-Profit | Not Purpose-Built, Not-For-Profit | DAO | Developers | |

| Custody | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Listing | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Records | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Trade Processing | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Conflicts of Interest | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Governance Standards | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Reporting Requirements | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Retention of Financial Resources | Yes | No | Yes | Depends | Depends | No | No | No |

| Disclosure Requirements | NA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Code Audits | NA | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Value Accretion Safeguard | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA |

| Semi-Autonomous Safeguard | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Yes | NA |

* The application of these rules would be dependent on the relative weighting of policy objectives behind the Regulation.