web3 has created a new laboratory for democratic governance that interweaves civic and corporate governance traditions in a way previously impossible. Public and private incentives are entwined. Projects are open source and for-profit. Public goods coexist with private initiatives. Governance is continuous, participation is radically open, and execution is rapid.

This new laboratory for governance is defined by different classes of actors, erasing previous distinctions because the customers are the owners. As a result, a new form of digital participation is emerging, featuring widespread experimentation and fast cycles of iteration. It’s democracy at lightspeed.

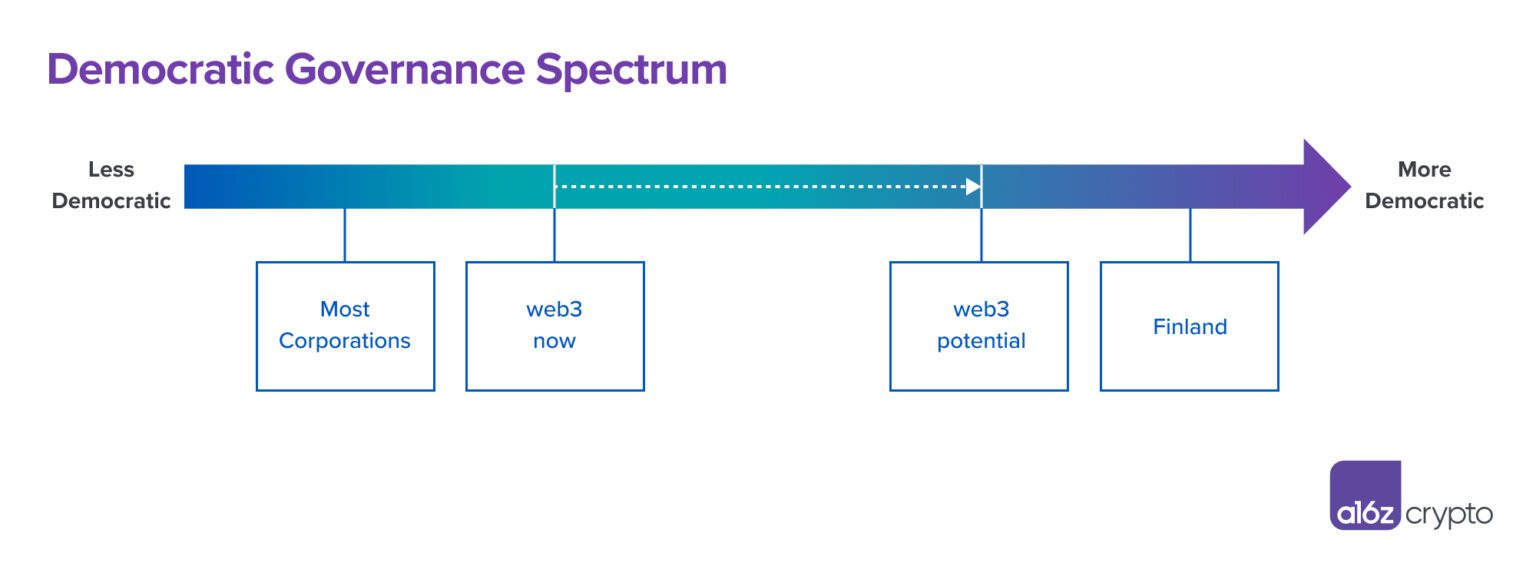

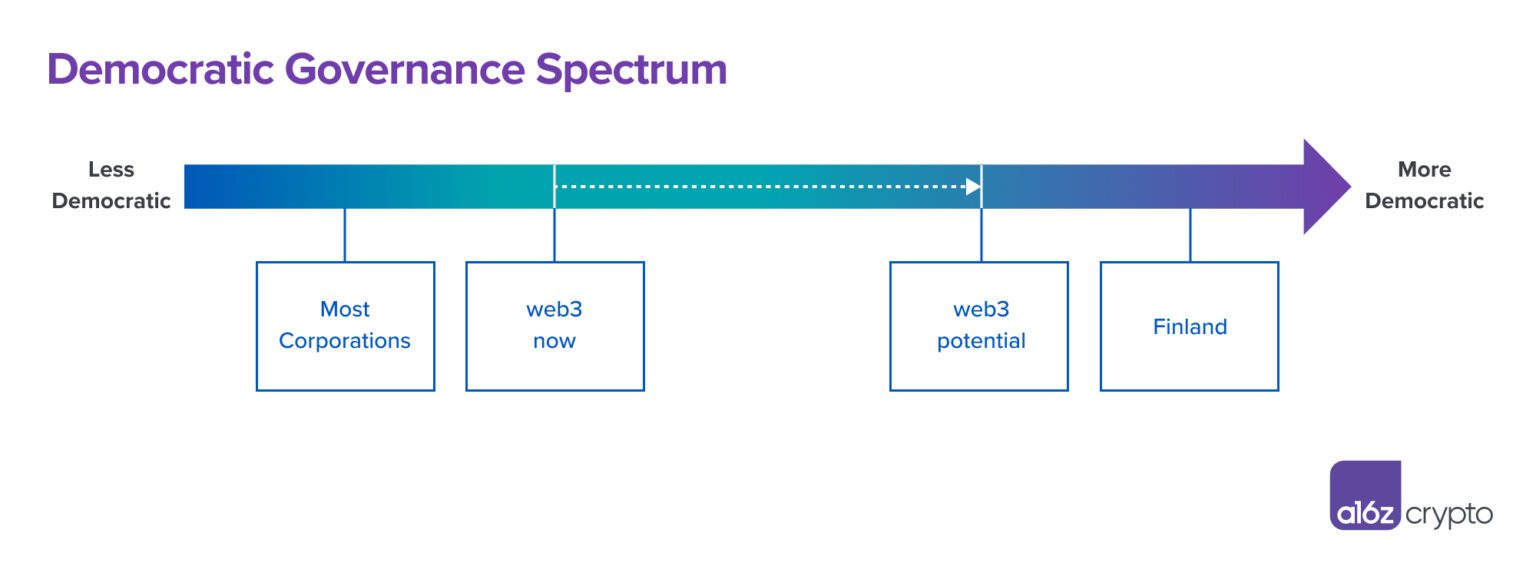

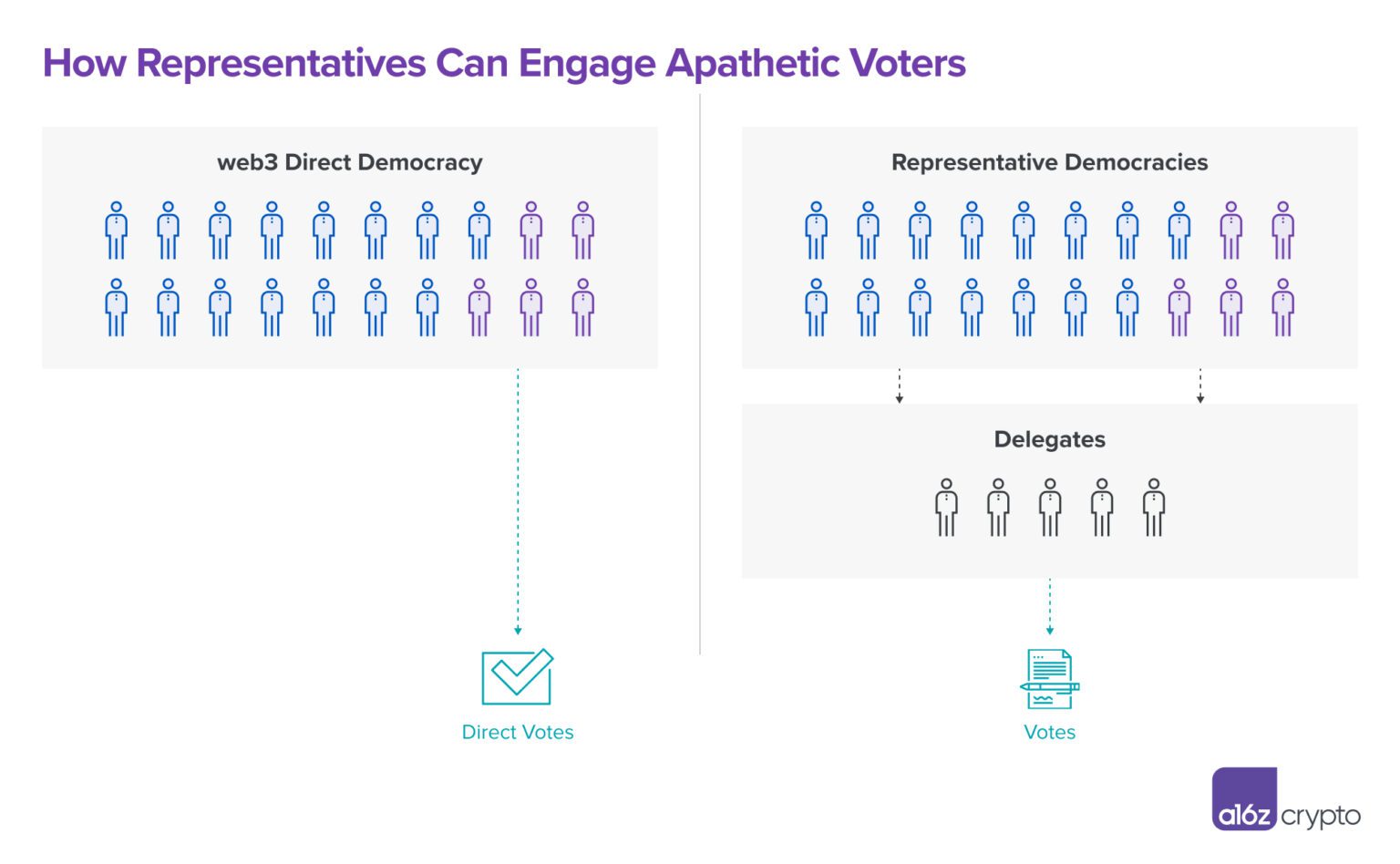

To date, though, web3 governance has overly relied on direct democracy, leading to low participation and concerns about weak oversight, interest-group capture, and group decision-making. There’s room for borrowing best practices from the history of governance systems.

Because while web3 is new, governance isn’t. These are the same governance challenges societies and organizations have experienced for millennia – spanning from the cradles of the Athenian Ecclesia, where citizens came together to make collective policy decisions, to the rise of the Dutch East India Company, which could distribute risk and aggregate capital at scale. They did this by adding a layer of legal insulation between shareholders and creditors, heralding a new era of organizational design and privatized governance through the rise of the corporation.

Tensions between competing imperatives—empowering experts versus encouraging broad participation, creating open systems versus capture of those systems by non-aligned actors—have always loomed large. But web3 has the chance to learn from this history, applying hard-learned lessons from democracy and corporate governance to build more effective political systems by:

- Moving from direct democracy to representative democracy in order to mitigate problems of low voter participation and low information that create risks of interest-group capture,

- Building more explicit governance institutions that go beyond simple token-based voting in order to represent all stakeholders, and

- Empowering delegates to provide oversight and auditing functions to build trust among all actors.

This could result in more mature governance systems that preserve the power of the community to self-govern, while also mitigating the interrelated challenges of voter participation, information availability, and interest-group capture through rapid experiments and innovation in governance structures.

Drawing on our expertise in political science and political economy research, and our experience observing and actively participating in web3 governance in longstanding DAOs, we explore the key challenges to decentralized governance and offer a path forward to build the mature decentralized governance systems of the future.

Understanding the limits of direct democracy

Today, web3 governance heavily relies on a referendum-based, direct democracy approach to decision-making. Ancient Athenian democracy was similar, relying on certain members of the public to discuss and decide many issues through consensus.

Direct democracy creates issues of scope (what should the community be able to vote on?), depth (does the community have the relevant expertise on these issues?), and efficiency (what decisions could be delegated to others?). It’s hard for citizens to study every issue and show up to debate and vote—and it’s arguably irrational. If there are many other voters, your own vote is unlikely to matter, so why bother learning the issues or voting at all? This is sometimes called “the paradox of voting”, and it’s been explored by democratic theorists at least as far back as the 1790s, when Nicolas de Condorcet published his “Theory of Voting.”

Perversely, by asking voters to do more, direct democracy models can become less democratic. This is because it can lead to low rates of participation and insufficient public analysis of core issues, which in turn allows strategic actors to influence policy for their own gain. As Mancur Olson, the public choice theorist, famously argued, concentrated interests can push policies that benefit themselves at the expense of the voters at large. Because the costs of the policies pushed by these concentrated interests are spread out across voters as a whole, it’s hard to coordinate to stop them.

We’ve already seen this problem play out in some decentralized organizations, where small groups of token holders have pushed proposals to their exclusive benefit, and the issue is likely to become more severe as the stakes become higher.

The Federalist Papers and web3: How representative democracy can improve decentralized governance

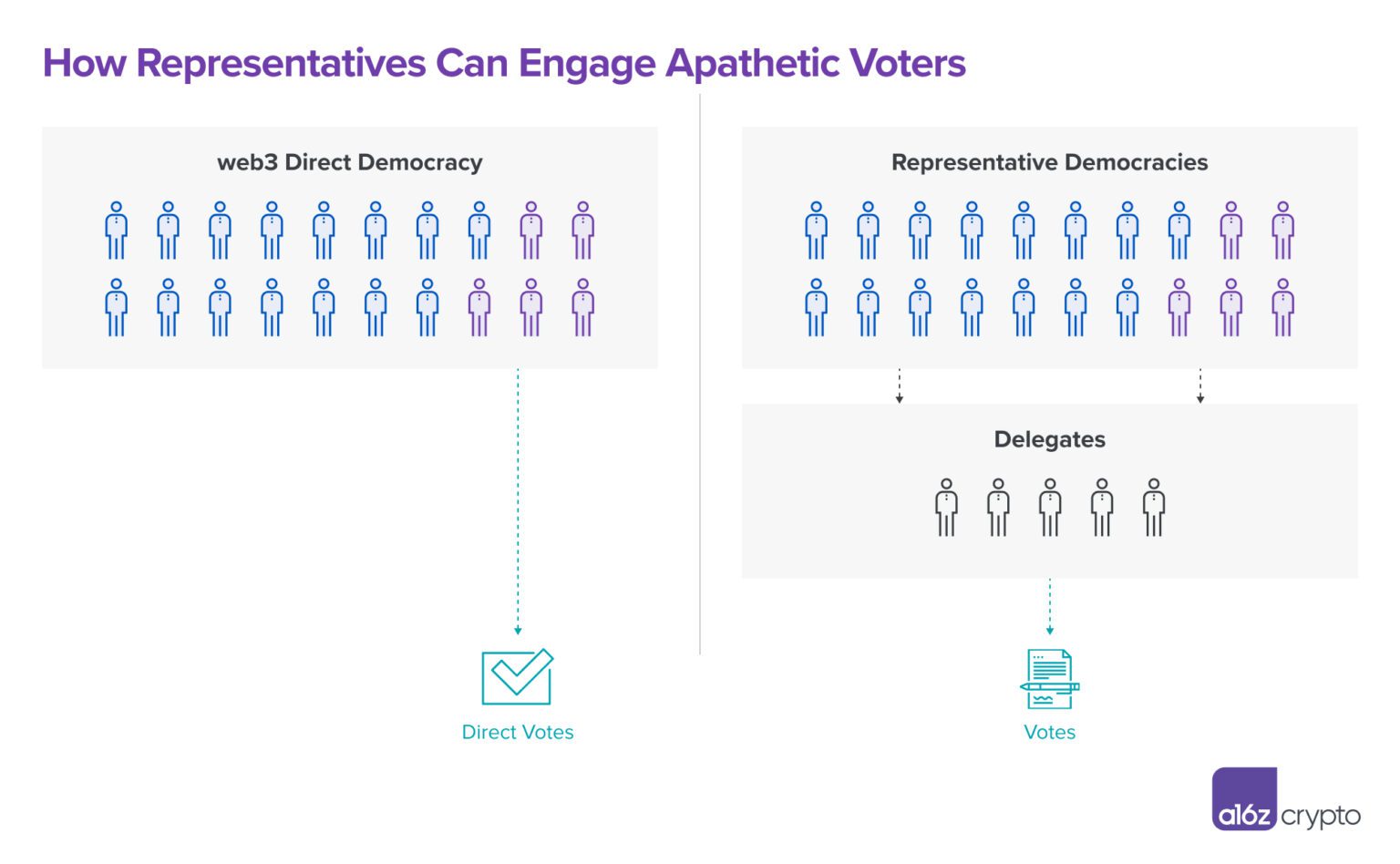

In an attempt to solve these problems, real-world governance models evolved toward representative democracy. Representation helps to mitigate the voter apathy and information problem. Instead of having to constantly study issues and make decisions, voters need only to study a finite set of candidates and periodically decide which ones to elect.

Some argue that representative democracy is less democratic than direct democracy, but this is a fallacy: by asking less of voters, representative democracy can actually empower them more, channeling and focusing their activity in a bid to encourage participation and prevent concentrated interest groups from capturing the system.

The same logic holds for corporate governance. Apple doesn’t rely on its shareholders to vote on the technical framework for the next generation iPhone. Amazon doesn’t openly solicit shareholder feedback for each step of its fulfillment center growth plans. Instead, shareholders are asked to make a small set of periodic decisions, such as electing a board of directors who are tasked with serving in an oversight role on behalf of shareholders.

This is consistent with the Madisonian view of republican democracy. As James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 14, “In a democracy, the people meet and exercise the government in person; in a republic, they assemble and administer it by their representatives and agents. A democracy, consequently, will be confined to a small spot. A republic may be extended over a large region.”

In our view, philosophical parallels to Madison’s logic exist in web3 today. The primary impediment is no longer physical travel, but system complexity. We expect to see more sophisticated and widespread forms of representation within web3 governance continue to develop as an antidote to rising complexity. From a first principles perspective, web3 communities need to decide on the political system design and social contract between actors in the ecosystem before applying the specific tools to implement them.

While web3 governance should be different from older archetypes, it can also incorporate well-designed representative elements from traditional frameworks to build more inclusive and efficient organizations. Examples include explicitly defining the roles of internal units, requiring certain expertise from representatives making decisions regarding those units, and ultimately leaving strategic capital allocation decisions to all voters as a check on the organization itself. In turn, these changes can foster political scalability, or the ability for groups to effectively organize in a representative manner even when they grow exponentially, without sacrificing organizational decisiveness, agility, or inclusion.

Balancing competing interests

Delegation is but a first step among many. An effective decentralized governance system finds ways to appropriately represent the preferences and priorities of many relevant stakeholders, including token holders, reflecting the unique blend of public and private governance models inherent to web3. And it needs to do this while also leveraging sufficient expertise to make good decisions regarding detailed issues.

Every constitution reflects a different balance between these factors. A constitution—whether formally written down or only informally defined—identifies the core stakeholders in a society or organization and constructs institutions that channel the views of these stakeholders in different ways, giving priority to some over others, drawing boundaries between different actors, and delineating flexibility for unanticipated future conditions.

As web3 organizations experiment with different political structures, they can zero in on effective constitutional arrangements that balance accountability and efficiency of decision-making.

Spinning up the accountability flywheel

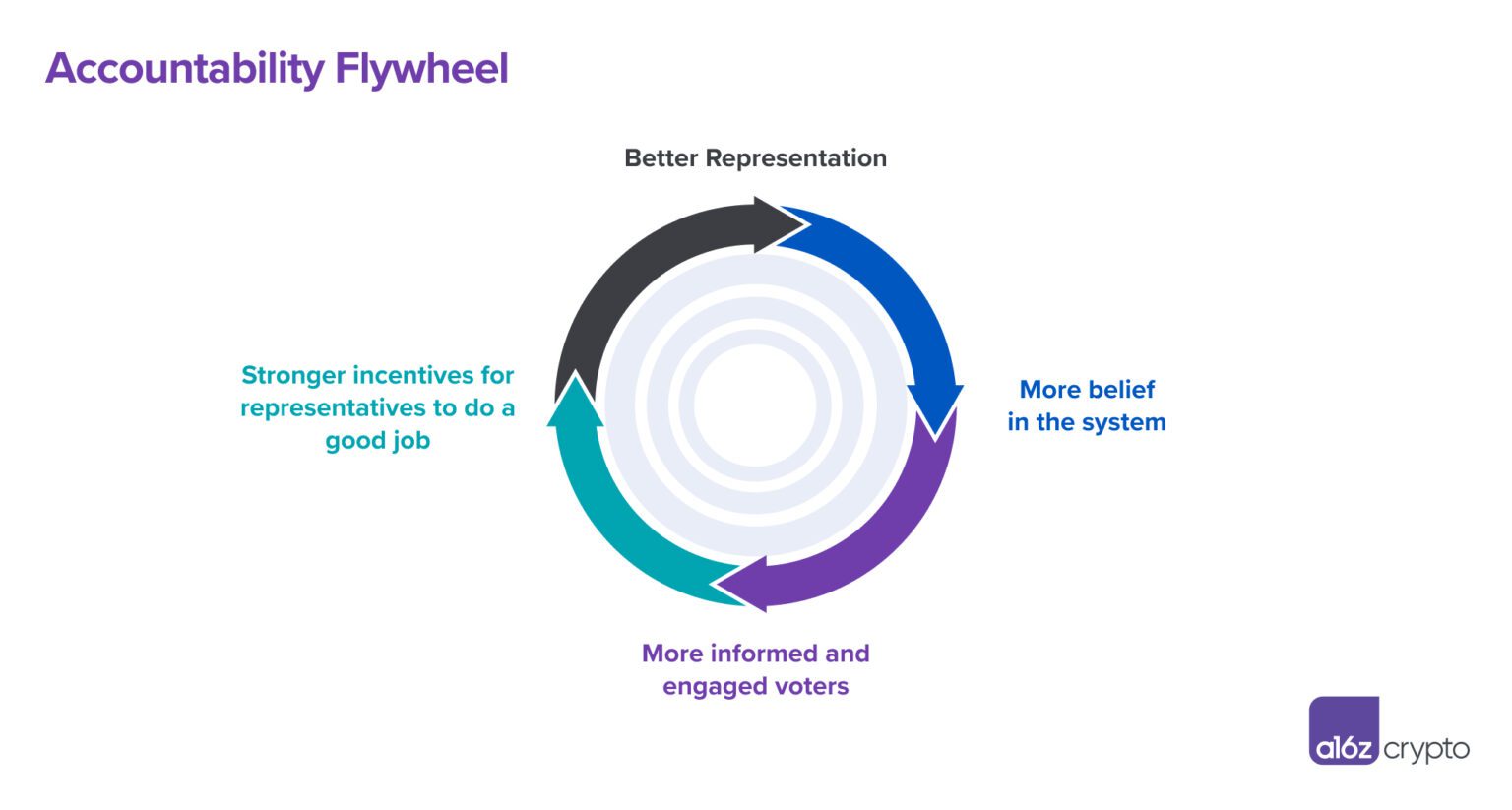

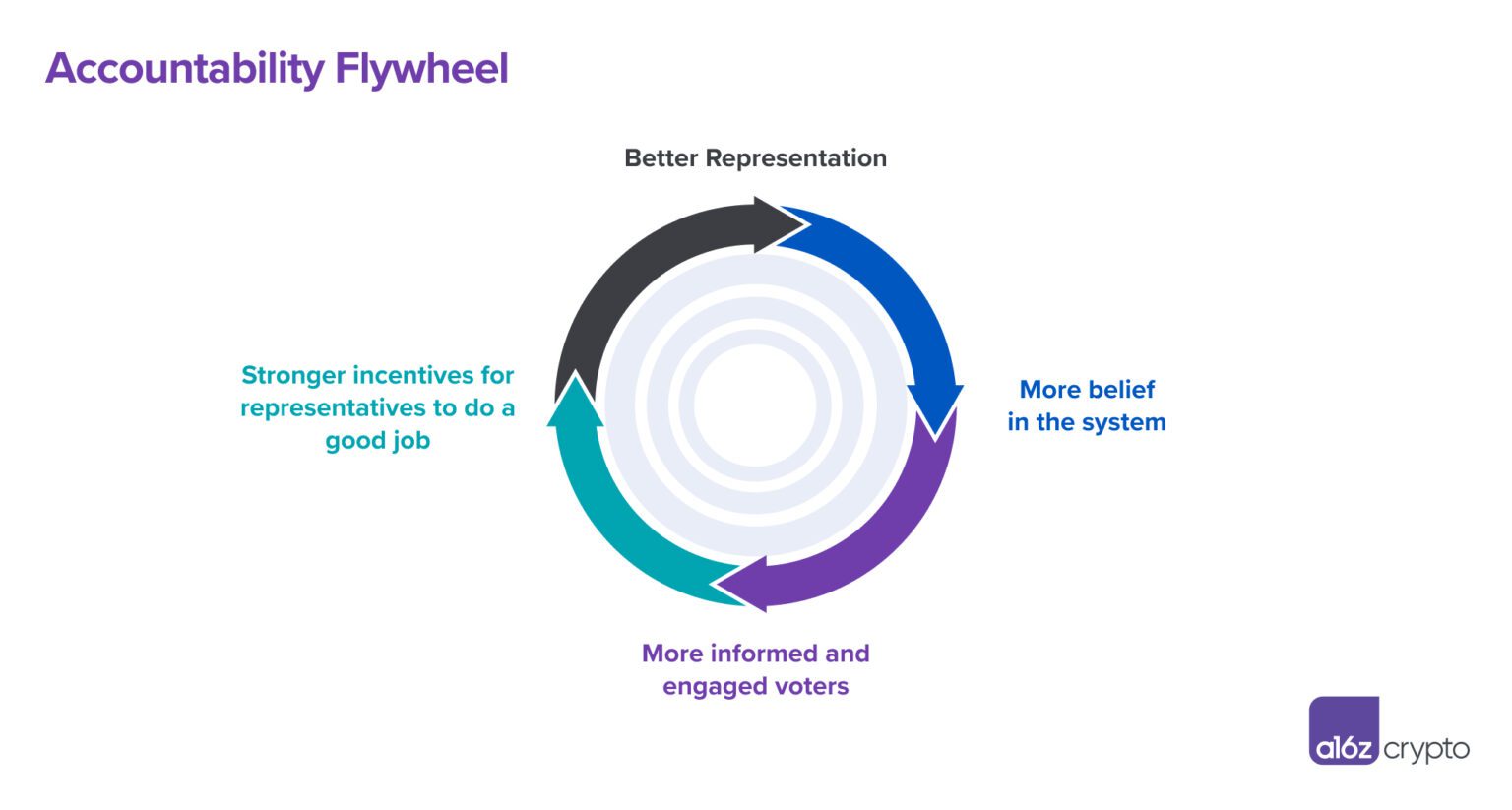

Representative democracy only works well when it solves its principal-agent problem: representatives must want to win reelection, and voters must be armed with the information necessary to figure out whether their representatives deserve reelection or not. In the same way, in corporate governance members of the board of directors must act in the long-term interests of the corporation or risk possible removal by shareholders, even if such removals do not commonly occur.

web3 makes us think about this problem differently. For one, right now there is no board of directors. Many actors are pseudonymous, the threshold for engagement and disengagement from an organization is low, and representation is facilitated in a highly liquid manner, often through tokens.

Yet generally speaking, the more informed and attentive voters are, the stronger the incentives are for representatives to do a good job. And when representatives do a better job, stakeholders believe in the system and are more willing to put the time and effort in to pay attention—further enhancing the incentives for representatives to do a good job. In this way, if successful, the system becomes self-reinforcing: good governance begets more good governance.

We call this the accountability flywheel. And web3 has a powerful tool to facilitate it—the token. Tokens can be used as a new vehicle for distributing economic, social, and political rights to stakeholders within an ecosystem. Much like how start-ups can incentivize employees with ownership, tokens can be used to incentivize contributors and users to continue building value on a network.

But simply enabling token delegation is not nearly sufficient to spark the flywheel. There are two broad categories of changes that can help:

- Encourage competent and engaged delegates by compensating them appropriately, defining their role, and perhaps guaranteeing them a certain period of time in office.

- Tokens can play a key role maintaining long-term incentive alignment through vesting periods, similar to performance-based stock options for corporate board members.

- Keep delegates accountable to token holders through objective analysis of their performance.

- Transparency is insufficient for accountability. Token holders, like voters, need well-organized information. Succinct data on voting activity and recommendations from specific experts in defined areas of responsibility, such as credit underwriting, can be helpful for ensuring accountability.

- This could include organization-specific audit and reporting functions similar to the role the media plays in free and fair elections in democracies. It could also include publicly funded media functions that exist across related organizations and that receive funding from L1 blockchains and associated foundations.

Who else deserves a microphone, and how loud should it be?

Delegates who represent token holders are one important part of the system, but they are not the only one. As Vitalik Buterin has argued in his 2016 piece on decentralized governance, there are many important voices beyond large token holders, and pure token-based voting may not incorporate them. The corporate governance aspects of web3 political design (one token, one vote) make this a difficult problem to solve because token weights are generally skewed toward founding teams and institutional investors. Other stakeholders might include people who contribute actively to a protocol despite holding few or no tokens, users of the protocol who may not hold tokens, and the full-time workforce of the protocol.

On the other hand, non-token holders don’t have direct skin in the game. This can lead to incentive misalignment as they don’t bear the economic consequences of their actions, especially in open governance systems that allow active participation through debate or proposals from non-token holders. Traditionally, these actors (often customers) have influenced an organization’s direction through indirect social or economic influence—public reviews, temporarily trying a competitor, or ultimately no longer being a customer. But web3’s openness charts an avenue for participation for anyone who isn’t a “shareholder,” creating a double-edged sword.

Inclusion is a standard problem in corporate governance. We have seen this dynamic at play recently with activist proposals from minority shareholders, often referred to as “stakeholder capitalism.” Debates over who count as relevant stakeholders, and how the views of non-shareholders should be reflected—including society at large, employees, and customers—have become increasingly important. Engine No. 1, an activist investor, allegedly spent only $12.5M to have three of its four nominated directors elected to the board of Exxon, a company worth over $400B, over concerns with climate change and corporate strategy.

Inclusion is also a classic issue in democratic governance. Governments the world over and across history have tinkered—sometimes for good, other times for evil—with who is allowed to vote and how those votes translate into political power. Often, this constitutional engineering has focused on physical geography, assigning each geographical area a certain share of political power through districts or constituencies.

Many societies have experimented with ways to guarantee the representation of certain groups, too. This social geography might include gender quotas for candidates, reserved political positions for members of certain castes, or “majority-minority” districts in the U.S. Web3 governance can experiment along similar lines, and some have already started. This can include:

- Distributing governance tokens directly to relevant groups.

- Current example: retroactive airdrops to people who have meaningfully contributed to a protocol.

- Creating a separate governance function for a constituency.

- Current example: Optimism’s “Citizens’ House,” which is a voting chamber composed of community contributors, each given one vote through a non-transferrable token. The Citizens’ House allocates funding for public goods projects.

- Reserving some representative slots for specific groups, such as full-time contributors, active forum members, or the user base.

- Current example: none yet, but this is a logical next step that can expand the delegate system beyond pure token voting, perhaps even incorporating input from full-time contributors.

- Giving power to non-token holders through other means

- Current example: Lido’s governance proposal to give dual governance powers to LDO holders and stETH holders, who would have veto rights over certain types of proposals.

Navigating the balance between leveraging expertise and preserving broad representation

Representation is an important ideal, but realistic governance also means making informed decisions on complex issues. Such issues are especially widespread in web3 because of its technical nature.

Unfortunately, creating a representative system is often in tension with creating an expert one. Democracy has faced this challenge from its very earliest history. Indeed, Socrates’s distaste for democracy stemmed from the belief that governing required expertise and should not be left to the unexpert. He drew an analogy between the state and a ship – the “ship of state” – arguing that just as we would not fire the navigator on a ship and let the unexpert crew navigate, we should not leave the governance of a society to the supposedly unexpert members of the community. Yet the opposite extreme—autocratic rule by self-appointed experts—is clearly incompatible with free societies.

In general, democracies’ preferred approach is indirect accountability. People with relevant skills and expertise work as full-time employees of the state, not having to seek election themselves, but being subject to sanction or firing by officials who are in turn elected. This is thought to have two benefits. First, to recruit workers who may lack the interest or “charisma” to be elected politicians but who have crucial skills and knowledge; and second, to create at least one degree of separation between these employees’ work and the intense and sometimes myopic pressures of the electorate.

Corporate governance works similarly. The directors of the board are, loosely, akin to elected delegates of the shareholders at large. They in turn oversee the executives who run the company. The executives do not themselves have to run for election, but at the same time, they are accountable to shareholders indirectly. The board of directors is not expected to be fully expert in the abstruse day-to-day decisions that the executives make for the firm, but it is expected to evaluate whether the executives are doing a good job overall.

A useful model for web3: Indirect accountability

Today, web3-native organizations have scarcely leveraged indirect accountability. They should. There are two general approaches they could try:

- Give representatives, whether appointed or popularly elected, formal oversight powers.

- This would be perhaps closest to the corporate governance model, although in web3 the delegates could have more powers than corporate boards do, and token holders could be asked to undertake a wider variety of direct votes where appropriate.

- As commonly outlined in both corporate charters and constitutional studies, a critical oversight power is the “power of the purse.” In the case of web3, this would mean the power to oversee community treasuries, which implies the ability to fund or defund certain positions, projects, and groups within the organization.

- Create an executive committee that either (a) involves delegates with the most tokens delegated or (b) full-time employees hired by the delegates. The executive committee would be responsible for overseeing the workforce and articulating a unifying vision for the organization.

- This would be closer to a parliamentary model, or a “council-manager” style municipal government in the United States.

It is still important to note that in designing any governance system, actors should not create information asymmetries that might necessitate the application of securities laws to the underlying tokens in order to protect holders and users. In particular, communities need to ensure that governance designs don’t result in the value of the underlying token being substantially dependent on the “managerial efforts” of such representatives, as in such cases, the tokens could be deemed to be securities by the SEC. [For more on principles and models for decentralization, especially for builders, please see this piece (including links to a more detailed paper) by Miles Jennings; and for more on legal frameworks for DAOs specifically, see this series.]

Trust, but verify

With a system that balances representation and expertise, oversight becomes vital. The token holders-at-large need to trust that the permanent workforce of the decentralized organization—the group of experts—is acting in their best interests, in the same manner that voters and politicians must trust the bureaucracy, and shareholders must trust the executives and employees of the firm. This trust can never be complete, and it does not appear magically. Instead, it exists in a delicate equilibrium that is built on a foundation of credible oversight.

The legislature is charged with overseeing the bureaucracy, and in most political systems has broad powers to investigate its activities; in much the same way, in corporate governance, the board of directors has the power to audit the firm and to investigate its actions.

Right now, where they exist in web3, delegates largely focus on seeing and voting on proposals. In the future, it will be natural for them or some representative committee to provide oversight of the permanent workforce on behalf of token holders. There are several potential elements to help make this work well:

- Formally charge certain representatives with overseeing the workforce.

- Provide resources like professional staff to help delegates audit the workforce, investigating budgets and evaluating performance.

- Reserve a small number of critical decisions for token holder referendums. This could include, for example, a once-a-year vote on the overall budget plan. By making this vote infrequent and extremely important, it may be possible to sustain sufficient, informed participation.

***

web3 is new, but governance isn’t. We’ve been tinkering for centuries. Building on what we can learn from traditional governance, web3 organizations can harness the power of representation, balance expertise and representativeness, and develop mechanisms to ensure oversight and trust.

But web3 organizations shouldn’t stop there. They can go much farther, and faster, than traditional forms of governance. In the physical world, experiments in democracy are slow. It could take decades or even centuries to figure out if one form of constitution worked better than another. In web3, protocols run continuous experiments to develop and test new forms of representation, creating the potential for faster governance cycles.

Further, the commitment power of blockchains becomes especially powerful when combined with the tools of democracy, because democracy provides the promise that property rights and the system around them will persist into the future, in code. Together, they provide the chance to create well-governed platforms that can enter into credible and enduring commitments with counterparties, unleashing new forms of economic activity and growth.

These properties make web3 an invaluable laboratory for democratic governance—the topic we will address in the sequel to this essay, where we lay out how web3 applications can bring effective governance to the social media and commerce platforms of the future.

Andrew Hall is a Professor of Political Economy in the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University (as of July 1) and a Professor of Political Science. He is an advisor to tech companies, startups, and blockchain protocols on issues at the intersection of technology, governance, and society.

Porter Smith is a Deal Partner on a16z’s crypto team.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.