On January 1st each year – New Year’s Day, but also “Public Domain Day” – thousands of creative works automatically enter the public domain for the first time. This means the original creator or copyright holder loses their exclusive rights (e.g., for reproduction, adaptation, or publication), and the work in question becomes free for use by all. It happens with movies, poems, music, artworks, books – where creative protections typically last until 70 years after the life of the author – and even happens with source code in some cases.

Opening creative works to the public domain also opens the door to all manner of new uses. Earlier this year, an estimated 400,000 sound recordings from before 1923, and the well-known Winnie-the-Pooh, became public. (That’s Winnie-the-Pooh in hyphenated form – not the newer, shirt-wearing version from 1961 that’s still owned by Disney.) With most of the characters from A.A. Milne’s 1926 Winnie-the-Pooh book now public, we’re starting to see creative adaptations and expressions Milne likely never expected or intended. Indeed, the old hyphenated version of the honey-loving bear is already being adapted for a horror movie: “Winnie-the-Pooh: Blood and Honey”… with Pooh and Piglet as the villains.

Counterintuitively relative to many classic intellectual property (IP) strategies, experimentation and recombination can sometimes grow the value of IP. This is a core dynamic of open source movements, which explicitly allow the public to build upon (or fork and duplicate) existing technology. A large part of what makes Android, Linux, and other successful open source software projects so competitive is their embrace of such permissionless innovation. Crypto’s success at attracting public development is similarly due to its general endorsement of open source, and “remix culture,” which is especially true for some NFT communities.

Seizing the memes of production

Strategies for building brands, communities, and content through IP vary greatly across NFT projects. Some maintain more or less standard IP protections; others give just NFT owners rights to innovate upon the associated intellectual property; while still others have gone even further, choosing to completely remove copyright and other IP protections.

By issuing digital works through the “Creative Commons Zero” (“cc0”) license – a rights-waiving tool released by the Creative Commons nonprofit organization in 2009 – creators can knowingly opt for “no rights reserved.” This option allows anyone to make derivative works and profit from those efforts without fear of legal consequences. [There’s still a lot of confusion around copyrights as applied to NFTs, so nothing stated here should be considered legal, financial, tax, or investment advice – but check out this article for an overview of copyright vulnerabilities with NFTs, and how creators can take steps to ensure owners’ rights. The focus of this piece, however, is on just cc0.]

The use of cc0 for NFTs was popularized by the Nouns project, launched in summer of 2021. Many others soon followed, for example: A Common Place, Anonymice, Blitmap, Chain Runners, Cryptoadz, CryptoTeddies, Goblintown, Gradis, Loot, mfers, Mirakai, Shields, and Terrarium Club are all cc0 projects – and many, many, many derivatives have been created from and beyond them.

The popular pseudonymous crypto artist XCOPY, meanwhile, placed their iconic 1-of-1 NFT artwork “Right-click and Save As Guy” under the cc0 license in January, just one month after selling the piece. That cc0 designation has already resulted in a plethora of derivatives.

“Right-click Save As Guy” by XCOPY (1) / selection of derivative works based on the XCOPY original (2)

On Monday, XCOPY went even further, declaring an intention to go “all in” and apply cc0 to “all my existing art.” The artist added that “We haven’t really seen a cc0 summer yet, but I believe it’s coming…” – alluding to a possible period of growth akin to “DeFi summer” in 2020, when decentralized finance attracted a larger following.

… so I’m going to go ‘all in’ and apply CC0 all my existing art

— XCOPY(@XCOPYART) August 1, 2022

Why are so many NFT creators going down the “no rights” path?

One reason can be simply stated as doing it “for the culture” – promoting extensions of the original project, to bring out a more vibrant and engaged community. This can especially make sense in the context of crypto, where open sharing, and finding and building community, is part of the core philosophy for many.

Creative works live and die by their cultural relevance. And while NFTs may allow for provable ownership of any digital item, irrespective of licensing, cc0 also jumpstarts “meme–ability” by actively, not just passively, inviting the creation of derivative works. And as new derivatives are created and shared, attention can flow back towards the original, strengthening its place in the collective consciousness. This in turn may inspire even more interpretations, resulting in a flywheel effect whereby each additional derivative can add to the original’s value – akin to platform network effects, whereby platforms become more valuable to users as more users join them.

In other words, cc0 licensing lets creators more easily “seize the memes of production.”

“SEIZE THE MEMES OF PRODUCTION SEASON 1 – CARD 2“

Proliferation of cc0 throughout the digital landscape is just the start though – physical real-world products are leveraging cc0 NFT assets as well. The iconic square-framed glasses seen on each new NounsDAO NFT (tagline: “one per day, forever”) have been made into actual put-on-your-face, luxury sunglasses by the Nouns Vision project. Blitmap has seen their pixel-art freely depicted on shoes, clothing, and hats – all from different entities. This is in stark contrast to more traditional intellectual property models, in which a single owner would typically control that creation, licensing, and production.

The Blitmap Logo Hat is actually multiple cc0 levels deep: the physical “blitcap” (3rd level) is a derivative of the trait in the cc0 Chain Runners collection (2nd) that uses the “logo” original from cc0 Blitmap (1st)! The Logo is in fact Blitmap token #84, and is one of several in the Blitmap collection that has been used as a trait within other independent collections. (The “Dom Rose,” token #1, is another popular choice.) These homages allude to Blitmap’s influence as a cc0 leader, as one of the earliest major NFT projects to declare their public domain intentions. And the references continue to proliferate – for example, a new collection that launched last week, Citizens of Tajigen, included a version of the Blitcap trait.

These sorts of derivatives can be a win-win for all – not just for the original creators – especially for projects that are leveraging NFT assets to build novel brands: The derivative borrows some brand awareness from the source project; then, as people become independently aware of the derivative, that can drive new interest in the original. If you see someone wearing Nouns glasses on the street (or in a Super Bowl commercial), you might want to get a pair of your own – but you also might become interested in buying an original NounsDAO NFT or some other related derivative. [Indeed, the second author of this piece first found out about Blitmap by way of Chain Runners, and while Blits were way out of his range, he ended up acquiring a couple “Flipmap” derivatives.]

Physical Blitmap Logo Hat (1), Chain Runners #780 ft. Blitmap Hat trait (2) and the Blitmap Original “Logo #87” (3)

Open source as co-creation

The power of NFTs comes in part from the tech’s inherent composability, given that they are built upon smart contracttechnology. Many smart contracts are explicitly designed as building blocks, which can be combined or stacked upon one another to create ever richer applications.

The term “money Legos” was similarly coined to describe the combination of decentralized finance (“DeFi”) smart contracts interconnecting to form new financial use cases. (For example, the yield aggregator Yearn interacts withMakerDAO’s stablecoin $DAI and exchange liquidity provider Curve, among others, simply by calling public functions on their smart contracts.) Viewed through that same lens of composability, NFTs and their underlying smart contracts can act as the base-layer foundation upon which culture and creativity can recombine and interconnect.

And cc0 allows all of this to happen with the explicit permission of the original creators – thus giving an NFT’s enthusiast community a literal license to build new value layers whenever, wherever, and however they want.

Parallels can be drawn to open source more broadly – and in particular, to the rise of Linux. When the internet was still new, Microsoft controlled the majority of the operating system market with its closed-source operating system Windows. But Linux (and its creator Linus Torvalds) championed a community-first ethos, opening up the source code for all to use, modify, and distribute without restrictions. This (among other things) resulted in developers worldwide collaborating and creating new software for Linux – from web servers to databases and everything in between. As people (and companies) continued to create world-class open source software, Linux’s value proposition strengthened, ultimately leading to explosive growth and further innovation across the industry. According to market analyst Truelist, today Linux accounts for over 96.3% of the top 1 million web servers, as well as 85% of smartphones.

With cc0 licensing beginning to empower NFT community builders in a similar manner, one might hope for a long-term innovation trajectory here too. To build on a logic-Lego supplied by punk4156, a pseudonymous cofounder of NounsDAO: combining cc0 with NFTs “transforms an adversarial game into a co-operative one.” This is significant on a couple levels: First, decentralized systems from open source to crypto are about trust and coordination among strangers, so enabling cooperative opportunities is critical. Second, the dynamics of this cooperation work particularly well in the context of NFTs because giving people ownership over their digital assets enables them to internalize the results of the co-creation through the value that accrues to their assets and contributions – and that in turn incentivizes them to participate in co-creation in the first place.

Licensed to create

If cc0 projects are akin to individual open source “applications” or “platforms,” then the NFT artwork, metadata, and smart contracts provide the “user interface” – and the underlying blockchain (e.g., Ethereum) is the “operating system.” But for these applications to reach a Linux-like potential, more supporting infrastructure services need to be created and readily available so people can take maximum advantage of the remixing opportunities cc0 creates.

Those services are beginning to take shape. For example, the “hyperstructure” Zora protocol and OpenSea’s open sourceSeaport protocol enable open, permissionless marketplaces to be built for trading NFTs. Recently, a pixel-art-rendering engine was published entirely on-chain to the Ethereum blockchain, and it has already been integrated into projects such as OKPC and ICE64. Each successive application furthers the “out-of-the-box” blockchain capabilities, leading to new apps built up from those now more plentiful, enhanced building blocks.

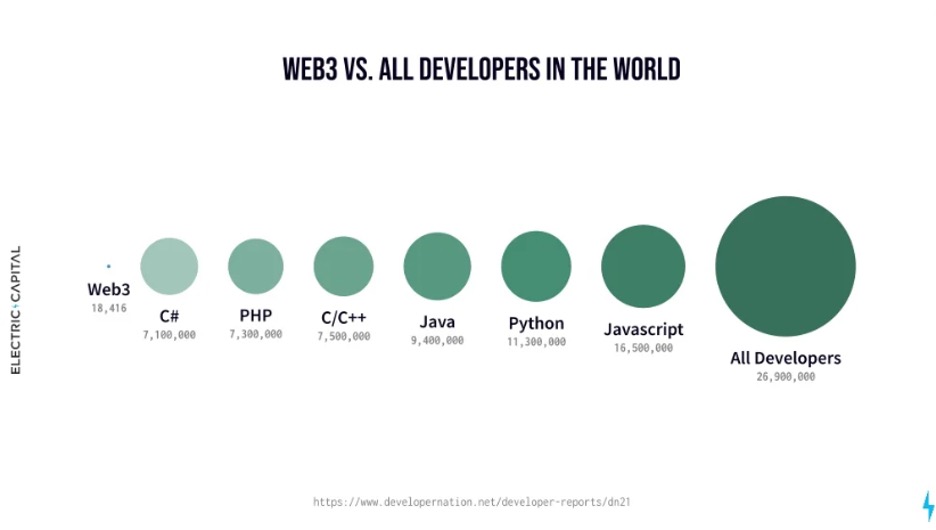

While web3 developer growth is at all-time highs and rapidly expanding, the total amount is still a small fraction of the total active software developers globally. But as more and more developers enter the space, aspiring NFT projects may find way more creative and infrastructure Legos to build upon, for cc0 projects and beyond.

Electric Capital Developer Report (2021), p. 122

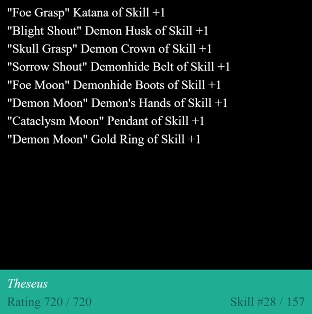

Composability is key to growth. With these digital assets built on public standards atop interoperable infrastructure, it’s easy for users to plug their assets into a variety of different platforms. An example of how such extensibility works in practice is the Loot Project, one of the first to show the evolution of decentralized co-creation, worldbuilding, and more in NFTs. We share this example also because it was notably low-fi or even “incomplete” aesthetically, leaving more space for imagination and more room for community co-creation.

For context, Loot started with a series of Loot bag NFTs, each comprising just a simple list of eight “adventure items” in white text on a black background (such as Loot Bag #5726’s “Katana, Divine Robe, Great Helm, Wool Sash, Divine Slippers, Chain Gloves, Amulet, Gold Ring”). Released for free by initial creator Dom Hofmann, these Loot bags served as a starting point for the community to build upon.

Several projects have indeed started fleshing out everything from metaphorical world-building (lore) to physical world-building (game development) in a short amount of time, with creators from all contributing many derivatives to the collective “Lootverse.” They’ve already made games (Realms & The Crypt); characters (Genesis Project, Hyperloot, andLoot Explorers); storytelling projects (Banners and OpenQuill); and even leveling infrastructure (The Rift).

How does cc0 and composability apply here? Because users own and control the foundational Loot bags – a primitive that makes sense in many different game and storytelling environments – they can use these core assets wherever they want, simply by connecting their crypto wallets. This allows them to participate in numerous derivative projects, including ones like Genesis Adventurers, whose special characters feature in many of the other projects – essentially enabling a decentralized franchise not owned by any one entity.

When to go cc0

As mentioned, there are many strategies NFT projects can take when it comes to developing and building their IP. When it comes to cc0, it’s important to be realistic. Simply applying the license isn’t going to magically turn any project into a sensation – you can’t expect the public domain to suddenly make something a beloved, runaway success. As with open source software, cc0 works best for NFT projects that create the potential for a rich, expanded ecosystem.

Many of the most successful cc0 projects to date have succeeded by introducing intellectual property that can be used flexibly across a range of different contexts. The Nouns brand is as intuitive for a beer ad as for physical glasses; Loot bags are basic primitives that make sense for all kinds of adventure settings; and the Goblintown art style looks as good on dwarves, zombies, and grumpy owls as it does on Val Kilmer.

We believe the ideal cc0 NFT project creates opportunities for builders to add value, both

- vertically, by stacking new content and features directly on top of the original cc0 assets (for instance, as with games built on the Loot ecosystem, among others), and

- horizontally, by introducing distinct but related intellectual property that helps propagate the original cc0 project’s brand (as with various Goblintown derivatives, among others).

The business model around cc0 NFT projects can benefit directly from these sorts of activities. Because cc0 NFT projects typically earn ongoing royalties from secondary sales, third-party expansions and derivatives can become sources of revenue by driving increased demand for the original cc0 assets.

Moreover, using cc0 licensing reduces friction that might otherwise stop brand-reinforcing extensions from being created – or worse, lead them to be created in a way that bypasses the original. As Robbie Broome recently explained (in the context of his cc0 project A Common Place), “By giving up my IP to cc0 rather than ‘protecting’ it, it avoids bad rehashes down the line. If, for example, UrbanOutfitters wanted to put my design on a tee, instead of hiring someone on their team to design something that looks like it, they can just use the actual work.” Sometimes, adopting cc0 can effectively turn competition into cooperation.

Additionally, cc0 projects can benefit significantly from community agreement about core assets’ value and contribution. Community cohesion and engagement is essential here. Building on the examples already mentioned above: While developers can, in principle, create adventure games around whatever themes and item concepts they want, the fact that many are choosing to develop around Loot bags reflects the community cohesion within the Lootverse. Meanwhile, Blitmap derivative project Flipmap shared part of their revenue with the original Blitmap artists in recognition of that project’s core position within the community – a move that can promote a healthy culture within a cc0 project ecosystem. As cc0 project commentator NiftyPins noted, “it was a smart move to honor the people who built the foundation for their universe to exist. It also fostered an environment where many of the OG Blitmap artists have been popping into the Flipmap discord and providing information and conversation.”

But again, cc0 isn’t a one-size fits all solution – NFTs built around brands that are already well-established, for example, might prefer to opt for far more restrictive licenses as a way of protecting their existing intellectual property and potentially reinforcing exclusivity. Moreover, while cc0 has some superficial similarity to the strategy of allowing NFT owners specifically to commercialize the intellectual property associated with the NFTs they hold – à la Bored Ape Yacht Club – there is a crucial difference: cc0 holders don’t have the right to exclude others from using the same IP. This can make it harder for holders to build commercial brands on top of the cc0 asset themselves or grant specific rights to partners – although holders can, of course, still introduce expanded intellectual property (such as backstories or derivatives) that they do completely control.

* * *

Decentralization and open development are core elements of blockchain technologies and the broader crypto ethos. This makes it very natural for crypto projects to build around cc0 content models – which build on the work of the Creative Commons foundation and several pioneers in open source – and may represent one of the purest formal embodiments of that open source philosophy to date.

As with the originators of open source software projects, NFT creators who opt for cc0 must decide how much of a role they want to play in assembling the surrounding ecosystem. Some cc0 project leaders, like the creators of Chain Runners, have continued building atop the initial cc0 assets themselves, actively establishing an environment that derivative projects can plug into and build on top of. Dom Hofmann, by contrast, stepped back from Loot, allowing the community to take charge. (That said, Dom is working on other cc0 NFT projects as part of the company he founded to develop Blitmap and more.) Other creators have opted out altogether, such as the recent case of the pseudonymous sartoshi, who announced his exit from the cc0 project he developed, mfers – and from the NFT space entirely – by releasing a final edition aptly named “end of sartoshi” and then deleting his Twitter account. The mfers project’s smart contract is now controlled by a multi-signature wallet of seven mfer community members.

Irrespective of the original creators’ level of ongoing engagement, cc0 licensing can enable a robust community to co-create in ways that provide value to all members. As the NFT space continues to evolve and mature, we expect to see more organized infrastructure and design patterns supporting these efforts. There’s also likely to be innovation around frameworks for value capture, just as there has been with open source software. (For example, we might envision a version of the “Sleepycat license,” which requires proprietary software products to pay licensing fees when they embed certain open source components.) And as creators continue to advance the space, we expect to see them develop, and experiment with, novel rights and licensing models far beyond what’s in use today. But in any event, cc0 offers a way for NFT creators to bootstrap projects that may one day take on a life of their own.

Flashrekt is a crypto enthusiast, NFT collector, and member of multiple DAOs including c0c0dao, a DAO that invests in cc0 projects, and SharkDAO, a NounsDAO-collecting club. Prior to his jpeg journey, he spent 15+ years in IT infrastructure.

Kominers is a Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, a Faculty Affiliate of the Harvard Department of Economics, and a Research Partner at a16z crypto.

Editors: Robert Hackett & Sonal Chokshi

***

Acknowledgments: Our thinking here reflects learnings from engaging with numerous NFT builders, theorists, and consumers, especially Robbie Broome, Christian Catalini, Chris Dixon, Jad Esber, Far, Jon Itzler, Li Jin, Valet Jones, Steve Kaczynski, Bharat Krymo, NiftyPins, SAFA, Margo Seltzer, Timshel, Jesse Walden, and the Chain Runners Architects. Special thanks also to our editor, Robert Hackett!

Disclosures: See full disclosures for a16z crypto and link to investments below; related to this article, the company and both authors hold NFTs, including some from collections mentioned in this piece. Flashrekt is also a member of DAO collecting clubs, and of a DAO that supports and invests in cc0 projects. Kominers advises a variety of marketplace businesses, startups, and crypto projects, and serves as an expert on NFT-related matters, including regarding questions related to intellectual property strategy; for further disclosures, see his website.

***

The views expressed here are those of the individual AH Capital Management, L.L.C. (“a16z”) personnel quoted and are not the views of a16z or its affiliates. Certain information contained in here has been obtained from third-party sources, including from portfolio companies of funds managed by a16z. While taken from sources believed to be reliable, a16z has not independently verified such information and makes no representations about the current or enduring accuracy of the information or its appropriateness for a given situation. In addition, this content may include third-party advertisements; a16z has not reviewed such advertisements and does not endorse any advertising content contained therein.

This content is provided for informational purposes only, and should not be relied upon as legal, business, investment, or tax advice. You should consult your own advisers as to those matters. References to any securities or digital assets are for illustrative purposes only, and do not constitute an investment recommendation or offer to provide investment advisory services. Furthermore, this content is not directed at nor intended for use by any investors or prospective investors, and may not under any circumstances be relied upon when making a decision to invest in any fund managed by a16z. (An offering to invest in an a16z fund will be made only by the private placement memorandum, subscription agreement, and other relevant documentation of any such fund and should be read in their entirety.) Any investments or portfolio companies mentioned, referred to, or described are not representative of all investments in vehicles managed by a16z, and there can be no assurance that the investments will be profitable or that other investments made in the future will have similar characteristics or results. A list of investments made by funds managed by Andreessen Horowitz (excluding investments for which the issuer has not provided permission for a16z to disclose publicly as well as unannounced investments in publicly traded digital assets) is available at https://a16z.com/investments/.

Charts and graphs provided within are for informational purposes solely and should not be relied upon when making any investment decision. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The content speaks only as of the date indicated. Any projections, estimates, forecasts, targets, prospects, and/or opinions expressed in these materials are subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by others. Please see https://a16z.com/disclosures for additional important information.