There has been a lot of buzz about “the metaverse” since its coinage in the ‘90s, but especially during the pandemic (given the surge in online activity), and even more so after Facebook changed its name to Meta.

Is this just a bit of opaque marketing-speak? What is a metaverse exactly? How does one define the term, and where does one draw a line between a metaverse and, say, just another virtual world? These are common questions that people ask about the metaverse, so we thought we’d outline how we see it and how the metaverse intersects with web3.

In many ways, the metaverse is just another name for evolving the internet: to be more social, immersive, and far more economically sophisticated than what exists today. There are, broadly speaking, two competing visions for how to bring this about: One is decentralized, generous with property rights and new frontiers, interoperable, open, and owned by the communities that build and maintain it. The other vision — too familiar to many people today — is centralized, closed, subject to the whims of corporations; and often extracts painful economic rents from its creators, contributors, and inhabitants.

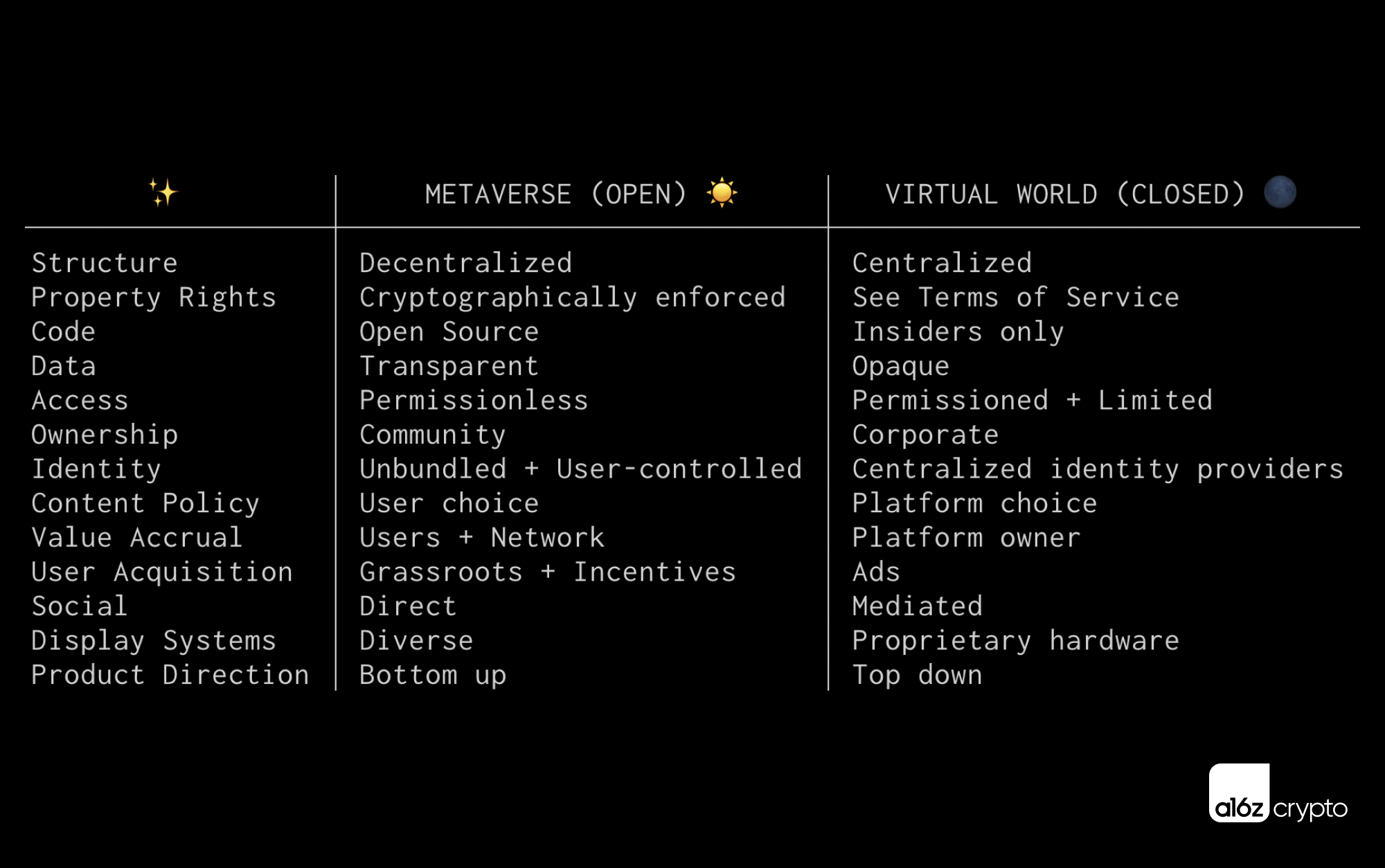

The key dimension to compare these two visions is open vs closed, and the differences between them can be conceptualized as follows:

An open metaverse is decentralized, allows users to control identity, enforces property rights, aligns incentives, and ensures value accrues to users (not platforms). An open metaverse is also transparent, permissionless, interoperable, and composable (others can freely build within and across metaverses), among other criteria.

Achieving a “true” metaverse — one that’s open versus closed — requires seven essential ingredients intrinsic to this sought-after state. We argue that these are necessary to meet the minimum requirement to be called a metaverse. Our goal is to clear the fog of misinformation about what is and isn’t a true metaverse for builders and would-be participants, and to provide a framework for evaluating early metaverse attempts.

1. Decentralization

Decentralization is the overarching, governing principle of a proper metaverse, and many of the traits that follow depend on or result from this main concept.

By decentralization, we mean not owned or operated by a single entity or at the mercy of a few powerbrokers. Centralized platforms tend to start friendly and cooperative to attract users and developers, but once growth slows they become competitive, extractive, and zero-sum in their relationships. Often these powerful intermediaries engage in user rights abuses and de-platforming, and they host captive economies with aggressive take-rates. Decentralized systems, on the other hand, exhibit more equitable ownership among stakeholders, reduced censorship, and greater diversity.

Decentralization matters. Without it, anyone can get “rugged” at any time — a precarious situation that dissuades people from building on top, hampering innovation. Because centralized platforms cannot make the same kinds of strong commitments — controlled by code — that blockchains can, their promises can be revoked or altered whenever an arrangement no longer makes sense to the whims of leaders or organizations. The strongest way to protect against such abuses and secure a metaverse is to ensure that control is decentralized.

2. Property rights

Most successful video games today make money by selling in-game items, like “skins”, “emotes”, and other digital goods. But people who currently buy in-game items aren’t actually buying items – they’re renting them. As soon as anyone leaves for a different game — or the game in question unilaterally decides to shut down or switch up the rules — players lose access.

People have grown so accustomed to renting from the centralized services of web2 that the idea of actually owning things — digital objects you can sell, trade, or take elsewhere — often strikes people as odd. But the digital world ought to obey the same logic as the physical world: when you buy something, you own it. It’s yours. Just as courts of law uphold these rights in the physical world, so should code enforce it online. It just so happens that true digital property rights weren’t possible before the advent of cryptography, blockchain technology, and related innovations such as NFTs. Put simply, metaverses turn digital serfs into homesteaders.

3. Self-sovereign identity

Identity is closely related to property rights. You can’t own anything if you don’t own yourself. As in the real world, people’s identities must be able to persist throughout the metaverse without complete reliance on a small set of centralized identity providers.

Authentication is about identity: proving who a person is, what they have access to, and what information they share. On the web today, this requires asking an intermediary to do so on one’s behalf with popular one-click login methods like social login or single sign-on (SSO). Today’s biggest tech platforms, like Meta and Google, use this approach to collect data to build their businesses: monitoring people’s behavior to develop models that serve more relevant ads. In addition, because these platforms have complete control, trying to innovate on the authentication process relies on the honesty and willingness of the corporation behind the platform.

The cryptography at the core of web3 enables people to authenticate without relying on these intermediaries, so people can control their identity directly or with the help of services they choose. Wallets (like Metamask and Phantom) provide ways for people to verify themselves. Standards like EIP-4361 (Sign-in with Ethereum) and ENS (Ethereum Name Service) allow projects to coordinate around open source protocols and contribute independently to a richer, more secure, and continually evolving concept of digital identity.

4. Composability

Composability is a systems design principle, and here specifically it’s the ability to mix and match software components like lego bricks. Every software component only needs to be written once, and can thereafter simply be reused. It’s analogous to compounding interest in finance or Moore’s law in computing — some of the most powerful known economic forces — because of the exponential power it can unlock.

To feature composability — a concept closely intertwined with interoperability — a metaverse would have to offer high quality, and open, technical standards as a foundation. In games like Minecraft and Roblox, you can build digital goods and new experiences out of the basic components supplied by the system, but it’s harder to move them outside that context or modify their inner workings. Companies offering embeddable services, like Stripe for payments or Twilio for communications, work across websites and apps — but they don’t allow outside developers to change or remix their black boxes of code.

In their strongest form, composability and interoperability are possible permissionessly across wide ranges of the software stack. Decentralized finance, or DeFi, exemplifies this strong form. Anyone can adapt, recycle, change, or import existing code. Not only that, developers can build on live programs — such as Compound’s lending protocols or Uniswap’s automated market-making exchanges — at their leisure, side-by-side in the memory of a shared virtual computer (Ethereum). By composing together powerful new ingredients like property rights, identity, and ownership, builders can create completely new experiences.

5. Openness/open source

True composability is impossible in the absence of open source, which is the practice of making code freely available and able to be redistributed and modified at will. Regardless of degree or kind, open source as a principle is so essential to the development of a metaverse, that we’ve broken it out as its own separate ingredient despite the overlap with composability above.

So what does open source mean in a metaverse development context? The best programmers and creators — not the platforms — need full control to be fully innovative. Open source, and openness, helps ensure this. When codebases, algorithms, marketplaces, and protocols are transparent public goods, builders can pursue the fullness of their visions and ambitions to build more sophisticated, trustable experiences.

Openness leads to more secure software, makes the economic terms more knowable to all parties, and eliminates information asymmetries. These properties can create fairer, more equitable systems that actually align network participants. They could also even obviate the need for outdated U.S. securities laws, which were designed decades ago to reconcile the longstanding principal-agent problem and information asymmetries in business.

The power of composability in web3 is largely due to its open source ethos.

6. Community ownership

In a metaverse, all stakeholders should have a say, proportionally to their involvement, in the governance of the system. People should not just have to abide by the edicts passed down by a group of product managers at a tech company. If any one entity owns or controls this virtual world, then much like Disney World, it may offer a certain form of contained escapism but will never live up to its true potential

. Community ownership is the piece of the puzzle that aligns network participants — builders, creators, investors, and users — to cooperate and strive for a common good. This miracle of coordination — previously unwieldy or not possible without the advent of crypto and blockchains — is orchestrated through the ownership of tokens, the native assets of networks.

Beyond the technological advancements created by decentralization, the philosophical implications of a community-owned space is crucial to the success of the metaverse. Across web3, participants in decentralized autonomous organizations, or DAOs, have taken this principle to heart. They are eschewing the formal rigidity of corporate structures in favor of more flexible, more varied democratic, and informal experiments in governance. This allows for communities that are governed, built, and driven forward by their users, rather than by a single entity.

7. Social immersion

Big tech companies would have you believe that high-powered virtual reality or augmented reality (VR/AR) hardware is an essential — perhaps even the most essential — ingredient in a metaverse. This is because those devices are a trojan horse. Corporations see them as a way to becoming the dominant computing interface suppliers for 3D virtual worlds, and thereby also becoming the choke points that intermediate people’s metaverse experiences.

A metaverse does not have to exist in VR/AR. All that’s necessary for a metaverse to exist is social immersion in the broad sense. What’s more important than hardware is the type of activities metaverses enable. They will let people remotely hang out, work together, mingle with friends, and have fun, much like they do using Discord, Twitter Spaces, or Clubhouse today.

,p>The pandemic underscored the need for more immersive experiences — beyond traditional text based communication platforms, such as email — as the use of other remote conferencing and telepresence tools, like Zoom and others, soared. Further, because of the economic elements outlined earlier — property rights, self-sovereignty, community ownership — metaverses can enable people to make a living, engage in business, and attain status. In a typical knowledge worker’s workplace, people collaborate using tools like Slack, while outside the traditional corporate world in the bottom-up organizational movement of DAOs, Discord and Telegram prevail.

The metaverse has nothing to do with “view” modalities — the tools you use to see the metaverse. That’s a convenient meme for those who have control over manufacturing hardware.

***

While a number of companies have begun building out different pieces of the whole, if a virtual world is lacking in any of the above parts, it doesn’t count as a fully formed metaverse, in our view. We believe — as is evident in this framework — that a metaverse cannot exist without the fundamental foundations of web3 tech.

Openness and decentralization are the pillars upon which the whole edifice rests. Property rights rely on decentralization — they must endure despite the influence of powerful adversaries. Community ownership prevents unilateral control of the system. The approach also bolsters open standards, which are helpful for decentralizing and composability, a closely related property downstream of interoperability.

The development of an ideal multi-dimensional virtual world will come about gradually. Many problems remain to be solved, lest we wind up with some dystopian analogue of the IOI-mediated Oasis in Ready Player One. If builders stick to these axioms, though, that outcome will be less likely. (If you’re such a problem-solver or builder, get in touch with us!)

When the metaverse arrives, it should embody a full expression of these principles — with decentralization at the core.

Thank you to Robert Hackett for his editing of this piece.